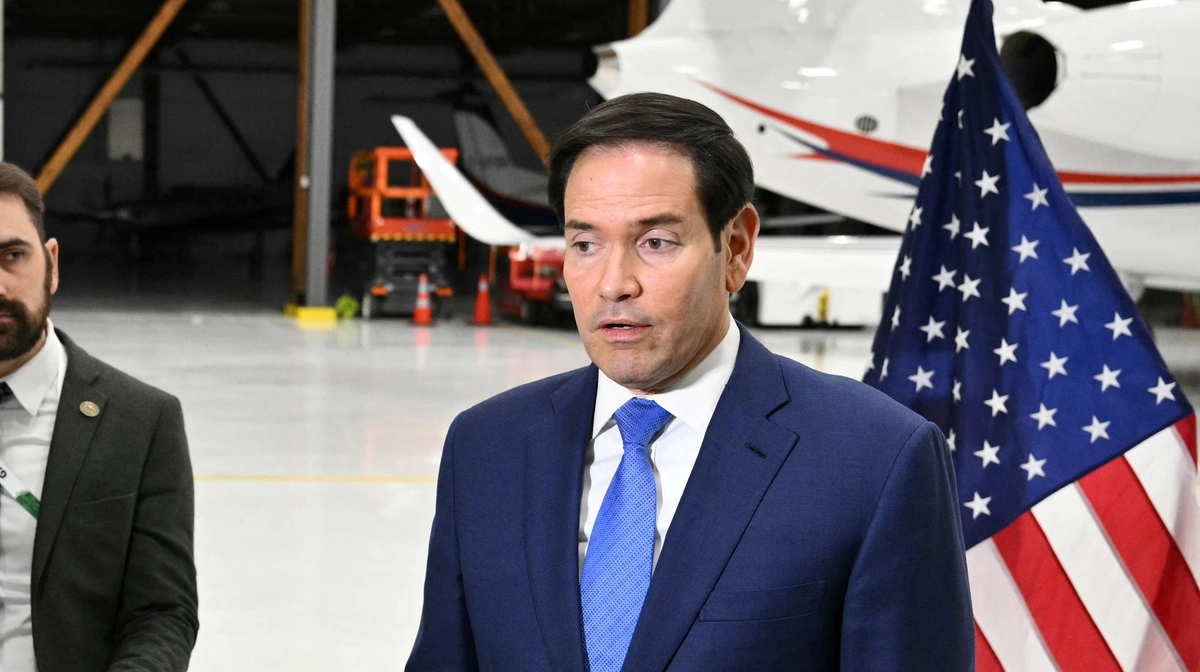

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio indicated that the US has largely exhausted its options for imposing new sanctions on Russia, having already targeted major oil companies. The focus will now shift to enforcing existing sanctions, particularly addressing Russia’s “shadow fleet” of vessels used to circumvent oil restrictions, with a call for greater European involvement in this effort. Rubio also commented on the ongoing conflict, stating Russia’s objectives and the missile strikes on Ukraine’s energy infrastructure. Finally, the US is in talks with Ukraine to stabilize its energy grid, discussing the provision of equipment and defensive weapons, while acknowledging the challenges of protecting such infrastructure from destruction.

Read the original article here

Rubio: US has exhausted potential to tighten sanctions against Russia. Well, that’s quite a statement, isn’t it? It implies that we’ve reached the limit of what we can do to pressure Russia through economic measures. But honestly, when you start to really think about it, does that ring true? The immediate gut reaction is, “No way!” There’s got to be more we could be doing. The idea that we’ve squeezed every last bit of leverage out of sanctions just doesn’t feel right.

They can try financing Ukraine’s kinetic sanctions maybe? This points to a whole different kind of pressure, a “kinetic” approach, which is a euphemism for military action. The current discussion of tariffs as an instrument of US foreign policy brings up a key question, what are the current US tariffs on Russian goods? Considering that some countries are getting socked with high tariffs on things like pasta, can’t we go even harder on Russia? The potential for significantly increasing tariffs seems like an obvious avenue that hasn’t been fully explored. This should be a no-brainer.

“We tried nothing and we are out of ideas!” Bullshit. That sounds like a pretty defeatist attitude, doesn’t it? When you’re dealing with a situation like this, the idea of having “exhausted all options” seems premature. It’s like saying we’ve reached the end of the road before even really trying. The truth is, sanctions could be tightened to the point of a complete embargo, which is something that has been done before. Consider Cuba, they’re still feeling the impact of actions taken decades ago.

Then there is the possibility of targeting countries that are trading with Russia. This can be achieved with secondary sanctions and could really put the squeeze on Moscow. A quick glance at the trade numbers between the U.S. and Russia, and between Russia and other nations, indicates the latter is far greater than the former. This alone would appear to give the US enormous leverage. This is something that could bring Russia to the negotiating table fast.

Secondary sanctions are also a thing. The US can also impose penalties and fines on Western companies whose goods keep showing up in Russian missiles, and track down those gray market suppliers. There is a whole world of options that still lie unexplored. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. What about targeting that “shadow fleet” of oil tankers, or those funds that may be hidden away in Euroclear?

We need to consider the more unconventional ideas. Some might say we could target the shadow fleet using submariners. Or, to put it more bluntly, it seems like we could get more direct with our confrontation. There’s also the whole issue of software updates for Russian PCs. Is Microsoft still sending them? What about proxy funds? The reality is there’s a lot more that can be done.

The data also show a pretty stark contrast in trade. The U.S. is trading a tiny fraction of goods with Russia compared to what it trades with other countries, like Italy. This means tariffs, while useful, may not be as effective as they could be if the trade volume were higher. And as far as tariffs go, isn’t it a little fishy that there’s talk of a 107% tariff on pasta from Italy next year?

Finally, the whole idea of “exhausting” sanctions is a dangerous one. It can create an environment where we are afraid to act, or act decisively. If we give up on the idea of applying pressure, we might as well give up on the entire cause. Let’s not forget, the U.S. isn’t at war with Russia, and we aren’t about to hurt ourselves just to help Ukraine, a country that we’re not formally allied to. This isn’t about being pathetic, it’s about being strategic. We need to be creative, persistent, and willing to go the distance.