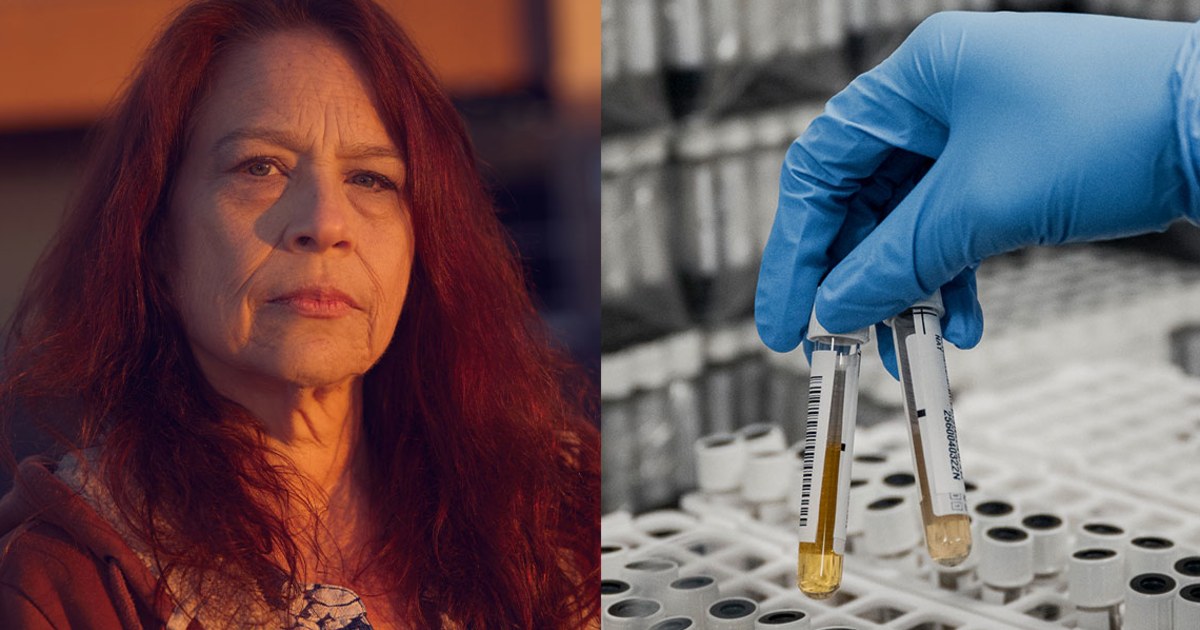

In suburban strip malls and towns across the country, a growing number of Americans are selling their plasma for compensation, an increasingly vital source of income to cover basic expenses. This practice, occurring at over 1,200 plasma centers, has seen a significant rise as individuals, even those with stable jobs and marketable skills, struggle to keep up with rising costs. The multibillion-dollar industry provides an estimated $4.7 billion annually to donors, highlighting a critical financial lifeline for middle-class households facing economic precarity.

Read the original article here

The notion of middle-class Americans resorting to selling their plasma to make ends meet is a stark indicator of shifting economic realities, suggesting that the traditional definition of the middle class may be increasingly out of reach for many. It’s a practice that, for some, has become a necessity to cover basic expenses, even for those who might be earning what was once considered a comfortable income. This situation prompts a reevaluation of who truly constitutes the “middle class” when such measures are being taken.

The act of selling plasma itself raises questions about economic stability. For individuals to be in a position where they need to monetize a part of their body, even for a relatively common biological substance, implies a level of financial precariousness that contradicts the historical understanding of middle-class security. The idea of a “golden age” where such activities are commonplace feels incongruous with the image of a thriving middle class.

Many express skepticism about labeling those who sell plasma as middle class. It’s argued that if one is dependent on receiving payment for their bodily fluids to cover everyday costs, they are no longer truly operating within the middle-class bracket. Instead, they might be better described as the “working poor” or having slid into a new category of economic hardship.

Reflecting on past experiences, some recall donating plasma in college towns a decade or more ago. Back then, while there was always a consistent line, it seemed to comprise a significant number of individuals experiencing homelessness rather than students. The compensation, though modest and capped by frequency, was a tangible amount for those in need, with initial donations often fetching a slightly higher rate.

The physical experience of donating plasma could also be inconsistent. Some technicians were adept, leading to quick and painless procedures, while others struggled, resulting in bruising and discomfort. This variability, coupled with the compensation, eventually led some to discontinue the practice, finding it too frustrating for the financial return.

In contrast, donating blood is now often preferred by some for its simplicity and the accompanying small rewards, like a cookie and juice. Blood donation experiences are frequently described as more straightforward, with less difficulty in finding veins. This comparison highlights a potential difference in the perceived value and logistics of donating blood versus plasma.

The pervasiveness of plasma donation advertisements, particularly on social media algorithms, is also noted. Seeing these ads can be a jarring experience, leading to an uncomfortable self-assessment of one’s financial standing, and sometimes, an unsettling confirmation that the algorithm’s perception of one’s financial state is accurate.

The disconnect between economic indicators, like a soaring stock market, and the reality of people selling their plasma is a significant point of contention. It fuels disbelief in claims of a strong economy when such desperate measures are visible. The perception is that this practice is not a sign of a robust economy, but rather its opposite.

The visibility of diverse demographics in plasma donation lines, such as a noticeable increase in young white individuals in areas like Brooklyn, is interpreted as a clear signal of economic downturn. It suggests that the financial strain is no longer confined to specific groups but is affecting a broader spectrum of the population.

The decision to forgo certain discretionary spending, like daily coffee shop visits, is cited as another way individuals are attempting to manage their finances. This practical adjustment, while seemingly minor, underscores the pressure to find additional funds when income isn’t stretching as far as it used to.

Ultimately, the consensus among many is that selling plasma is incompatible with being middle class. If one needs to engage in such a practice to survive, it fundamentally alters their economic classification. The middle class, as traditionally understood, implies a level of financial security that doesn’t necessitate selling one’s bodily resources.

However, it’s important to acknowledge the profound gratitude expressed by some for plasma donors. For individuals who have relied on plasma-derived medical treatments, donors are seen as lifesavers, highlighting the critical role these donations play in healthcare. There’s a strong sentiment that this contribution should be recognized without shame.

Some observers propose a starker view of societal stratification, suggesting that the concept of a middle class has largely dissolved. They posit that society is now divided into an elite, or “pedobillionaire class,” and a manipulated working population, often referred to as “worker bees,” who are expected to endure difficult circumstances.

The discussion often circles back to the idea that there simply isn’t a middle class anymore. This perspective suggests a fundamental shift in economic structure, where the traditional buffer between the wealthy and the poor has eroded.

There’s a poignant plea not to disparage plasma donation, recognizing its essential nature for many. The act itself is framed as a vital contribution, underscoring the life-saving potential of plasma.

The current political climate is also implicated by some, with accusations that specific administrations have created or exacerbated economic conditions that necessitate plasma donation. This viewpoint attributes the rise of this practice to policy decisions and funding cuts, particularly in areas like cancer research.

The significant profits generated by physicians and hospitals from plasma and other biological materials, contrasted with the relatively low compensation for donors, is a point of ethical concern. It highlights a perceived imbalance where the providers profit immensely from resources that are contributed by individuals who receive meager payment.

The question is persistently asked: if people are selling their plasma, can they truly be considered middle class? This rhetorical question encapsulates the core of the debate, emphasizing that such an action is a strong indicator of financial distress.

The dynamic where the top economic strata ascend while others remain stagnant is seen as a fundamental reason for this decline. When the overall economic pie grows, but an individual’s slice doesn’t, they are effectively falling behind, even if their income appears the same on paper.

The focus on political choices and the influence of large corporations is another thread in the conversation. Some believe that electing candidates favored by major corporations has led to economic policies that benefit the wealthy, with little positive impact trickling down to the average person.

An illustrative example is provided of a couple earning $120,000 annually in Idaho who are selling plasma to manage car payments and unexpected expenses like tires and medical bills. This scenario challenges the notion that only low-income individuals are participating in plasma donation.

Conversely, some argue that a $120,000 income should be sufficient to live comfortably without resorting to plasma sales. This perspective suggests that lifestyle choices and spending habits, rather than solely income levels, might be contributing factors to financial struggles, pointing to a tendency to live beyond one’s means.

The sentiment that there is no longer a “middle class” is frequently reiterated, replaced by a more polarized economic landscape. The concept of middle-class security is seen as an illusion for many.

Personal accounts of fatigue and visible marks on the arm from frequent donations are shared, offering a glimpse into the physical toll of this practice. These experiences reinforce the idea that it’s not a simple, consequence-free activity.

The assertion that selling plasma automatically disqualifies one from being middle class is a strong and commonly held belief. It signifies a threshold of financial necessity that defines a different economic stratum.

Some believe that those selling plasma are now considered lower-middle class and are on a downward trajectory towards poverty. The rising cost of living coupled with stagnant wages creates a precarious situation where gross income can quickly fall below the effective poverty line.

The act of selling parts of one’s body is seen by some as aligning more with poverty or sex work than with middle-class existence. This stark comparison highlights the perceived severity of the economic circumstances.

Speculative theories, such as the idea of billionaires requiring large amounts of plasma for obscure future plans, add a layer of dark humor or commentary to the discussion. These ideas, while perhaps outlandish, reflect a deep distrust and unease about the concentration of wealth and power.

The statement that if one is selling plasma, the middle class “no longer exists” is a powerful declaration of economic change. It suggests a fundamental alteration in the social fabric, where the traditional middle ground has disappeared.

For some, donating plasma is a deliberate choice for supplemental income. Earning $70 twice a week, totaling $560 a month, is described as a significant financial boost that helps considerably. This perspective frames plasma donation as a side hustle that allows for productive use of downtime, such as catching up on shows or reading.

This approach to earning extra money through plasma donation is presented as a practical solution, a way to augment a full-time job’s income without requiring extensive physical labor or specialized skills. It’s seen as a manageable addition to one’s financial resources.

The idea that if you are selling plasma, you are simply poor, not middle class, is a blunt but recurring assessment. It directly challenges the possibility of a middle-class individual engaging in this practice.

In Canada, the situation is different, with plasma sales being prohibited. This leads to regular shortages and appeals for donations, while simultaneously restricting certain individuals from donating based on factors like sexual orientation. This exclusionary practice is seen as counterproductive, given the constant need for blood and plasma.

The frustration of being a universal donor with a healthy body, yet being denied the opportunity to contribute due to arbitrary regulations, is a point of contention for some. It highlights a perceived inefficiency and unfairness in the donation system.

For others, plasma donation is a lucrative side hustle, yielding $200 extra per week for about two hours of their time. This is framed as an opportunity for quiet reflection or engaging in personal interests before starting their main workday.

The significant earnings potential of plasma donation, sometimes amounting to thousands of dollars over a year, is acknowledged. This suggests that for some, it’s a strategic financial decision, not just a desperate measure.

The stark contrast between the low compensation for donors and the high profits for medical institutions is a recurring theme. It raises ethical questions about who truly benefits from the donation process.

The core question of whether plasma donors are indeed middle class is repeatedly posed, highlighting the central debate. The act itself seems to be the definitive marker of economic status.

The observation that as the top economic performers advance, others, who remain stationary, are effectively falling backward is a powerful metaphor for economic inequality. This “holding still” is a form of regression when compared to the progress of others.

The influence of voting for candidates perceived to favor large corporations is seen as a direct contributor to economic policies that benefit the wealthy. The promise of “trickle-down economics” is met with cynicism.

The idea that professions in a “decadent empire” might include being a “blood boy” to a billionaire reflects a critique of societal values and economic opportunities. It suggests a decline in traditional career paths and a rise in less conventional, potentially exploitative, forms of income generation.

The statement that people have been doing this “forever” suggests that plasma donation for income might not be a new phenomenon, but rather a persistent, though perhaps increasingly visible, aspect of economic survival.

The long-term financial gains from consistent plasma donation, accumulating to significant sums over time, are noted. This suggests that for some, it’s a sustained effort to build financial reserves.