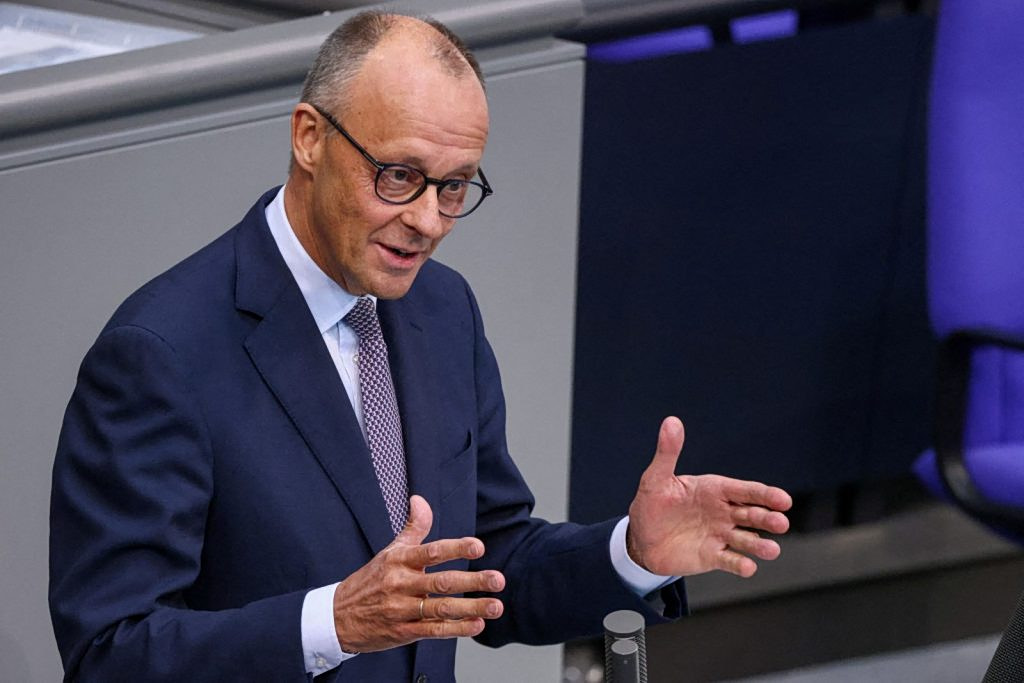

Friedrich Merz has urged Germans to work longer and harder, citing limited working hours and high sick leave as detrimental to economic growth. He pointed to Greece, which has a longer average working week, as a model for increased productivity. However, Merz faces domestic opposition and limited political power to enact significant labor reforms, as Germany grapples with rising unemployment and declining industrial output.

Read the original article here

It appears that some prominent figures are calling for a significant increase in the workload for Germans, with a rather surprising and arguably ironic example being presented: Greece. This suggestion to work more, and to do so by emulating the economic situation in Greece, has understandably sparked considerable discourse and, frankly, a good deal of bewilderment. The sentiment often expressed is one of profound exhaustion. Decades of being told that the solution to economic woes lies in simply working harder and making further sacrifices, with promises of a better future just around the corner, have evidently worn many people down. This feeling of being perpetually on a treadmill that’s only speeding up, while the promised finish line remains elusive, is a recurring theme.

The choice of Greece as a model for increased productivity is particularly noteworthy, given how vociferously they were criticized and pressured just a few years ago due to their substantial debt. This stark reversal in narrative raises questions about the sincerity and consistency of such pronouncements. It leads some to feel that they are being subjected to a form of gaslighting, where pronouncements from those in positions of wealth and power seem to disregard the lived experiences of the majority. The immediate reaction for many upon hearing such calls is not motivation, but rather a disinclination to work even harder, with some even contemplating disengaging from work altogether.

There’s a strong argument to be made that the concept of “productivity” itself needs to be re-examined. What does it truly mean to be productive, and for whose benefit? When one considers the vast overproduction of goods, from clothing to food, that often end up being discarded due to market logistics or a lack of demand, it becomes clear that our current systems are not aligned with genuine human or planetary needs. The sheer abundance of wealth that exists, which could theoretically foster a world akin to a Star Trek utopia, is instead concentrated in the hands of a select few, leading to a sense of deep dissatisfaction and a desire for fundamental change.

This dissatisfaction manifests as a call to dismantle and challenge the prevailing economic paradigms with the same vigor that some perceive as being used to oppress ordinary citizens. The idea of working more is often interpreted as a refusal by elites to implement fairer taxation policies or to address wealth inequality directly. Instead, the burden is shifted onto the working population, under the guise of needing a “better work ethic” or the necessity to “compete with other major powers.” This perspective suggests a mindset rooted in outdated, neo-liberal economic theories, perhaps influenced by an era where running a state like a business was seen as the ultimate solution, rather than focusing on people’s well-being.

Furthermore, the notion of supporting local employers is sometimes seen as a way to prop up inefficient or failing businesses, favoring an oligarchical structure over genuine free-market principles. This type of thinking is perceived by some as a throwback to 1990s economics, lacking any forward-looking vision and actively hindering progress. The feeling of being constantly told that Germans are lazy or too frequently ill, by individuals who themselves may not truly understand the meaning of hard work or the daily grind, is deeply demoralizing. For those already working at full capacity, the message to “work more” offers no incentive and instead feels like a personal discouragement.

The comparison to Greece’s economic situation, where the shift towards multiple part-time jobs is often a necessity for survival rather than a choice for flexibility, highlights a potential future that is far from comfortable or peaceful. In Northern Europe, part-time work is traditionally viewed differently, often associated with student life or a specific phase of education. The current rhetoric, however, suggests a departure from this, implying that increased work, often under less secure conditions, is the expected norm, while corporate elites continue to reap the majority of the benefits. This disparity is what fuels the desire to work less.

This situation is increasingly seen as a catalyst for a global reckoning against the prevailing oligarchy. The individuals making these pronouncements are sometimes identified as having backgrounds in finance, which may explain their inclination to view economic challenges through a lens of maximizing output and profit, regardless of the human cost. The idea that working “smarter” is superseded by a simplistic demand to “work harder” is considered outmoded. Many believe that true productivity stems from strategic planning, process optimization, technological adoption, investment in employee training and well-being, and fostering a positive work environment that prioritizes work-life balance, not from simply exhausting the workforce.

The core issue, as many see it, is a lack of genuine incentive for increased effort. If individuals are expected to work more, it should be met with tangible rewards, such as increased wages, which would enable them to afford basic necessities like housing. The current approach, where the burden is placed on workers while the fruits of their labor are disproportionately enjoyed by others, is viewed as a sign that new leadership is needed. This is particularly true when the narrative seems to suggest that the collective prosperity is tied to the economic struggles of another nation, creating a sense of deep irony, especially given historical perceptions.

The suggestion that Germany should look to Greece as a model for increased work is a headline that many could not have envisioned even a decade ago, given the past criticisms. The idea that politicians might wish for Germans to work 24/7 until they drop dead is a concerning sentiment, and the parallel with calls to reduce public holidays for productivity reasons further emphasizes the perceived devaluation of workers’ time and well-being. It is argued that instead of encouraging businesses to invest more, which could genuinely boost economic performance and move the country away from the bottom of global investment rankings, the blame is conveniently placed on the workers.

There is also the chilling prospect that increased work is simply a means to accelerate the adoption of automation, leading to job displacement. The current economic trajectory is seen by some as the endpoint of unchecked capitalism, where the sole objective is the accumulation of wealth by a tiny fraction of the population. The failure to recognize the systemic issues, such as geopolitical entanglements and industrial dependencies, and instead to focus on individual workers’ behaviors, such as taking sick days, is considered a misguided and potentially damaging strategy. The question of whether individual efforts would translate into tangible benefits, like Volkswagen finding billions, remains unanswered.

Ultimately, the sentiment is that those who advocate for working more should perhaps experience the reality of sustained hard labor themselves to truly understand the challenges faced by the average worker. The notion that free-market principles and modern economics are inherently clear is challenged when the proposed solutions seem to ignore basic principles of incentivization and equitable distribution of gains. The suggestion that simply increasing wages could lead to greater effort and economic activity is dismissed as a radical idea in favor of the status quo. The call to work more, particularly when it comes from those perceived to be out of touch with the realities of everyday labor, is met with skepticism, frustration, and a strong desire for systemic change.