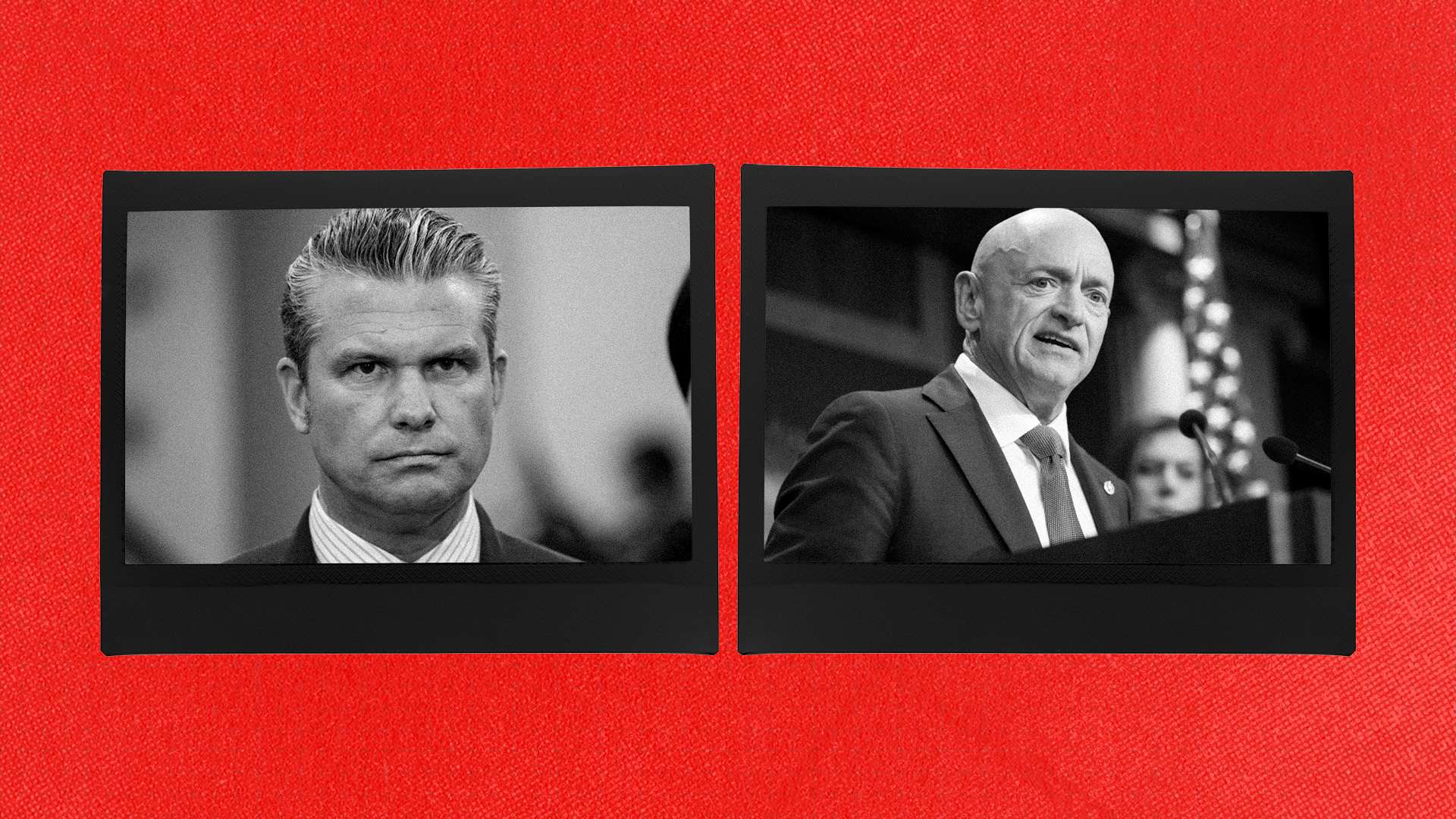

U.S. District Judge Richard J. Leon has ruled that Senator Mark Kelly’s statements to military personnel about refusing illegal orders are protected by the First Amendment. The judge granted Kelly a preliminary injunction against Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, barring penalties based on comments Hegseth deemed prejudicial to good order and discipline. Leon concluded that Kelly was likely to prevail in his claim that Hegseth retaliated against his constitutionally protected speech, a principle he found inapplicable to retired service members, especially those serving in Congress. The ruling clarifies that while active-duty military members have restricted speech rights, retired members, particularly legislators performing oversight, are entitled to full First Amendment protections.

Read the original article here

A federal judge has recently clarified a fundamental aspect of American governance that seems to have eluded some: a president cannot jail legislators simply because a video they produced has offended him. This ruling serves as a stark reminder that in the United States, the power to imprison is reserved for those who break established laws, not for those who cause hurt feelings or bruise egos. It’s a concept that one might expect to be understood at a much younger age, and it’s rather astonishing that it requires a judicial pronouncement.

The idea that there could be some kind of legal loophole allowing for the jailing of individuals for expressing dissent, even if it comes in the form of a video, is patently absurd. Such actions are not illegal. At their core, these protections are rooted in the First Amendment of the Constitution, a cornerstone of American liberty that guarantees freedom of speech and expression. It appears that this foundational principle needs continuous re-explanation, particularly to those who seem to operate under the assumption that their personal sensibilities dictate the law.

This situation highlights a crucial distinction between a president and a monarch. While some may harbor delusions of absolute power, the President of the United States is bound by the Constitution and the rule of law, not by personal whim or the desire to silence critics. Legislators, in their official capacity, have a duty to represent their constituents and to speak out on matters of public concern, even if their actions or words displease the current occupant of the White House. To suggest otherwise is to fundamentally misunderstand the principles of representative democracy.

The notion that truth-telling or performing one’s duty by informing the public about potentially unlawful or harmful actions constitutes a crime is, frankly, only conceivable within a very narrow and partisan mindset. The broader legal and societal consensus is that such actions are not only permissible but often necessary for a healthy democracy. The president’s own often-repeated complaints about unfair media treatment seem to stem from a similar confusion, where any reporting that doesn’t align with his desired narrative is perceived as an attack.

One can only hope that such fundamental legal concepts are explained in a manner that is easily digestible, perhaps even visually, for those who struggle with them. The idea that a judge’s intervention is necessary to explain that the First Amendment remains in effect even when someone’s feelings are hurt underscores a concerning disconnect from basic civic understanding. It’s not just a matter of free speech; it’s also about the separation of powers, a core tenet of the U.S. legal system. The Constitution clearly delineates the roles and responsibilities of different branches of government, and the president does not have the authority to overstep these boundaries to punish political opponents.

The legal challenges faced by past administrations, including numerous unsuccessful lawsuits aimed at overturning election results, demonstrate a pattern of behavior that disregards established legal processes and outcomes. Judges, even those appointed by the president himself, have consistently rebuked such frivolous challenges. This pattern reinforces the idea that the president is not above the law and cannot simply invent crimes to silence his critics. The Founders themselves were deeply concerned with protecting citizens from arbitrary power, and they designed a system of checks and balances specifically to prevent such abuses.

Ultimately, the principle is straightforward: the law is designed to govern conduct, not to regulate emotions. While a president might feel personally offended by a piece of political commentary, that offense does not translate into a legal basis for imprisonment. The Constitution protects speech, even speech that is critical or disagreeable, because a free exchange of ideas is essential for a functioning democracy. To suggest otherwise is to advocate for a system where power supersedes principles, a path that America’s founders actively sought to prevent. The judge’s explanation, however basic it may seem, serves as a vital reaffirmation of these enduring constitutional values.