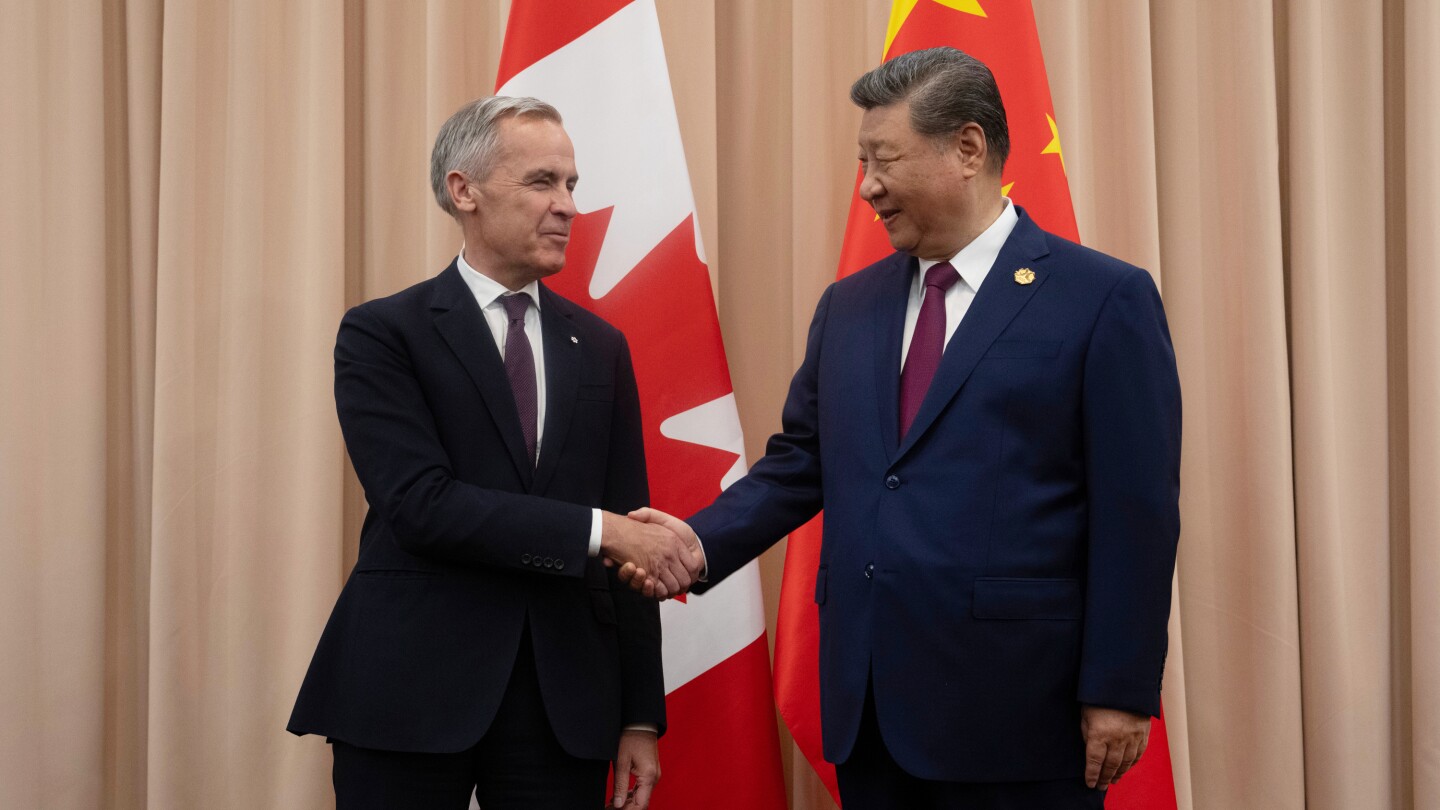

China hopes that the arrival of Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney will allow it to pull Canada away from the United States, calling for “strategic autonomy” in foreign policy. Beijing views the U.S.’s economic actions and military decisions as an opportunity to weaken the longstanding relationship between the U.S. and Canada. The visit is also seen as a chance to revive a relationship strained by the arrest of a Chinese tech executive and the imposition of tariffs. Though progress on trade is expected, experts suggest common ground might be found due to U.S. military intervention and territorial aspirations.

Read the original article here

China’s diplomatic overtures to Canada, particularly as Prime Minister Carney visits Beijing, are undeniably a focal point, sparking a complex web of reactions and considerations. The implicit message from China is clear: they’d like to see Canada loosen its close ties with the United States. This isn’t just about trade; it’s about strategic influence, and for China, the goal seems to be reshaping the geopolitical landscape.

The shadow of Donald Trump and his policies looms large in the background of this situation. The possibility of the US, under a Trump presidency, viewing closer Canadian-Chinese relations as a national security threat is a legitimate concern. This could lead to a scenario where the US attempts to exert greater control over Canada, which in turn could push Canada further towards China. It’s a dangerous game of political chess, where every move has significant repercussions.

The idea of strategic autonomy, of countries like Canada, the UK, Australia, and others finding their own footing independent of the superpowers, is appealing. The reality, however, is that both the US and China wield significant economic power, and navigating this landscape is a complex challenge. Finding a balance is key, reducing reliance on any single authoritarian state. Building stronger relationships within a democratic bloc, like the EU and perhaps a CANZUK partnership, offers a potential solution, though it does not yet have enough economic power to be a solution.

The reactions within Canada are interesting. There’s an awareness that China isn’t a benevolent actor. There are concerns about its human rights record and its long-term strategic goals. Yet, there’s also the recognition that the US, under certain administrations, can be a difficult partner. It’s a complicated picture, but the pragmatism is evident. They are not blinded by China’s marketing.

The potential for a US retreat from the global stage, whether intentional or not, opens up opportunities for China. China is already making aggressive moves in the EV sector. The question remains, can Canada be a smart partner in the changing dynamics?

The fact that the US has, at times, acted in ways that undermine its allies’ interests only accelerates this process. The US is losing influence because of its hostile actions. This doesn’t mean Canada is looking to make a defense pact with China. That’s probably not going to happen.

The historical context, particularly events like Tiananmen Square and the treatment of the Uyghurs, is a constant reminder of the nature of the Chinese regime. However, the comments show that many Canadians are open to trade relations with China so the US doesn’t have too much power over them, but still realizing that China is not a friend either, just another authoritarian imperialistic power.

The situation is a delicate dance. Canada, like many other nations, must balance its economic interests with its values and strategic security. This means trade deals, yes, but not at the expense of its sovereignty or its principles. China’s long-term vision and its strengths in areas like post-carbon technology create a difficult situation.

China is very good at playing the long game. For now, it seems necessary for Canada to seek a degree of diversification to protect itself against mercurial partners. The alternative, simply replacing one dominant power with another, isn’t a solution. A move toward a more diversified network of alliances, particularly with the EU, is the best route.

The potential consequences are serious. If China were to invade Taiwan, it would force every country to choose between their new trade partner and their commitment to Taiwan’s sovereignty. The choice for Canada would be difficult. Canada needs a strong and reliable defense partnership.

The economic implications are also clear. China is a major player in the post-carbon technology sector. They will soon take the tech lead from the US. Canada is a resource rich nation and is vulnerable as China attempts to monopolize the industries of tomorrow.

The situation is full of traps. The idea that this is a simple shift from one autocratic power to another is something that cannot be overlooked. Canada has to be aware that China is not going to be any better. Greater trade with China is fine, as long as it’s part of a broader strategy of diversification and collaboration with other countries.

The underlying frustration with the US is palpable. Canada, like other nations, is reevaluating its relationships in the face of shifting geopolitical realities. The world is evolving, and Canada must adapt carefully, staying aware of the risks and maintaining its own independence.