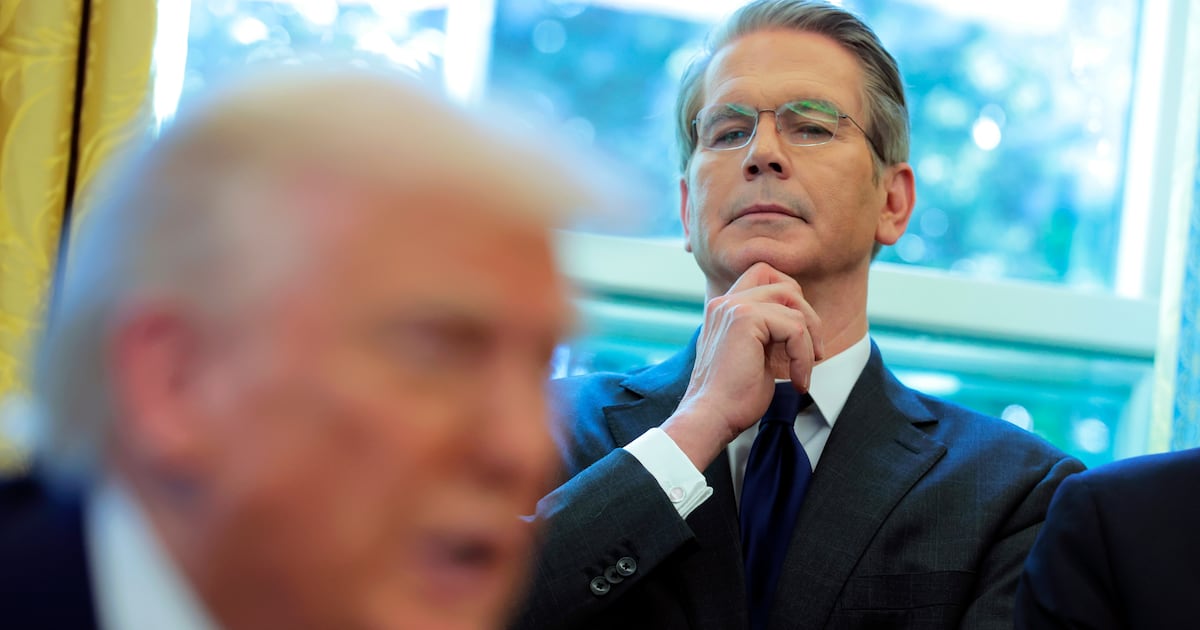

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent expressed optimism that Americans will not receive billions collected from tariffs, following a Supreme Court ruling that declared their imposition unlawful. The Court’s decision leaves the fate of these collected funds uncertain, with a dissenting justice noting the potential for a “mess” regarding refunds. Bessent previously walked back the president’s pledge of a tariff dividend, suggesting refunds would amount to “corporate welfare,” as reports indicate tariff costs have largely been passed to U.S. consumers and businesses. This comes amidst economic challenges for Americans and the president’s proposal of new across-the-board tariffs.

Read the original article here

It appears there’s quite a bit of frustration boiling over regarding tariffs imposed during the Trump administration and the subsequent handling of collected funds. The core of the issue seems to revolve around a perceived injustice where consumers bore the brunt of tariff costs, only for companies to potentially benefit from refunds while consumers see no relief.

Let’s break down this sentiment: Trump’s Treasury officials, or as some colorfully put it, “goons,” are being accused of a rather dismissive attitude towards returning money collected through tariffs. The underlying problem, as many see it, is that when tariffs were implemented, businesses didn’t absorb the costs themselves. Instead, they shrewdly passed those increased import expenses directly onto consumers by raising prices on goods.

So, the sequence of events as understood by many is quite galling. Tariffs are announced and applied. Companies import goods, pay the tariffs, and then, crucially, increase their prices to compensate. This means the average person, the consumer, ends up paying more for everyday items. Then, when legal challenges deem these tariffs unlawful, and the Supreme Court (or similar rulings) dictates they should be returned, the initial expectation is that this refund would somehow trickle down or offset the costs consumers already paid.

However, the emerging narrative suggests something entirely different. Companies, who had already recouped their tariff payments by charging higher prices to consumers, are now in line to receive refunds for those very tariffs. This is where the feeling of being “screwed” really intensifies for the public. Not only did they pay more for goods, but the money collected through unlawful tariffs, which was intended to be refunded, is now potentially going back to the businesses that already profited from the price hikes.

The concern is that this creates a perverse incentive. Companies are effectively rewarded for passing on costs, and then further benefit because consumers are already accustomed to the higher prices. There’s little expectation that these businesses will spontaneously lower their prices once they receive tariff refunds, meaning the higher prices become the new normal, leaving consumers perpetually at a disadvantage.

This situation leads to a broader question being voiced: is it ever truly possible for the average American to come out ahead under policies enacted during that period? The feeling is that the nation is being “sacked,” with financial gains benefiting a select few while the general population bears the burden. Some even suggest that states should consider class-action lawsuits to reclaim money that was effectively taken from working people through these tariff-driven price increases.

There’s also a sense that the justifications for these tariffs, and the subsequent revenue collected, are being obscured. Some comments allude to a broader economic strategy where tariffs served as a means to finance other initiatives, perhaps even tax cuts for the wealthy, a point that fuels further resentment. The disconnect between the declared intent of tariffs and the actual outcome for consumers is a significant source of anger.

The alleged dismissiveness from Treasury officials regarding these refunds is particularly irksome. The promise, or at least the implication, was that if tariffs were found to be unlawful, the collected revenue would be handled appropriately, which many interpreted as meaning refunds to those who ultimately paid. The current stance, suggesting no refunds for consumers and potentially only to the companies, is seen as a betrayal of that understanding, and a clear instance of “lawlessness” and “chaos.”

It’s notable that some of the criticism points to a perceived lack of memory among supporters of these policies, who perhaps don’t recall promises made about tariff refunds. The argument being made is that while the government indirectly collected money from consumers via these tariffs, that money isn’t being returned to the consumers who paid it, but rather to the companies that acted as intermediaries in the government’s collection process. This then sets up a potential future scapegoat, where the administration could blame the companies for the price hikes, deflecting responsibility.

The “sneering” mentioned in the title isn’t just about a facial expression; it represents an attitude of contempt or derision towards the very people affected by these policies. It suggests a lack of empathy and a disdain for the financial struggles of ordinary citizens. The accusation is that the entire administration operated with this sort of condescending air, believing themselves to be above reproach and the law.

The contrast between past assurances and present actions is a key point of contention. There are mentions of court filings where the administration stated they would refund tariffs plus interest if they were deemed unlawful. The current reluctance to do so directly contradicts these previous statements, leading to accusations of duplicity and a willingness to ignore court orders if it suits their agenda.

Essentially, the collected tariff revenue is seen as having already been “pocketed” or “stolen.” The argument is that by the time any ruling demanding refunds comes into effect, the money has been dispersed or allocated in ways that make full restitution to consumers practically impossible.

This leads to a yearning for accountability, with some questioning if civil class-action lawsuits against former officials are even possible to address the financial damage caused. The underlying belief for many is that these tariffs were a thinly veiled tax on consumers, designed to benefit specific interests rather than the broader public good. The perceived refusal to return the collected funds is interpreted as a confirmation of this exploitative intent.

The “greedy narcissist” label applied to Trump reflects a belief that he views the collected tariff money as personal property, rather than government revenue. This perspective suggests a fundamental misunderstanding of public office and a self-serving approach to governance. The idea is that he would fight to keep the money simply because he feels entitled to it, regardless of legal or ethical considerations.

The entire situation is framed by some as a betrayal by those who voted for such policies, especially when considering groups that ostensibly champion minimal government intervention and oppose taxation. The irony of these groups supporting policies that resulted in what’s perceived as theft is highlighted. The “First rule of acquisition” – never give back money once you have it – is invoked as a cynical summary of the perceived modus operandi.

Ultimately, the sentiment expressed is one of deep dissatisfaction and a feeling of systemic unfairness. The “Treasury Goon sneers at handing back tariff loot” captures the essence of this frustration: a perception that those in power are not only indifferent to the financial hardships they’ve imposed but are actively resistant to rectifying their mistakes, leaving the public to bear the cost while the beneficiaries of their policies face no repercussions.