Yale University has suspended computer science professor David Gelernter from teaching while it reviews his conduct after newly released documents showed he described a student as a “v small good-looking blonde” in an email to Jeffrey Epstein. Gelernter defended his description by stating he was mindful of Epstein’s “habits” and believed he did not dishonor the student, adding that her intelligence and beauty were relevant information for a potential employer. Students were notified of his suspension and Gelernter later claimed the university’s action was based on a private email dug from Epstein’s files.

Read the original article here

The revelation that a Yale professor, David Gelernter, recommended a “good-looking blonde” student for a job with Jeffrey Epstein, and subsequently expressed no regret, has ignited a firestorm of public reaction. The core of the controversy lies in Gelernter’s candid admission that he was aware of Epstein’s problematic predilections and factored them into his recommendation, while simultaneously defending his actions as a matter of not suppressing relevant information.

Gelernter’s rationale, as reported, was that Epstein, like many wealthy and unmarried men, was “obsessed with girls.” He explicitly stated that he was keeping “the potential boss’s habits in mind” and, as long as he didn’t “dishonor her in any conceivable way,” he would provide the information he thought the recipient wanted. He described the student as “smart, charming & gorgeous” and unequivocally declared, “Ought I to have suppressed that info? Never!” Furthermore, he added, “I’m very glad I wrote the note,” a statement that has been widely interpreted as a complete lack of remorse.

This unrepentant stance has drawn considerable criticism, with many finding it astonishing that a tenured professor would respond to such serious allegations with such a dismissive attitude. The suggestion that people shouldn’t read publicly available emails, particularly when those emails involve potentially facilitating harm, has been met with incredulity. It’s argued that individuals involved in such circumstances forfeit any claim to privacy or common courtesy, especially when their actions could be construed as complicity.

The act of cc-ing the student newspaper on his response to Epstein, described as a “Fuck Off note,” has further amplified the sense of defiance and, for some, a foreboding premonition of consequences. Given his age, the professor’s apparent indifference to potential repercussions suggests he may believe he has little to lose. This calculated brazenness has led some to correctly identify him even before his name was revealed, based on his known history and perceived disposition.

The academic and professional background of Gelernter, a distinguished figure in parallel computation, dating back to the 1980s, makes this revelation even more jarring. His prior work, including the Linda programming system named after Linda Lovelace, a figure from adult film, adds a layer of complexity, perhaps hinting at a long-standing disregard for conventional sensitivities. However, this historical context does little to mitigate the current outrage over his recommendation.

The email in question, sent in October 2011, several years after Epstein’s guilty plea for soliciting prostitution from an underage girl, directly showcases Gelernter’s disturbing perspective. Describing the candidate as an “editoress” and “v small good-looking blonde” in a recommendation for a job with Epstein, a man known for his predatory behavior, paints a picture of profound insensitivity and a troubling understanding of women. Critics argue that this language reveals an uneducated and backward view of women, as problematic as Epstein’s sexual predation.

This incident, alongside other notorious associations within elite academic circles, fuels a broader concern about the values and behaviors perpetuated within institutions like Yale. The comparison to the “Tiger Mom” incident and the general sentiment that being a female academic can be a difficult experience underscore the pervasive nature of such biases. The idea of bragging about recommending someone, especially to a figure like Epstein, is seen as not only disgusting but remarkably foolish.

The sentiment that some individuals, including Gelernter, operate with a sense of entitlement and a belief that they understand the world’s hierarchy better than others is a recurring theme. The notion that “good-looking cattle are trophies” and that professors like Gelernter merely explain this grim reality, highlights a deep-seated cynicism about power dynamics and social stratification. The core question remains: how could anyone in a position of authority not feel remorse for potentially pushing a young student into a dangerous environment?

The argument that these individuals are not sorry for their actions but rather for getting caught or exposed is a stark and cynical perspective. The distinction between genuine remorse and regret over exposure is crucial. Gelernter’s statement, “I’m very glad I wrote the note,” seems to confirm this cynical view, suggesting a lack of true contrition. Even if he were to issue a statement of regret, it’s perceived as likely to be a performative gesture rather than a genuine expression of sorrow.

The context of Epstein’s circle, where individuals sought out science intellectuals but also benefited from immense wealth and connections, creates a complex web of motivations. It’s suggested that people may not be sorry for accepting Epstein’s money or connections, regardless of his personal conduct. This perspective posits a world driven by self-interest, where ethical considerations take a backseat to personal gain.

This perception aligns with a broader critique of Ivy League institutions, often described as bastions of greed, narcissism, and an inflated sense of superiority. The idea that these institutions have historically perpetuated harmful practices and that the people within them are complicit in these actions suggests a deeply ingrained problem. The more Gelernter speaks, the more his position appears untenable and his views problematic.

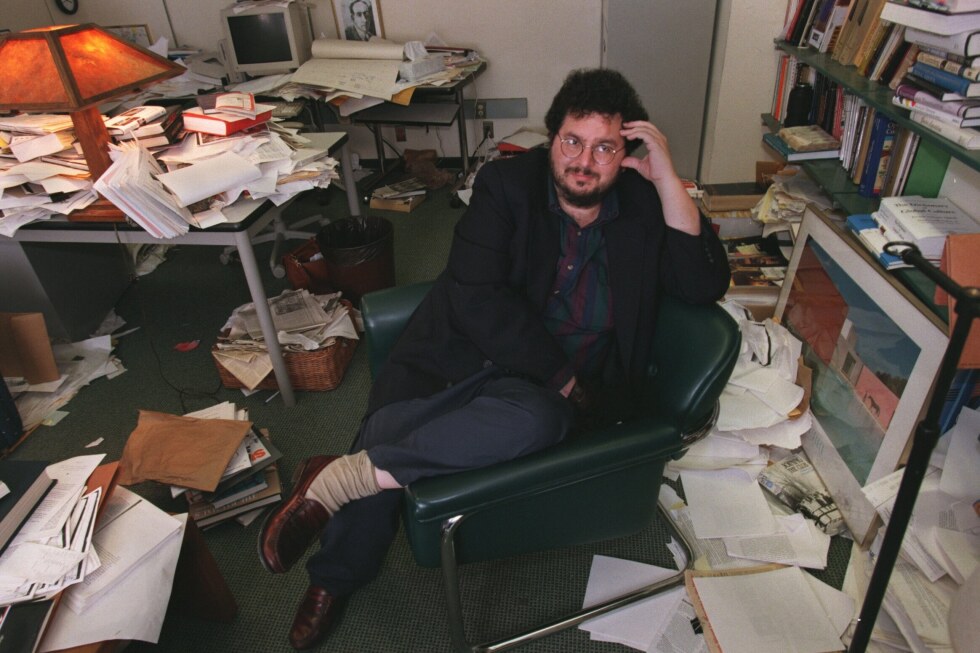

The description of his office as a “mess” and the comparison to an episode of “Hoarders” further paints a picture of disarray and a lack of professional integrity. The fact that this same professor was a target of the Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski, adds an ironic and grim historical footnote to the current controversy, raising questions about what Kaczynski, a figure who railed against modern technological society, might have understood about the underlying issues.

The notion that Yale is a “scumbag factory” and that such behavior contributes to the perpetuation of harmful systems is a powerful indictment. The incident also touches upon the ongoing debate around diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives, with some suggesting that while DEI is meant to address bias, this type of behavior is precisely what it aims to call out. The unacknowledged biases of those in privileged positions, their tendency to elevate those like themselves, and their casual disregard for the harm they cause, are all facets of this complex issue.

The lack of fear or shame displayed by those in positions of power, who seem to believe they are above accountability, paints a picture of a dystopian reality where consequences are negligible. The desperate plea for the professor to simply show some remorse and self-awareness underscores the public’s expectation of ethical conduct, an expectation that seems to have been entirely disregarded in this instance.

The question of accountability looms large. Will Gelernter face consequences for his actions? Will he be removed from his position? The apparent lack of immediate repercussions fuels a sense of disillusionment, suggesting that little will change and that such institutions may continue to employ individuals who enable harmful behavior. The implication that Yale is complicit in grooming future leaders with such problematic individuals is a grave accusation.

The observation about the chaos within his office and the historical pattern of “monsters” emerging from elite universities like Harvard and Yale suggests a systemic issue that might necessitate a fundamental curriculum change. The suggestion that Ivy League schools are merely “nepotistic social centers” rather than bastions of academic excellence is a cynical but increasingly resonant viewpoint, especially as more troubling associations come to light. The fact that the Unabomber almost succeeded in assassinating him, and that he now recommends students to Epstein, leads some to ponder what the Unabomber truly understood about certain societal elements. The phrase “United States of Rapestein” highlights the widespread impact of Epstein’s crimes and the perceived complicity of those who facilitated his activities.

The visceral reaction, including wishes for physical harm, underscores the depth of anger and disgust. The description of his appearance as a “neckbeard nest” and “pig” reveals the personal attacks that often accompany such public outrages. The theory that men who only promote women based on their attractiveness likely do so because that’s the only criterion they themselves are judged by is a cynical but not entirely unfounded observation about patriarchal power structures. The parallel between Gelernter and Epstein, both being white men who allegedly engaged in exploitative behavior, further fuels these criticisms. The notion that tenured professors can be “lunatics with helicopter blades as moral compass” points to the perceived disconnect between academic power and ethical responsibility.

Ultimately, the incident with David Gelernter and the “good-looking blonde” student serves as a stark reminder of the enduring issues of bias, entitlement, and complicity within privileged circles. The lack of remorse expressed by Gelernter is not just a personal failing but a symptom of a broader systemic problem that demands serious introspection and, for many, significant change. The question of accountability, and whether genuine remorse will ever emerge from such situations, remains unanswered.