Stand with a newsroom committed to unwavering journalistic integrity. Membership empowers independent reporting, ensuring that critical stories are told without compromise. Support this vital work and ensure the continued delivery of news with backbone.

Read the original article here

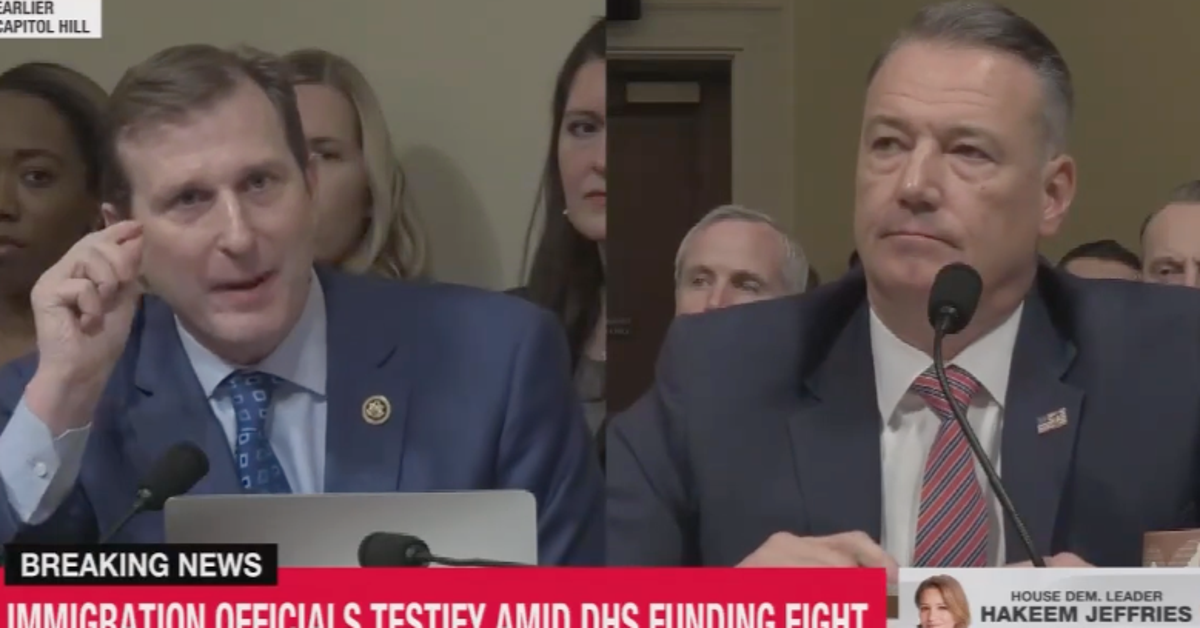

The recent kerfuffle involving the Acting Director of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), Todd Lyons, and his evident displeasure at being labeled a “fascist” or compared to the “Gestapo” or “secret police” has sparked quite a conversation, and frankly, the advice he received is remarkably straightforward, if a bit blunt: stop acting like one. It’s a sentiment that seems to resonate, even if it’s not the answer Lyons was hoping for when he lodged his complaint before the House Committee on Homeland Security.

The core of the issue, as articulated by Representative Dan Goldman, is that the label, while perhaps emotionally charged, is based on observed tactics. When an agency is seen regularly stopping individuals based on their perceived ethnicity or immigrant status to demand identification, as Goldman pointed out, it inevitably conjures historical parallels to regimes that operated on similar principles. This isn’t about a personal attack on the men and women of ICE, but rather a critique of the operational methods.

Lyons’ concession that secret police in Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union engaged in similar practices, while then attempting to dismiss the comparison as unfair, highlights a disconnect. It’s akin to saying, “Yes, our actions mirror those of oppressive regimes, but *we* are different because we say we are.” This argument, unsurprisingly, doesn’t quite land. The very act of stopping people based on appearance, a hallmark of authoritarian control, is what fuels these comparisons, regardless of the intent claimed by the agency.

The discussion also veered into the agency’s approach to enforcement, with Representative Eric Swalwell bringing up Lyons’ previous wish for a “deportation machine” likened to Amazon Prime, but with human beings. The stark contrast between efficient delivery services and the tragic reality of ICE’s use of force, including the fatal shooting of Renee Good and the killing of Alex Pretti, further underscores the gravity of the situation. When a delivery service doesn’t shoot people, and ICE does, the “efficiency” argument quickly crumbles under the weight of such violence.

The notion that ICE deals with “human beings” and therefore cannot operate like Amazon, while true, doesn’t absolve them from criticism regarding their methods. In fact, it amplifies it. Treating individuals with a level of detachment that leads to fatal outcomes, or stopping them based on appearance, is precisely what leads to comparisons with historical figures and movements known for their dehumanization and brutality. The comparison isn’t an arbitrary insult; it’s a reflection of the perceived operational style.

It seems the central piece of “revolutionary advice” boils down to a very simple premise: actions have consequences, and labels often arise from those actions. If an entity consistently exhibits behaviors associated with a particular ideology or historical entity, then the public discourse will naturally reflect that association. The discomfort with the label “fascist” doesn’t magically erase the actions that prompt it.

The idea that complaining about being called a fascist while engaging in practices deemed fascist is “classic GOP” behavior, as some observers have noted, points to a perceived pattern of deflection and victimhood. The argument that ICE is the enemy, or that the directives come from higher up, while potentially containing a kernel of truth regarding the political landscape, doesn’t absolve the operational arm from scrutiny. The “thin blue line” mentality, where law enforcement is seen as infallible, often clashes with the reality of individual incidents and the broader societal impact of an agency’s practices.

Ultimately, the conversation around Lyons and ICE serves as a potent reminder that in public discourse, perception is heavily influenced by observable actions. The plea to stop being called a fascist, while understandable from an individual’s perspective, is met with the equally straightforward and arguably more pragmatic response: if you don’t want to be called a fascist, then don’t do fascist things. It’s a principle that applies broadly, not just to government agencies, but to any entity whose actions evoke deeply negative historical associations. The weight of history, and the language it has bequeathed us, is not easily dismissed.