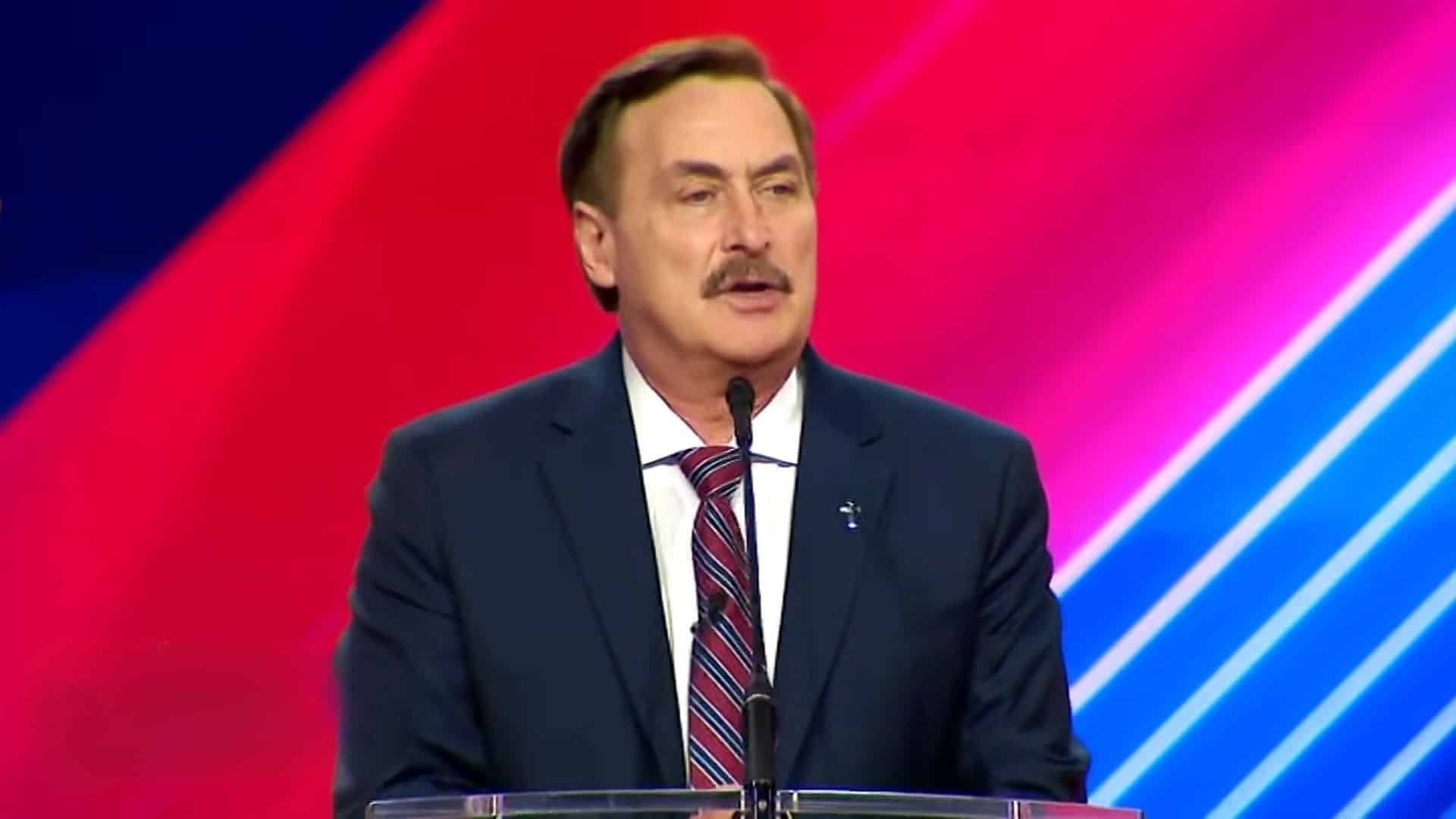

Campaign finance records reveal that Mike Lindell’s gubernatorial campaign has allocated a significant portion of its funds, over half of the approximately $356,000 raised, to purchasing his own self-published book, “What Are the Odds?”. These book purchases, totaling around $187,000, were made to Lindell’s for-profit company and represent an unusual campaign expense compared to other candidates. This spending has drawn criticism and legal scrutiny, particularly in light of ongoing legal battles related to election fraud claims and outstanding legal fees.

Read the original article here

It appears that the financial dealings of Mike Lindell, the founder of MyPillow, have once again landed him in the spotlight, and this time it’s about how his campaign funds were allegedly spent. The core of the discussion revolves around a substantial portion of his campaign money being used to purchase his own book, raising questions about the intent and transparency of these expenditures.

The narrative suggests a pattern where political figures, particularly within the MAGA sphere, might be engaging in questionable financial practices that resemble a “grift” or a “political money laundering scheme.” The idea that Lindell might have spent a significant chunk of his campaign funds on his own literary efforts is presented not as an isolated incident but as a potential continuation of a tactic employed by others.

One might wonder about the specific mechanics of such an arrangement. The input hints at possibilities like a tax write-off or a way to generate personal income through royalties and kickbacks, suggesting a less than straightforward financial maneuver. This raises the pertinent question of who exactly donated the substantial sums – $356,000 is mentioned – to Lindell’s campaign, and what their expectations were regarding how their contributions would be utilized.

The way this money was allegedly used, purchasing his own book, is seen by some as a way to essentially wash campaign funds into his own pockets. This action is being compared to other instances where political committees or individuals have been accused of using campaign money for personal benefit, or to artificially boost the sales of their own products.

The practice of buying large quantities of one’s own book to achieve bestseller status, or simply to move inventory, is brought up. While not entirely new, with examples of publishers and authors doing this, the context of campaign funds makes it particularly problematic. The input points out that simply buying the books is one thing, but failing to then sell them at a reasonable price, thereby recouping the money for the campaign or donating them, is where the alleged impropriety lies.

There’s a cynical observation that this practice might be contagious within certain political circles, with an analogy drawn to Kid Rock allegedly buying his own music and the Church of Scientology’s bulk purchases of L. Ron Hubbard books to keep them in print. This paints a picture of a self-serving ecosystem where campaign funds are diverted to prop up personal ventures.

The input also touches on Lindell’s broader platform and campaign promises. These include restoring the original flag, banning Sharia law, addressing bathroom policies, and lowering various taxes. While these are presented as campaign planks, the context of his alleged financial dealings casts a shadow, making some question the sincerity of his motivations and the effectiveness of his campaign strategies.

The notion of embezzlement, or at least something akin to it with “extra steps,” is put forth as a potential description of Lindell’s alleged actions. The idea that campaign funds, meant for political campaigning, are being redirected for personal gain, especially in light of past accusations of him bankrupting his company and owing millions to lawyers, adds a layer of skepticism.

Comparisons are drawn to other political figures who have faced similar scrutiny. Bernie Sanders, for instance, is mentioned as having spent a considerable amount of campaign money on his books, with a subsequent purchase of a lake house. Sarah Palin also faced criticism for similar financial maneuvers in 2007. This suggests that while Lindell’s actions might be particularly egregious in the eyes of some commentators, the underlying tactic isn’t entirely unprecedented.

However, the input also acknowledges that this type of financial activity isn’t exclusive to one political party, describing it as “bipartisan scumbaggery.” This broader perspective suggests that the issue of campaign finance and the potential for self-enrichment is a systemic problem that transcends specific political affiliations.

Ultimately, the core of the commentary is that spending the majority of campaign funds on one’s own book, especially when the campaign itself is perceived as a “grift” or a vehicle for personal gain, is highly questionable. It leaves many wondering about the true intentions behind the campaign and the ethical implications of such financial decisions, particularly for those who donated in good faith.