The Supreme Court’s decision on President Trump’s tariffs revealed a significant split among justices appointed by Republican presidents. Justice Gorsuch, in a concurring opinion, highlighted the inconsistency of his dissenting colleagues’ application of the major questions doctrine. While these justices previously invoked the doctrine to limit executive power in cases involving domestic policy like student debt cancellation, they failed to apply it when it would have constrained presidential authority over tariffs. This selective application raises questions about the integrity of their legal reasoning, particularly when contrasted with their past votes on similar issues, such as environmental regulation.

Read the original article here

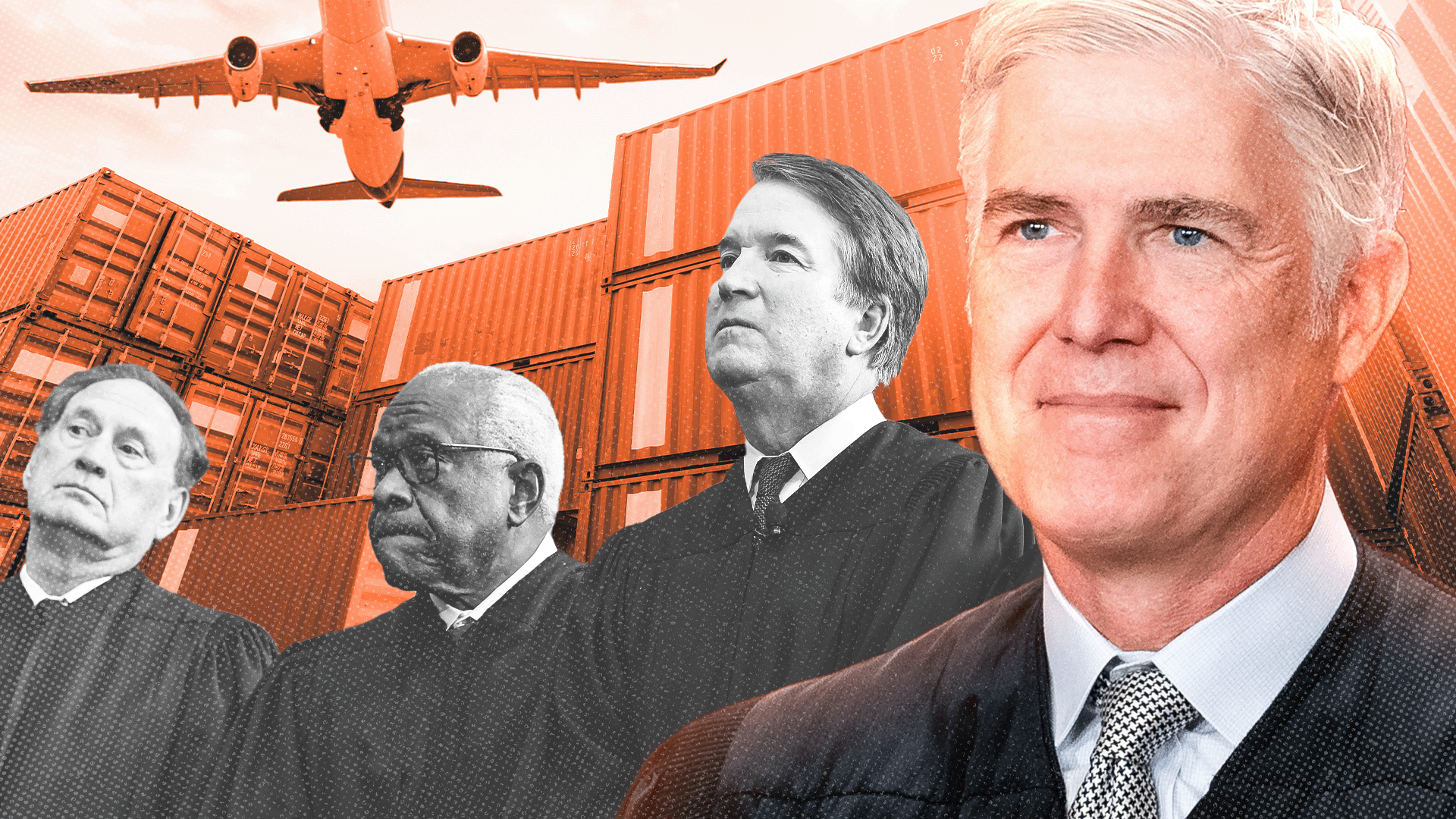

Justice Neil Gorsuch has voiced strong criticism regarding the Supreme Court’s recent decisions, particularly highlighting what he perceives as a significant inconsistency in the judicial philosophy of Justices Thomas, Alito, and Kavanaugh when it comes to executive power and presidential actions. This critique centers on their differing approaches to what is known as the “major questions doctrine,” a legal principle that requires clear congressional authorization for significant executive branch actions.

The core of Gorsuch’s concern appears to stem from the Supreme Court’s handling of two key cases. In one instance, the court, relying on the major questions doctrine, struck down President Biden’s plan for student debt cancellation, arguing that Congress had not unambiguously delegated such broad power to the executive. Justices Thomas, Alito, and Kavanaugh were among those who supported this decision, emphasizing the need for congressional imprimatur on sweeping policy changes.

However, in a subsequent case involving President Trump’s tariffs, the same justices, according to Gorsuch’s implied criticism, seemed to overlook or apply the major questions doctrine differently. The implication is that they were willing to allow President Trump to implement significant tariffs, an action that arguably falls under the purview of executive overreach that they previously so strongly opposed when exercised by President Biden. This perceived flip-flop has led to accusations of political bias rather than consistent application of legal principles.

Gorsuch, while not explicitly labeling his colleagues as hypocrites, points to this stark contrast in their rulings. He observes that while the dissenting justices have championed the major questions doctrine in the past, their recent actions suggest a willingness to grant leeway to one president that they denied to another. This inconsistency, he implies, raises serious questions about the impartiality and principled application of the law by these justices.

The doctrine itself is designed to prevent the executive branch from assuming powers that rightfully belong to Congress. It dictates that for the executive to wield significant regulatory authority, there must be explicit statutory backing from the legislature. This safeguard is intended to maintain the balance of power within the government, preventing the erosion of legislative authority through executive decree.

The legal precedent set in the student loan case, where the court invoked the major questions doctrine to invalidate Biden’s initiative, was repeatedly cited in the context of the Trump tariffs case. The expectation, based on their previous stance, would have been for Thomas, Alito, and Kavanaugh to apply the same doctrine to challenge Trump’s tariff actions. Their perceived departure from this established reasoning has fueled concerns about their commitment to an objective interpretation of the law.

This situation has led to widespread discussion about the credibility of the justices involved. The question of whether this glaring inconsistency will damage their future standing and the Court’s reputation is now a prominent point of debate. Many observers feel that their credibility has already been compromised, particularly given the public perception that their rulings are influenced by political affiliations rather than pure legal analysis.

There is a sentiment that in the current political climate, justices are expected to be loyal to a particular ideology or political figure, rather than solely to the Constitution. This is compounded by public commentary that suggests some justices have personal entanglements that could influence their impartiality, further eroding trust in their judicial pronouncements.

The consistency of legal interpretation is fundamental to the integrity of the judiciary. When justices appear to apply legal doctrines selectively, depending on the political party of the president, it undermines the public’s faith in the Supreme Court as an impartial arbiter of justice. Gorsuch’s critique, therefore, is not just about a single ruling, but about a broader concern for the preservation of judicial principles and the rule of law.

The debate also touches upon the notion of what it means to be an “originalist” or to adhere to a particular judicial philosophy. Critics suggest that when these philosophies lead to outcomes that appear politically motivated, they serve more as a justification for partisan decisions than as genuine guides for legal interpretation.

Ultimately, Gorsuch’s commentary highlights a critical juncture for the Supreme Court. The perceived inconsistency in how the major questions doctrine has been applied, particularly concerning actions by different administrations, raises serious questions about the Court’s impartiality and its commitment to upholding the fundamental principles of justice and governmental balance. The lasting impact of these perceived inconsistencies on the Court’s credibility remains a significant concern for the future.