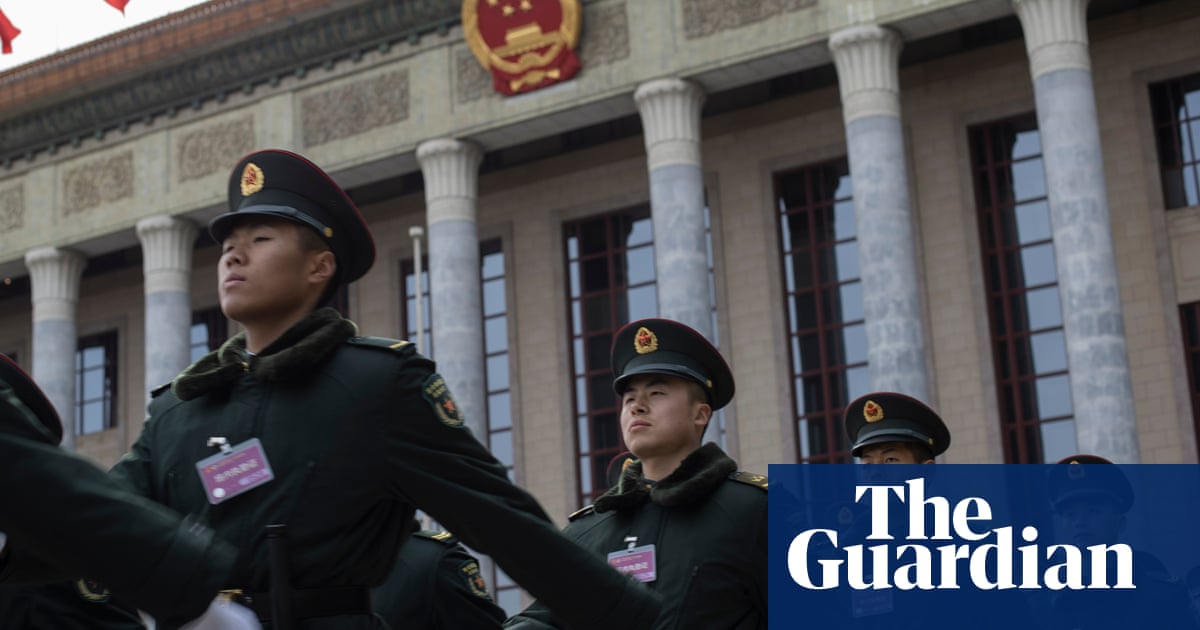

New research from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) reveals China’s nuclear warhead stockpile is expanding at an unprecedented rate, adding approximately 100 warheads annually since 2023, reaching at least 600. This rapid growth, driven by Xi Jinping’s leadership, contrasts with previous policies emphasizing modest deterrence. At this pace, China could possess nearly 1,500 warheads by 2035, approaching the readily deployable arsenals of Russia and the U.S., prompting concerns particularly for Taiwan. The report concludes that the post-Cold War era of nuclear weapons reduction is ending.

Read the original article here

China’s rapid expansion of its nuclear arsenal is raising significant global concerns. For decades, the commonly held belief was that a stockpile of around 300 nuclear warheads, in various configurations, provided sufficient deterrence for national defense. The massive arsenals possessed by the US and Russia were largely attributed to Cold War paranoia and the imperative to eliminate any possibility of a successful first strike. This is why many other nuclear states maintain a similar range of 200-300 weapons.

China’s escalating nuclear build-up, however, suggests a different dynamic. It could indicate a perception that the US and/or Russia are becoming increasingly aggressive, necessitating a stronger deterrent to counter potential attacks. History, unfortunately, shows that nuclear powers can act with impunity against non-nuclear states, further fueling the incentive for countries to acquire their own nuclear capabilities.

The perceived failure of the security guarantees offered to Ukraine in exchange for its nuclear weapons, inherited from the USSR, has created a chilling effect. The lesson seems to be that national sovereignty is best secured through the possession of nuclear weapons. Any nation choosing not to pursue this path might be considered unwise in the current geopolitical climate. The potential success of the US’s Golden Dome missile defense system is also a concern, as it could disrupt the existing balance of nuclear deterrence, potentially leading China to build up its own arsenal as a countermeasure.

The global situation is undeniably volatile. While some may express greater trust in China’s actions compared to the US, the reality is that the expansion of nuclear arsenals by any nation is deeply troubling. The anxieties surrounding potential future conflicts, including the possibility of a war in Taiwan, only exacerbate this concern. It is impossible to ignore the massive destructive potential of even a limited number of nuclear weapons; one weapon is practically indistinguishable from 50 in terms of the catastrophic consequences of their use.

The argument that the military-industrial complex is driving this arms race is certainly plausible. The sheer number of nuclear weapons already in existence, enough to destroy the world many times over, makes further expansion seem illogical. However, the reality is more complex. The Cold War arms race was primarily about quantity and size, a competition for supremacy. The situation with Taiwan is different; it is about the willingness of China to accept losses to achieve its strategic goals.

The current geopolitical climate appears to mark the end of the post-World War II peace. The US’s ambition to enhance its missile defense systems could be interpreted as a challenge to existing nuclear deterrence. The idea of achieving a 90%+ shoot down rate on incoming missiles, however, only raises the stakes and necessitates an even larger nuclear arsenal for effective retaliation. The underlying issue is a dangerous increase in global tensions fueled by a desire for more power and resources rather than contentment with the already immense wealth and power possessed by many nations.

The question of who would control a potential EU nuclear arsenal, and how countries with anti-nuclear stances would react, raises significant political hurdles. Furthermore, the assumption that a nuclear attack on one EU country would trigger an automatic retaliatory strike from all others is unrealistic. Even if the EU were to obtain ICBMs, the financial and political challenges are monumental. The EU’s current military capabilities are insufficient to defend Ukraine effectively even with US support, making a significant increase in defense spending unlikely. A nation’s decision to develop nuclear weapons is a high stakes gamble; North Korea, protected by China, and Israel, protected by the US, managed to get away with it. Iran, without such protection, faces far more serious consequences.

The principle of mutually assured destruction (MAD) is widely considered an effective deterrent; however, advocating for all nations to acquire nuclear weapons is a dangerously pro-nuclear stance. While the benefits of a robust defense against invasion are undeniable, the potential consequences of nuclear war outweigh any other consideration. China’s measured approach of minimum deterrence, coupled with a public no-first-use policy, offers a seemingly more rational approach than the policies of many other nuclear powers. Yet, the situation remains precarious, leaving the world teetering on the brink of unthinkable catastrophe.