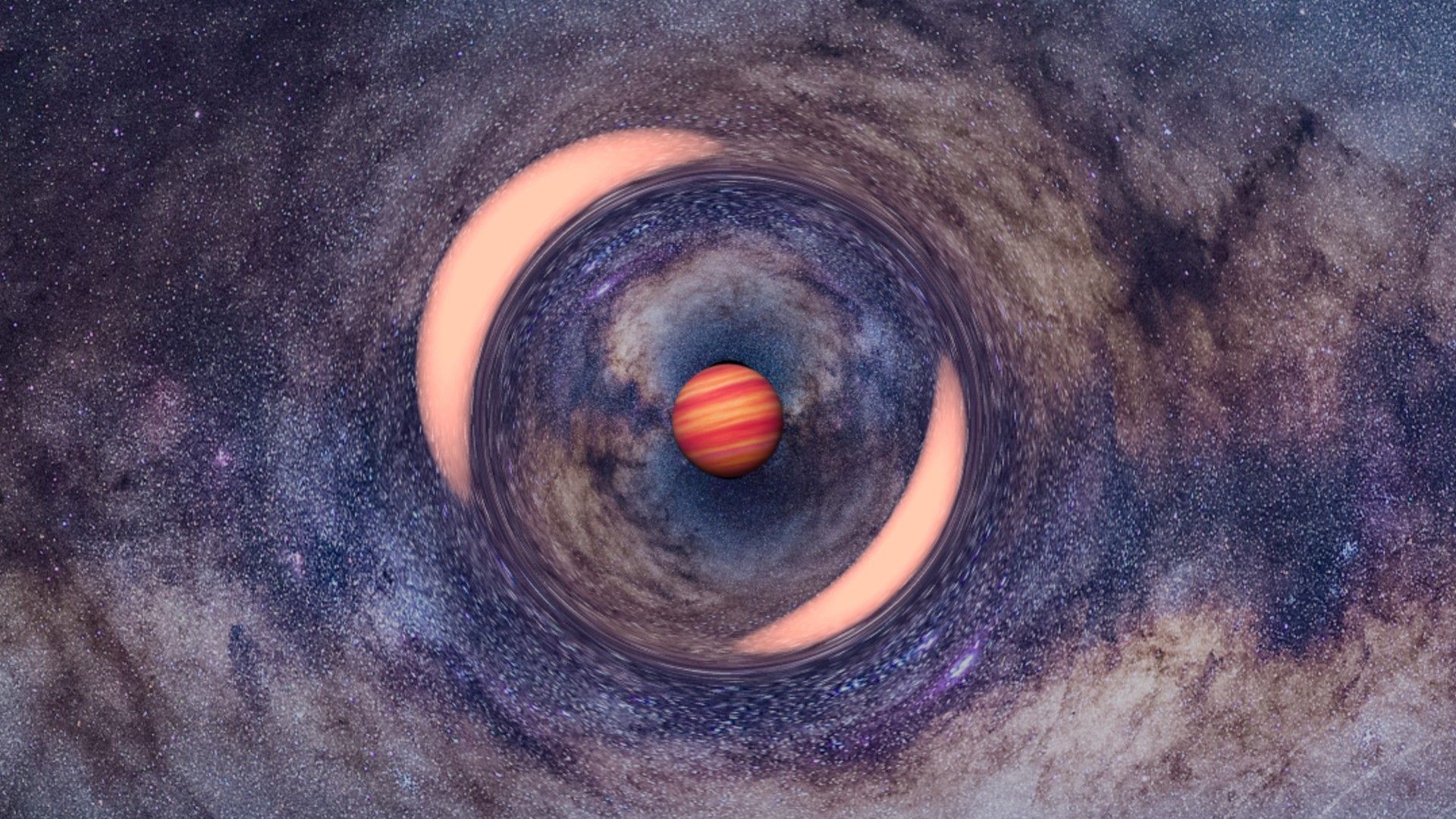

Scientists have confirmed the existence of a rogue planet, a starless world, for the first time by determining its distance and mass. Using gravitational microlensing, the astronomers observed an object distorting light from a distant star, approximately 9,950 light-years from Earth, with a mass about 70 times that of Earth. This discovery, made possible by observations from multiple observatories and the Gaia space telescope, suggests that these free-floating planets are likely abundant in the Milky Way, even more numerous than the stars themselves. The newfound data will assist in understanding planet formation and how some planets become rogue, while upcoming telescopes promise to find even more of these wandering worlds.

Read the original article here

Astronomers detect rare ‘free floating’ exoplanet 10,000 light-years from Earth, and it’s quite the discovery, isn’t it? It’s like finding a needle in a haystack, except the haystack is the vast expanse of space, and the needle is a planet that doesn’t orbit any star. That’s right, this is a “free-floating” exoplanet, wandering alone in the interstellar void, roughly 10,000 light-years away from us. It’s hard to wrap your head around the scale of that, but it highlights just how advanced our detection methods have become.

This remarkable discovery was made using a technique called gravitational microlensing. Essentially, it relies on the way gravity bends light. When a massive object, like a planet, passes in front of a distant star from our perspective, its gravity acts like a lens, magnifying and distorting the star’s light. By carefully observing the changes in the star’s brightness, astronomers can infer the presence of a foreground object, even if it’s not emitting any light of its own. It’s a clever trick, and it’s what allowed them to identify this wandering world.

The exoplanet is estimated to have a mass similar to Saturn. That detail, coupled with its lack of a host star, is what makes this discovery so significant. It raises questions about how such a planet could have formed and how it came to be ejected from its original star system. One prevailing theory suggests that these free-floating planets are “orphaned” planets, ejected from their systems due to gravitational interactions with other planets. Imagine a cosmic game of billiards, where planets get knocked out of their orbits and sent hurtling through space.

Considering the vast distances involved and the general lack of resources, the likelihood of humans going to this planet is quite slim. It’s important to keep things in perspective. This planet’s journey is going to continue indefinitely. It might eventually enter a new solar system, affecting orbits, or even collide with another planet. It’s truly a thought-provoking concept.

The fact that this planet isn’t orbiting a star raises the inevitable question of whether it could support life. Without a star to provide warmth and light, it’s highly unlikely that the conditions for life as we know it could exist on the surface. However, some scientists speculate that if the planet had subsurface geothermal activity or oceans kept warm by internal heat, it’s not entirely impossible that extremophile life forms similar to those found near ocean vents here on Earth could exist. It’s certainly a fascinating possibility to consider.

The detection of this rogue planet also opens up a whole new realm of possibilities for understanding planetary formation and evolution. There are probably many, many planets that have been ejected from their star systems. The number of such planets could be staggering. How common is it for planets to get ejected, and how likely it is that Earth could face a similar fate someday? These are exciting questions that future research can now address.

The discovery itself is a testament to human ingenuity and our relentless curiosity about the universe. It serves as a reminder that there’s still so much out there to explore and discover. It’s moments like these that capture the imagination and inspire us to keep looking up, keep asking questions, and keep pushing the boundaries of what we know.