The recent release of documents pertaining to Jeffrey Epstein’s investigation has revealed the pervasive influence and interconnectedness of the wealthy elite, exposing their shared tolerance for his depravity despite differing political affiliations. This coterie of plutocrats, including figures like Bill Gates, Peter Thiel, and Elon Musk, now engage in a public blame game as their association with Epstein comes under scrutiny, highlighting a disturbing pattern of wealth and power shielding individuals from accountability. Epstein’s own correspondence suggests a cynical worldview, thriving on global upheaval and societal instability for personal profit, a mindset echoed by the article’s assertion that the ruling class is inherently “rotten to the core” and poses a threat to democracy. This situation prompts a debate, exemplified by Senator Bernie Sanders’ critique of an elite class above the law versus pundits like Matt Yglesias who advocate for “billionaire positivity,” arguing that their contributions to business and philanthropy outweigh their perceived moral failings.

Read the original article here

It’s becoming increasingly hard to look at the highest echelons of our society without feeling a deep sense of unease, and frankly, disgust. The scandals that periodically erupt, like the Jeffrey Epstein affair, don’t just reveal isolated incidents of depravity; they feel like windows into a deeply corrupted system, a ruling class that is, to put it bluntly, rotten to the core.

The Epstein scandal, in particular, has laid bare how wealth and influence can create a shield, protecting individuals from accountability that ordinary citizens can only dream of. It feels less like an anomaly and more like a symptom of a pervasive rot, where the wealthy and powerful operate with a sense of impunity, shielded by their connections and vast resources. The notion of a few “bad apples” seems disingenuous when the evidence suggests an entire orchard of compromised individuals.

This isn’t a new phenomenon; the history of the so-called “robber barons” of the 19th century is rife with tales of similar entitlement and exploitation. The pursuit of wealth and power often seems to come at the cost of basic human decency, suggesting that a certain level of sociopathy might even be a prerequisite for climbing to the very top. Privilege, when unchecked by accountability, breeds a profound disconnect from the realities faced by the majority.

The intersection of money, power, and misogyny, as highlighted by the revelations surrounding Epstein’s circle, paints a disturbing picture. It suggests that for some within this elite group, the exploitation and objectification of others, particularly women, is not just a byproduct of their lifestyle but perhaps an ingrained element of their worldview, a way to maintain control and reinforce their perceived superiority.

When we see how the American government itself can be perceived as compromised, with suggestions of pedophilia and glorification of those connected to such scandals, the sense of disillusionment deepens. While in other countries, individuals associated with figures like Epstein are rightly condemned, here, the narrative feels murky, protected by layers of influence and obfuscation.

The idea of taxing the extremely wealthy or subjecting them to severe legal consequences, even as a stark choice, arises from a growing frustration with perceived injustice. It speaks to a desire for retribution and a fundamental rebalancing of power, where those who have benefited disproportionately from societal structures are held to account.

The term “ruling class” itself can feel like a euphemism for organized crime, operating with a veneer of legitimacy thanks to sophisticated public relations, private jets, and a legal system that often seems to favor their interests. Public apathy, fueled by distraction and a feeling of powerlessness, allows this system to persist.

Therefore, a crucial step seems to be recognizing who comprises this “ruling class” and actively divesting from the systems that enrich them and grant them further leverage. This might involve conscious choices about consumption, support for businesses and platforms that disproportionately benefit these individuals, and a general withdrawal of complicity.

The names that surface in these discussions, from tech moguls to influential figures, often reveal a network of interconnected individuals who may have benefited from or been aware of unsavory dealings. The deliberate omission of certain names from investigations or discussions can be particularly maddening, fueling the suspicion that the system is designed to protect its own.

The call for impeachment or severe legal penalties against those implicated underscores the public’s desire for decisive action. When revelations expose such deep-seated corruption, it can feel like a collective descent into madness, a desperate plea for sanity and justice.

The feeling that “lot of dots are beginning to connect” can quickly morph into the understanding that it’s not a series of isolated incidents but “one big blot,” a systemic issue that has always been present. This realization is both terrifying and, in its own way, clarifying.

The concept of proscription, of actively removing these individuals and their influence from positions of power and wealth, emerges as a radical but perhaps necessary response. Ideas of redistributing wealth and ensuring that individuals are comfortable but not in a position to further exploit society reflect a desire for a more equitable world.

The notion of a “global diet,” a collective effort to curb the excesses of the ultra-wealthy, speaks to a widespread yearning for a more balanced distribution of resources and power. It’s about recognizing that the unchecked accumulation of wealth by a few often comes at the expense of the many.

The argument that oligarchs are “fully deranged” and operate with a level of amorality that allows them to engage in serious transgressions as a means of blackmail and control suggests a chilling logic to their cohesion. This shared vulnerability, born from their illicit activities, might be the very glue that binds them together.

The idea that governments are unwilling or unable to dismantle these power structures because they are intrinsically linked to them is a recurring and unsettling theme. It points to the conclusion that the impetus for change must come from the people themselves, a grassroots movement to reclaim agency and dismantle oppressive systems.

For those who have witnessed this pattern repeatedly, the sentiment of “First time?” can feel like a weary observation, a nod to the cyclical nature of power and corruption that has been evident throughout history, from the French peasants of the 18th century to the present day.

The question of “What can one do?” becomes paramount. Simple acts of mindful consumption, like reducing reliance on certain tech giants or platforms, can feel like small but significant gestures of resistance. These actions, when multiplied, can have a tangible impact and signal a collective refusal to participate in systems that perpetuate inequality.

The belief that amassing immense wealth inherently signifies a “horrible person” is gaining traction, driven by the observation that such accumulation often stems from a prioritization of money, power, and control over empathy and genuine benefit to society. The idea that billionaires aren’t working for the common good but solely for their own advancement resonates deeply.

It’s also argued that the elite actively work to distract from the fundamental issue of class struggle, creating divisions and focusing public attention on trivial matters while the concentration of wealth continues unabated. The notion that there is enough wealth for everyone, yet it is hoarded by a select few, fuels this discontent.

There’s a compelling argument that a deep-seated genetic or psychological inclination towards coveting money above all else leads to a deficit in fundamental human qualities like compassion and kindness. Observing individuals who seem unmoved by suffering and perhaps even derive pleasure from it, especially when linked to political affiliations that seem to benefit such interests, reinforces this unsettling perspective.

The corrupting influence of absolute power, a theme explored in fiction and now seemingly realized in reality, suggests that the detached, self-serving characters we once dismissed as caricatures might, in fact, be disturbingly true to life. This unchecked power, wielded by those who disdain the majority, has become a palpable force.

History consistently shows that power corrupts, and the best we can hope for is to limit the time individuals spend in power and actively fight against the corruption that inevitably arises. This historical perspective offers little comfort but underscores the need for continuous vigilance and resistance.

The association of the Republican Party with protecting wealthy child predators, and the comparison between Epstein’s island and Bezos’ rocket, highlights a perceived continuity in the behavior and networks of the elite, regardless of their political affiliations. The idea that they are all participating in a high-stakes game of “Survivor: Wealth Edition” with the resources of the common people is a stark and cynical observation.

The provocative assertion that “Every billionaire is a rapist until proven otherwise” stems from a deep-seated suspicion that the accumulation of such immense wealth, particularly through certain industries and practices, is inherently tied to exploitation and a disregard for human well-being.

The disillusionment with political parties, seen as serving power-hungry individuals with sociopathic tendencies, leads to a call for greater accountability. The stark contrast between the taxes paid by CEOs and the burden on ordinary citizens, while the former flaunt their wealth, fuels this sense of injustice.

The role of algorithms and media in distracting and polarizing the public with “insignificant bullshit” is seen as a deliberate tactic to maintain the status quo. This manufactured distraction allows the elite to operate with less scrutiny and public resistance.

The comparison of Epstein’s island to Bezos’ rocket, both representing the ultimate indulgence of the ultra-rich, and the assertion that they are all “pedos and pharaohs playing hunger games with our rent money,” encapsulates a profound anger and sense of exploitation.

The specific mention of tax relief for billionaires, even for endeavors like discovery and development, raises questions about whether these actions are genuine contributions or merely sophisticated tax write-offs designed to further enrich those already at the top.

The observation that in leaked documents, only victims’ names are redacted, while influential figures are not, suggests a deliberate effort to protect the powerful and expose the vulnerable. The sheer volume of such documents and the conversations within them point to a deeply ingrained culture of complicity and questionable behavior.

The description of the elite as “fueled by greed and empty inside” and a reflection of a timeless, perhaps even biological, “lust” for life that is expected and inevitable, paints a bleak picture. The question, “Now what?” arises from this sense of existential challenge.

While some hope that “the kids will be okay,” implying a generational shift towards greater awareness and responsibility, the immediate reality of entrenched power structures and the seemingly unchangeable nature of some individuals at the top remains a daunting prospect.

The foundational principles of some societies, it is argued, were designed to protect property from the majority, and this remains the underlying structure of power. This requires an explicit and intentional counter-effort to challenge the implicit power held by the elite.

The observation that this particular online forum has shifted towards a more critical and progressive stance is noted, suggesting a growing awareness and a collective desire for change.

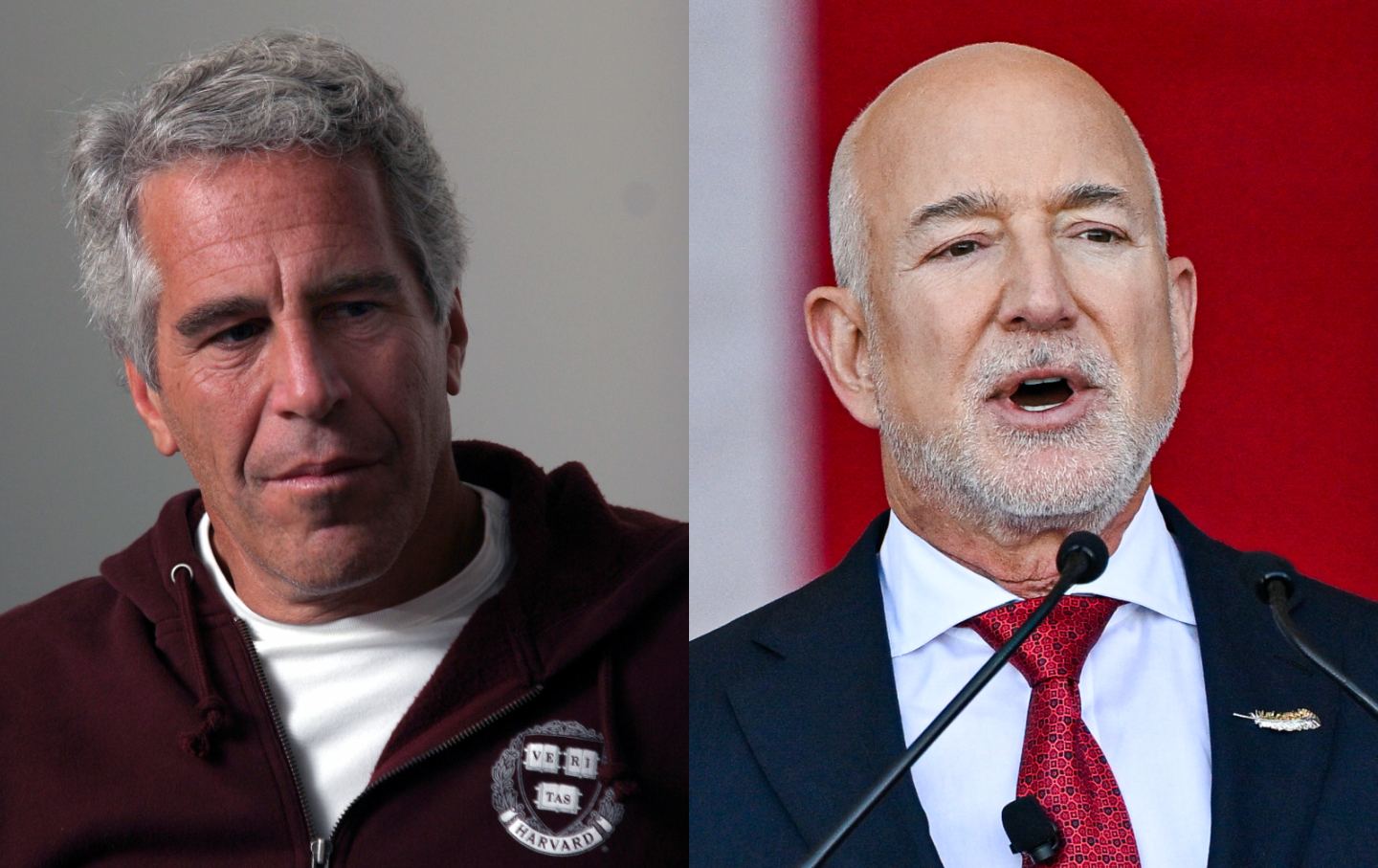

The inclusion of Jeff Bezos in the initial framing, despite not being directly implicated in the Epstein scandal, points to a broader critique of the billionaire class and their perceived impact on society, raising questions about the article’s focus.

The suggestion to rename the “ruling class” the “Epstein class” is a potent indicator of how deeply this scandal has permeated public consciousness and its association with systemic corruption.

The reference to the TV show *Mr. Robot* and its depiction of rich psychopaths playing God without permission highlights how fiction has often mirrored and perhaps even anticipated the societal anxieties surrounding unchecked power and wealth. The longing for a real-world “F society” underscores a desire for a collective force that can challenge these seemingly insurmountable power structures.