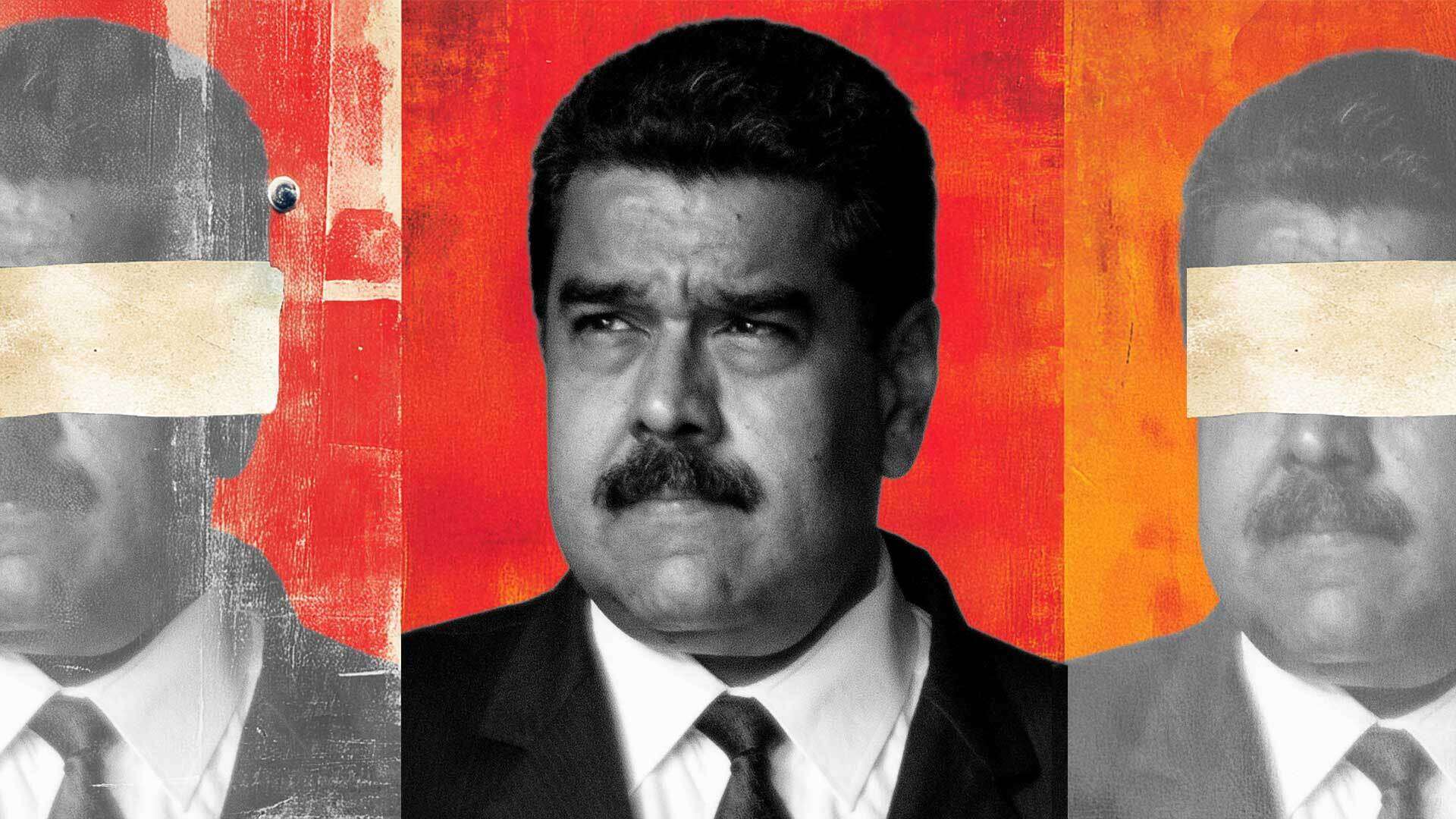

The Justice Department’s revised indictment of Nicolás Maduro, while still accusing him of “narco-terrorism” and drug trafficking, now describes the Cártel de los Soles as a “patronage system” rather than a literal organization. This shift contrasts with the original 2020 indictment and highlights inconsistencies within the government, as the Treasury and State Departments continue to designate Cártel de los Soles as a Foreign Terrorist Organization. This designation is key for Trump, who has been using it rhetorically to justify policies, like the summary execution of suspected drug smugglers, blurring the lines between drug trafficking and violent aggression. Critics argue that the FTO label is being applied loosely, even when it lacks a strong legal or factual basis, particularly in cases like Cártel de los Soles.

Read the original article here

Why the DOJ Has Stopped Describing Maduro as the Head of a Literal Drug Cartel, it seems, is a question with a multi-layered answer, and the threads all weave a complex narrative. It’s important to understand the shift, especially considering how dramatically the political rhetoric has changed.

The heart of the matter seems to be a significant detail: the organization known as “Cártel de los Soles” isn’t a tangible entity. It’s not like the Cali Cartel or the Medellín Cartel, with clear structures, hierarchies, and defined operations. Instead, it seems to have been more of a figure of speech, a label used to describe the corruption and patronage system within the Venezuelan government. This distinction, though subtle, is critical when it comes to legal proceedings.

The initial strategy, seemingly, was to build a narrative. This is where it gets interesting, because the playbook appears to involve a strategy that has been seen before: make bold claims, generate headlines, and then, later, adjust or retract those claims without much fanfare. This is the tactic. Make the initial claims bombastic. But the media, and perhaps more importantly, the public, are more likely to notice the initial headlines than they are to follow up on any subsequent corrections or retractions. Because the corrections never reach the same audience as the original claims, and the corrections are only for the record.

There’s also the legal aspect to consider. When building a case, facts are paramount, and feelings are irrelevant. The prosecution needs concrete evidence, tangible links between Maduro and specific drug trafficking operations. If the case rests on a label – a “cartel” that isn’t really a cartel – then it becomes a lot more difficult to secure a conviction. Because the jury must only consider the facts presented.

This is where the political optics come into play. A failed prosecution is embarrassing. A failed prosecution that relies on accusations that are made up is a disaster for any administration, especially when it involves the leader of another nation. It’s a huge political gamble, and it would leave the US vulnerable to accusations of overreach and political gamesmanship.

It’s also worth noting the political motivations that could be involved. Perhaps the initial accusations were designed to achieve several things, even if a conviction was not the primary goal. They may have been part of an effort to pressure Maduro, to destabilize his government, or to influence the situation in Venezuela. They may have been designed to get headlines. However, the reality of evidence, or lack thereof, eventually catches up.

The whole situation also raises questions about the US’s jurisdiction in this kind of case. Can the US government legally prosecute a foreign leader for actions that occurred entirely within their own country, especially when those actions may not even be considered criminal under US law? The answer isn’t so clear cut and depends on international laws and the nature of the charges, but it opens the door to complicated legal challenges.

Essentially, the DOJ’s shift in language reflects a pragmatic adjustment to the legal realities of the situation. They made an accusation, but, perhaps, they never had the evidence to back it up. If you are going to accuse a leader of running a cartel, you’d better have clear proof of his direct involvement in drug trafficking. The shift isn’t an admission of guilt, or a reversal of policy. It is about a tactical adjustment.