Recent American history suggests a complex relationship between citizen armament and law enforcement professionalism, paradoxically offering greater legal protection to those posing a physical threat when resisting a hostile federal agency. This line of reasoning implies that individuals resisting the current regime might benefit from arming themselves and forming organized community associations, akin to well-regulated militias. However, a significant counterargument posits that this moment of resistance is not primarily about power but, like the civil rights movement, is rooted in a fundamentally Christian struggle.

Read the original article here

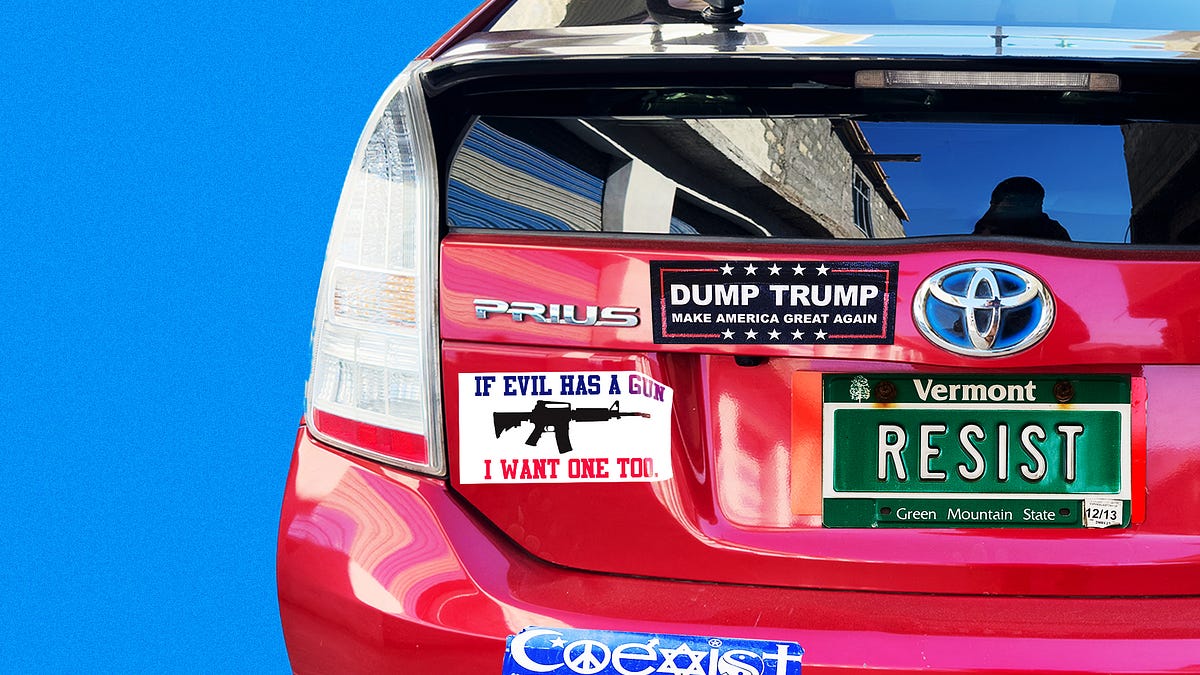

The question of whether liberals should start arming themselves, and by extension, engage in the formation of militias, is a complex one that sparks significant debate. It’s not a simple “yes” or “no” answer, but rather a nuanced discussion with compelling arguments on both sides. The idea that liberals don’t own guns is, for many, a misconception. A significant number of liberals already possess firearms, often quietly, without the overt display sometimes associated with gun ownership. It’s a personal choice, much like the decision to have an abortion is for many conservatives – a right exercised privately rather than a public statement.

The notion of needing to be capable of violence to be truly peaceful is a recurring theme. The argument is that peace without the capacity for defense isn’t true peace; it’s merely harmlessness. Bullies, whether they are individuals or institutions, tend to target those they perceive as unable to fight back. This perspective suggests that disarming citizens, particularly in times of perceived political instability or the erosion of constitutional rights, is a dangerous proposition, potentially leaving them vulnerable to those who do not adhere to the rule of law. The idea that the Second Amendment is for everyone, and its purpose is to guard against tyranny, resonates strongly with this viewpoint.

However, the idea of arming oneself and the concept of forming militias are not necessarily the same, and conflating them can lead to flawed strategies. While personal armament might be seen as a sensible precaution for self-defense in uncertain times, the historical data on the effectiveness of violent resistance versus peaceful movements presents a different picture. Studies analyzing various campaigns suggest that nonviolent resistance has a statistically higher success rate, not only in achieving immediate goals but also in securing positive long-term outcomes. Violent uprisings, even those with noble intentions, can sometimes devolve into new forms of oppression or fail to achieve lasting societal change, leaving behind a population susceptible to backlash.

Furthermore, the practicalities and dangers of widespread gun ownership, especially without adequate training, are significant concerns. The argument that owning a gun in the home statistically increases the risk of accidental death or injury is valid. The emphasis on rigorous, ongoing training is crucial, as proficiency with a firearm is paramount to its safe and effective use. Simply owning a gun for emergencies, without consistent practice, can turn a potential solution into an added danger. Safety rules, such as treating every gun as loaded and never pointing it at anything one doesn’t intend to destroy, are fundamental but require constant reinforcement through practice.

The discussion around militias also touches upon the idea that when people start talking about them, it often signifies a breakdown in trust and the perceived failure of established systems to act as impartial arbiters. This suggests that the need for citizen militias arises not from a desire for empowerment, but from a state of desperation when faith in institutions wanes. Framing this as a casual lifestyle choice, rather than a stark warning sign of societal instability, is seen by some as deeply problematic.

The historical context of movements for social change also offers valuable insights. Some argue that the Civil Rights movement, while achieving legislative victories, did not fundamentally alter the deeply ingrained attitudes of segregationists, who merely became more discreet. The hypothetical scenario of a more militant leadership, perhaps inspired by figures like Malcolm X, suggests that a more forceful approach could have led to more profound and lasting institutional and generational changes, even potentially a civil war-like struggle against systemic racism. Similarly, the women’s rights movement and others are viewed through this lens, where the incentive for change, though not always the means, often involved the threat or reality of force.

In the current political climate, the rise of fascism is sometimes linked to the economic pressures created by climate change and capitalism’s inherent need for infinite growth in a finite system. In this view, fascism emerges as a mechanism for the wealthy to preserve their advantage amidst declining resources. The idea of negotiating with those in power is seen as futile; change, it is argued, often comes through being “violently dethroned” and having the systemic power structures dismantled. The failure of many revolutions, according to this perspective, lies in not sufficiently disenfranchising the old guard and re-educating subsequent generations.

Ultimately, the question of whether liberals should arm themselves is deeply personal, tied to individual perceptions of safety and the direction of society. While many liberals already own guns and believe in the Second Amendment, the broader question of forming militias and engaging in any form of armed action is met with caution by some, who point to the historical efficacy of nonviolent strategies. The conversation highlights a spectrum of beliefs, from those who see personal armament as an obvious necessity in the face of potential authoritarianism, to those who remain concerned about the risks of gun ownership and the potential for violence to be counterproductive. The debate is less about whether liberals *can* arm themselves, but rather whether, how, and under what circumstances they *should*.