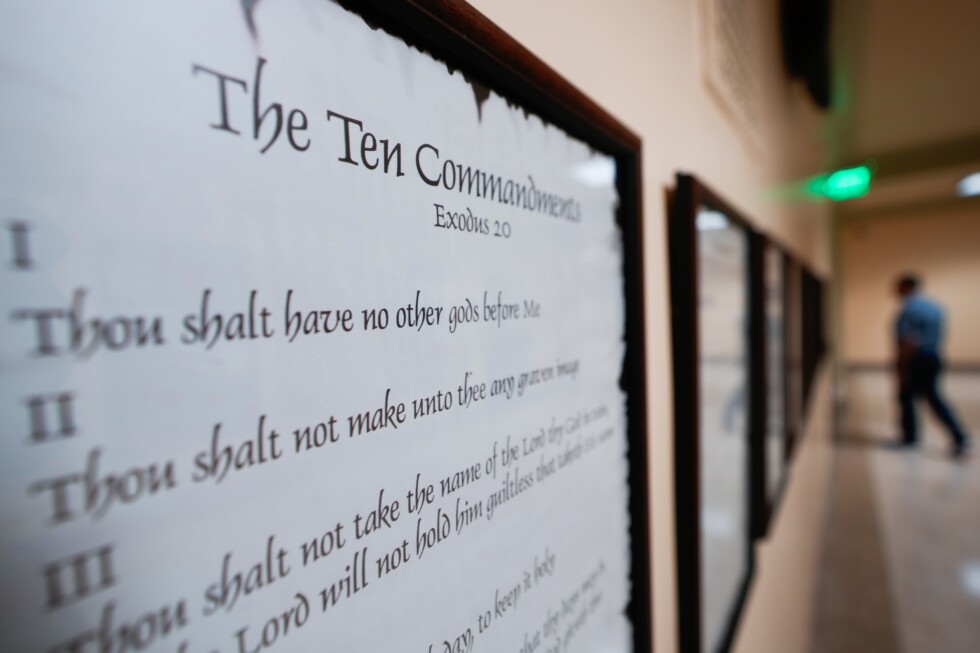

A U.S. appeals court has lifted a block on a Louisiana law requiring public schools to display the Ten Commandments, voting 12-6 to allow the statute to proceed. The court’s majority opinion stated that it was too early to judge the law’s constitutionality, citing insufficient details on how the displays would be implemented and used in classrooms. While supporters hailed the decision as a victory for common sense and tradition, opponents vowed to continue legal challenges, asserting the law unconstitutionally promotes religion in schools. This ruling follows a trend of similar laws being enacted and contested across the nation, with the debate centering on the separation of church and state versus the historical significance of the Ten Commandments.

Read the original article here

A significant development has occurred in Louisiana, where a U.S. appeals court has effectively paved the way for a state law mandating the display of the Ten Commandments in public school classrooms to be implemented. This decision by the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, with a majority vote of 12-6, has lifted a previous injunction that had halted the law back in 2024. The court’s reasoning, as outlined in its opinion released on a Friday, suggests that it is premature to definitively rule on the constitutionality of the legislation at this juncture.

In a notable concurring opinion, Circuit Judge James Ho, appointed by former President Donald Trump, expressed a strong view that the law is not only constitutional but also serves to uphold the nation’s most cherished traditions. This perspective highlights a fundamental division in how the law is being perceived and interpreted within the judicial system.

Conversely, the six judges who dissented voiced serious concerns, arguing that the law imposes government-endorsed religion upon children in an environment where their attendance is compulsory. This, they contend, creates a direct constitutional conflict. Circuit Judge James L. Dennis, appointed by former President Bill Clinton, articulated this sentiment powerfully in his dissent, stating that the law represents precisely the kind of religious establishment that the nation’s founders intended to prevent.

The core of the legal debate appears to revolve around the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause, which prohibits the government from establishing a religion. Critics of the Louisiana law question how mandating the display of religious texts in public schools aligns with this fundamental principle, particularly the concept of freedom from religion, which is considered an integral part of religious freedom itself. There’s a palpable frustration that such debates resurface periodically, often coinciding with shifts in political power, suggesting a pattern of pushing religious agendas onto public institutions.

The argument is made that if the government is to mandate the display of religious tenets, then a consistent application would necessitate holding government officials accountable for adhering to these commandments, questioning whether their presence in classrooms is purely decorative or intended to signify moral governance. The idea is also raised that if one religious text is displayed, then other religious or even secular doctrines should also be permitted, leading to a potential free-for-all or, conversely, highlighting the problematic nature of any single endorsement.

The timing of this ruling and the ongoing legal challenges prompt questions about the judiciary’s interpretation of constitutional principles, with some characterizing the 5th Circuit as having a particular ideological bent. The notion that it’s “too early to make a judgment call on constitutionality” is viewed by many as an evasion, as laws are generally expected to be either constitutional or not. This leads to broader discussions about whether fundamental rights are being respected or disregarded in the pursuit of political or ideological goals.

There’s a prevailing sentiment that the law represents a push toward a form of governmental control that borders on or is analogous to fascism, citing specific characteristics often associated with such regimes. This is seen as a troubling sign, especially given the historical precedents and legal challenges that have repeatedly struck down similar attempts to mandate religious displays in public settings. The argument is that such actions demonstrate a disregard for established legal precedent and a pattern of behavior that prioritizes ideology over constitutional law.

The inherent irony is not lost on many that proponents of the Ten Commandments in schools may themselves not adhere to all of them, especially when considering public figures and past actions. This perceived hypocrisy fuels skepticism about the genuine intent behind such legislation, leading to accusations that it’s less about morality and more about imposing a specific religious viewpoint. The concern is that this infringes upon the rights of individuals to practice their own beliefs, or no beliefs at all, without government coercion.

The potential for the law to be challenged all the way to the Supreme Court is high, with many believing that existing legal interpretations, particularly concerning the Establishment Clause, will ultimately lead to its downfall, as has happened in previous cases involving similar laws in other states. The repeated nature of these legal battles, often ending in unfavorable rulings for the proponents, leads to accusations that those pushing the laws are willfully disregarding precedent and wasting public resources and time. This cycle of legal challenges and eventual defeats suggests a persistent, almost obstinate, effort to blur the lines between church and state.

The broader implication is that these efforts undermine the very concept of religious freedom, which is understood to include the freedom *from* religion. Forcing religious displays on students who may not share those beliefs, or any beliefs, is seen as a violation of their fundamental rights. The debate often devolves into accusations of hypocrisy and a perceived attempt by certain political factions to equate their religious beliefs with national identity or to impose a particular moral code through governmental authority.

The contentious nature of these issues often elicits strong reactions, with some suggesting that if religious texts are to be displayed, then other religious or philosophical doctrines should also have a place, leading to proposals like displaying the tenets of the Satanic Temple as a counterpoint. This highlights the perceived unfairness and selective application of religious expression in the public sphere, and the potential for such mandates to be seen as proselytizing rather than acknowledging diverse beliefs. The current legal landscape, with the appeals court’s decision, suggests that this debate is far from over and will likely continue to be a source of legal and social contention.