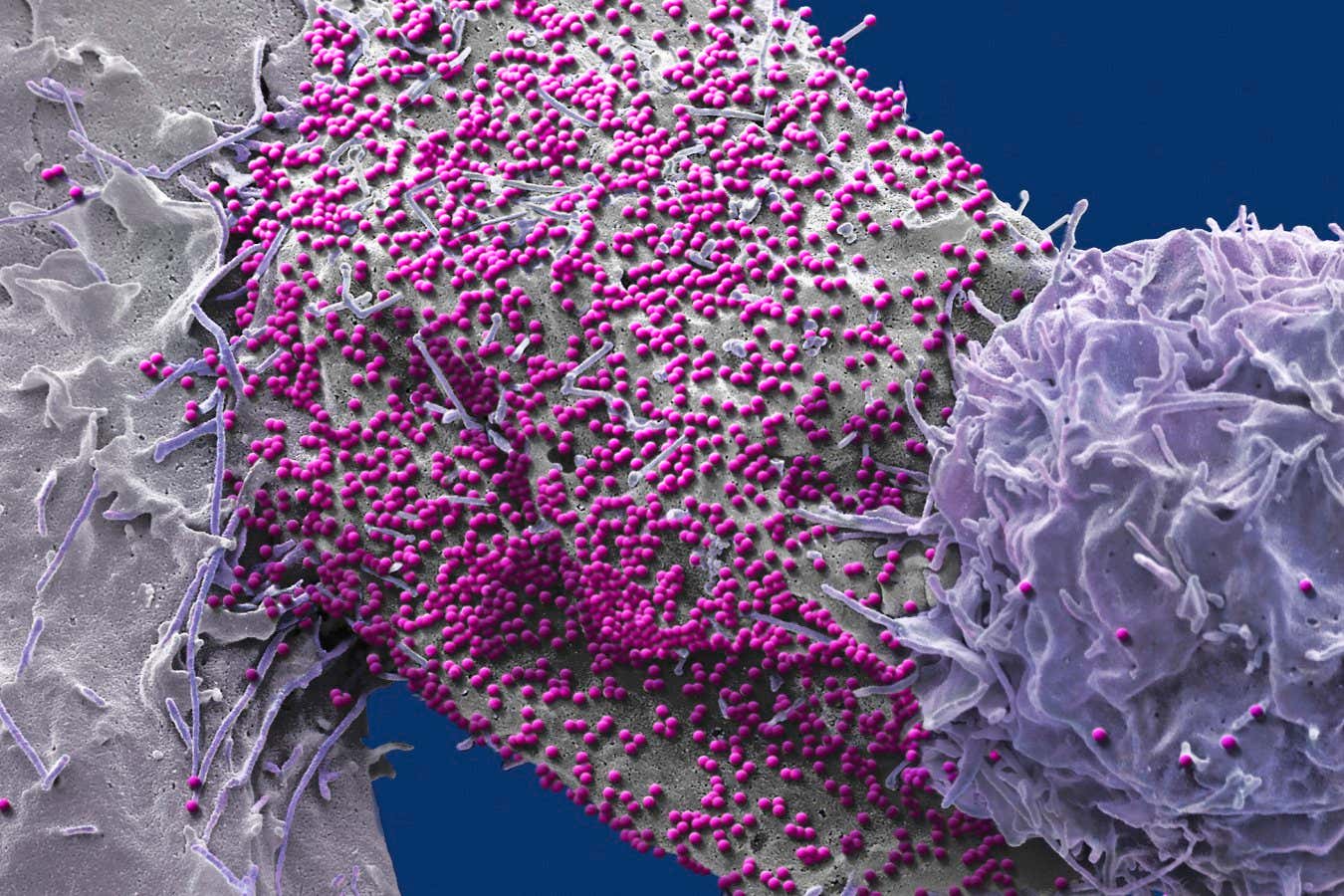

Recent research reveals a seventh individual has been successfully cured of HIV following a stem cell transplant, challenging previous assumptions. Unlike the first five individuals who received HIV-resistant stem cells, this patient, and the sixth, received non-resistant cells, indicating that HIV-resistance may not be essential for a cure. This suggests that the donor cells’ ability to eliminate the patient’s remaining immune cells may be crucial in preventing viral spread. This new understanding opens up the possibility that a broader range of stem cell transplants could potentially cure HIV, but that more research is needed, and that the patient’s and donor’s genetics may play a role.

Read the original article here

Okay, so here’s the headline: a man, out of the blue, seems to have been cured of HIV after receiving a stem cell transplant. Pretty wild, right? And, you know, it’s the kind of news that gets you thinking about all sorts of things, not just the science of it all. It’s like something out of a science fiction movie, except it’s real life.

Now, before we get too carried away, let’s be clear: this isn’t a readily available cure everyone can jump on. The patient also had leukemia, and the stem cell transplant was preceded by some pretty intense treatments, including chemotherapy and total body irradiation. This isn’t a quick fix or a scalable solution, at least not yet. But it is incredibly significant. It’s only the seventh documented case of a person seemingly being cured of HIV, out of the millions upon millions who have contracted the virus. That rarity alone makes this discovery incredibly valuable, because it provides insights into what might one day lead to a genuine cure. We’ve got incredible drugs to manage HIV, and people can live full lives with them. But it’s a lifetime of medication, which is a significant factor in any patients life. This, however, is a potential game-changer.

Of course, with any medical breakthrough, and especially one touching on sensitive topics, the conversation quickly moves beyond the scientific facts. This is where things get really interesting, or, depending on your perspective, a bit complicated. There’s a lot of talk about how certain groups might react. Some people are quick to point out the potential for controversy. The idea of stem cells, even though in this case, it appears to be a transplant of hematopoietic stem cells, which come from donors, often raises ethical concerns for some. There’s the fear that some will object, even if the research could cure HIV.

There are also the practical realities of the situation. Some might be hesitant, pointing out that this particular treatment involved things like intense chemotherapy and total body irradiation. That kind of treatment isn’t exactly a walk in the park, and it brings with it its own set of risks. The conversation always touches on the profitability of healthcare, and the argument that big pharma might not be interested in finding cures if they can make more money selling lifelong treatments. But, the medical field and specifically big pharma have been making big discoveries and innovations within drugs and treatments for several decades now. The reality is far more complex than a simple “good vs. evil” narrative.

Then there’s the broader discussion around medical experiments, with many bringing up the history of medical breakthroughs, including controversial ones. The question of informed consent comes up, and the debate surrounding bodily autonomy. And you know, we always circle back to the core question: Do we have the right to choose what happens to our bodies? It’s a conversation that gets to the heart of individual freedom and control.

However, the real crux of the issue may come down to what is most important for an individual, and the ability to decide what is the best choice for them. This extends to the broader political and social landscape. While there have been a lot of breakthroughs in stem cell research, with applications for veterinarians, that may be used to treat animals, it can also be used for humans.