Justice Neil Gorsuch issued a sharp concurring opinion, criticizing his conservative colleagues for inconsistent application of the “major questions doctrine.” This doctrine requires clear congressional authorization for policies of significant national impact. Gorsuch highlighted that the doctrine was invoked to overturn President Biden’s student loan forgiveness, yet some justices who previously supported its use dissented in the current ruling against former President Trump’s tariffs. He also noted that liberal justices, who have historically criticized the doctrine, did not object to its use in this instance.

Read the original article here

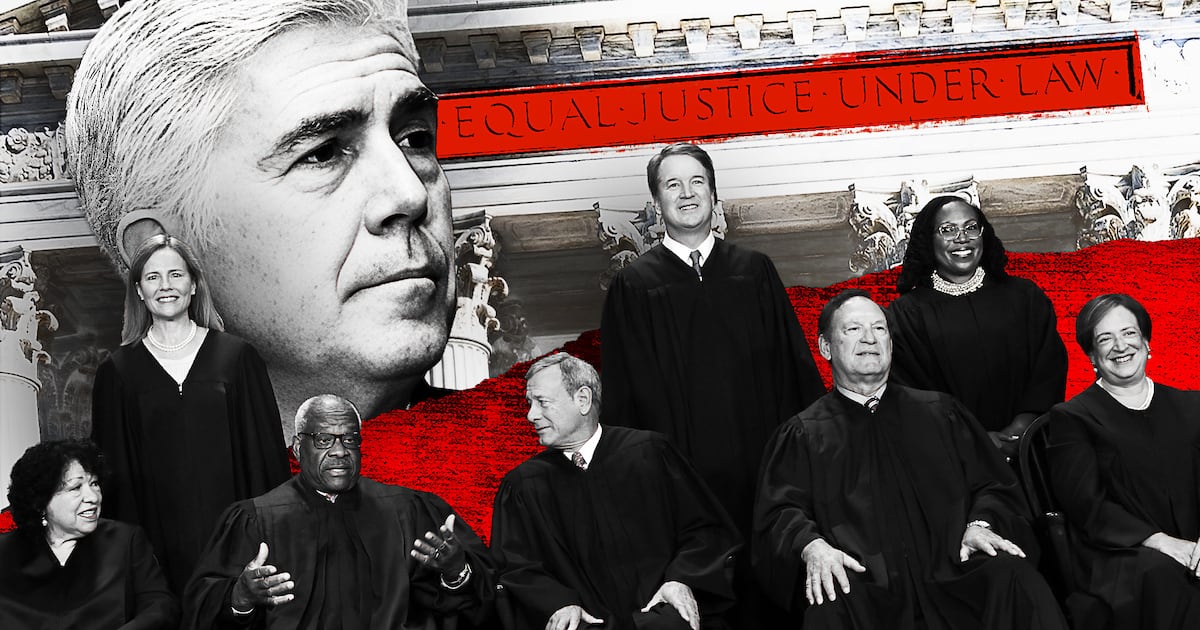

The notion of a “civil war” erupting within the Supreme Court, specifically a conservative justice launching an internal conflict against supposed MAGA hypocrites on the bench, is a dramatic assertion that, upon closer examination, reveals a more nuanced internal debate. While the term “civil war” is often employed for sensationalism, particularly by certain media outlets, it highlights a perceived tension and disagreement among the conservative justices, especially when confronted with cases that challenge their long-held ideologies or political allegiances.

This internal friction seems to stem from a clash between established legal doctrines and the perceived pressure to align with a specific political agenda. One particular point of contention appears to be the “major questions doctrine,” a principle championed by Justice Gorsuch. This doctrine generally limits the ability of executive agencies to issue broad regulations without clear authorization from Congress, often serving to curb the power of the administrative state.

When this doctrine, typically deployed to stymie Democratic initiatives, ended up hindering a Republican cause in a specific case, it exposed a potential inconsistency in its application. Gorsuch, it seems, was not entirely pleased with how the court handled this, especially when liberal justices were able to argue their case effectively based on statutory interpretation without resorting to the major questions doctrine, which they generally oppose.

Gorsuch’s actions suggest a strategic imperative. By not allowing the doctrine to be twisted or inconsistently applied, he may have been safeguarding its future utility. His apparent move wasn’t necessarily an attack on his conservative colleagues but rather a protection of his preferred legal framework, aiming to prevent it from being undermined in a way that could later be exploited by opposing ideological factions. He might have been signaling that, when the political winds shift, the doctrine will still be available for use.

The characterization of these judicial disagreements as a “civil war” is frequently seen as hyperbole, often fueled by headlines designed to generate clicks rather than convey accurate reporting. Many observers express frustration with the media’s tendency to sensationalize every internal dispute within political spheres, leading to a cascade of similarly dramatic, and often misleading, narratives.

Indeed, some argue that the court’s actions have often demonstrated a willingness to “reinvent the law” to achieve desired outcomes. There’s a sentiment that, for a significant period, the court has been politicized and compromised, with certain justices acting as though they are unaccountable or serving external interests rather than upholding the integrity of the law.

The criticism often leveled is that certain justices have been “bought and paid for,” implying a susceptibility to external influence and a departure from impartial judicial conduct. This suspicion is amplified when the court appears to struggle to find legal justifications for rulings that might have favored certain political figures, suggesting that even ideological allies can be forced to confront the limits of legal manipulation.

The idea that the court is “compromised” is not new, with some suggesting that its politicization predates recent events. The presence of justices perceived as acting more like political operatives than impartial arbiters fuels this distrust. This leads to a feeling that the court is not acting independently but is instead serving a particular agenda, potentially part of a larger plan orchestrated by wealthy individuals or ideological groups.

The conservative legal project, often associated with originalism, is perceived by some as a long-term endeavor that requires strategic maneuvering. Justices who foresee future political shifts might be acting with an awareness that their current actions, even if seemingly contradictory, are designed to preserve their influence and the longevity of their ideological aims. This can be interpreted as a calculated, albeit perhaps cynical, approach to judicial power.

The criticism often extends to specific justices, with accusations ranging from being “fascist ignorant psychopaths” to being motivated by personal gain. The suggestion that some justices are receiving “bribes” or acting under duress from external forces is a recurring theme, reflecting a deep distrust in their impartiality and motivations.

The wife of one justice, for instance, has been cited as evidence of potential conflicts of interest, with her alleged communications aiming to overturn election results fueling speculation about broader external pressures on the justice himself. This suggests a belief that personal or political loyalties might be influencing judicial decisions, rather than a pure adherence to legal principles.

Ultimately, the narrative of a “civil war” within the Supreme Court, while perhaps an overstatement, points to genuine disagreements and strategic calculations among its conservative members. These internal tensions are often framed by external forces and a public perception that the court’s integrity is at stake, leading to a complex interplay of legal doctrine, political pressure, and public scrutiny.