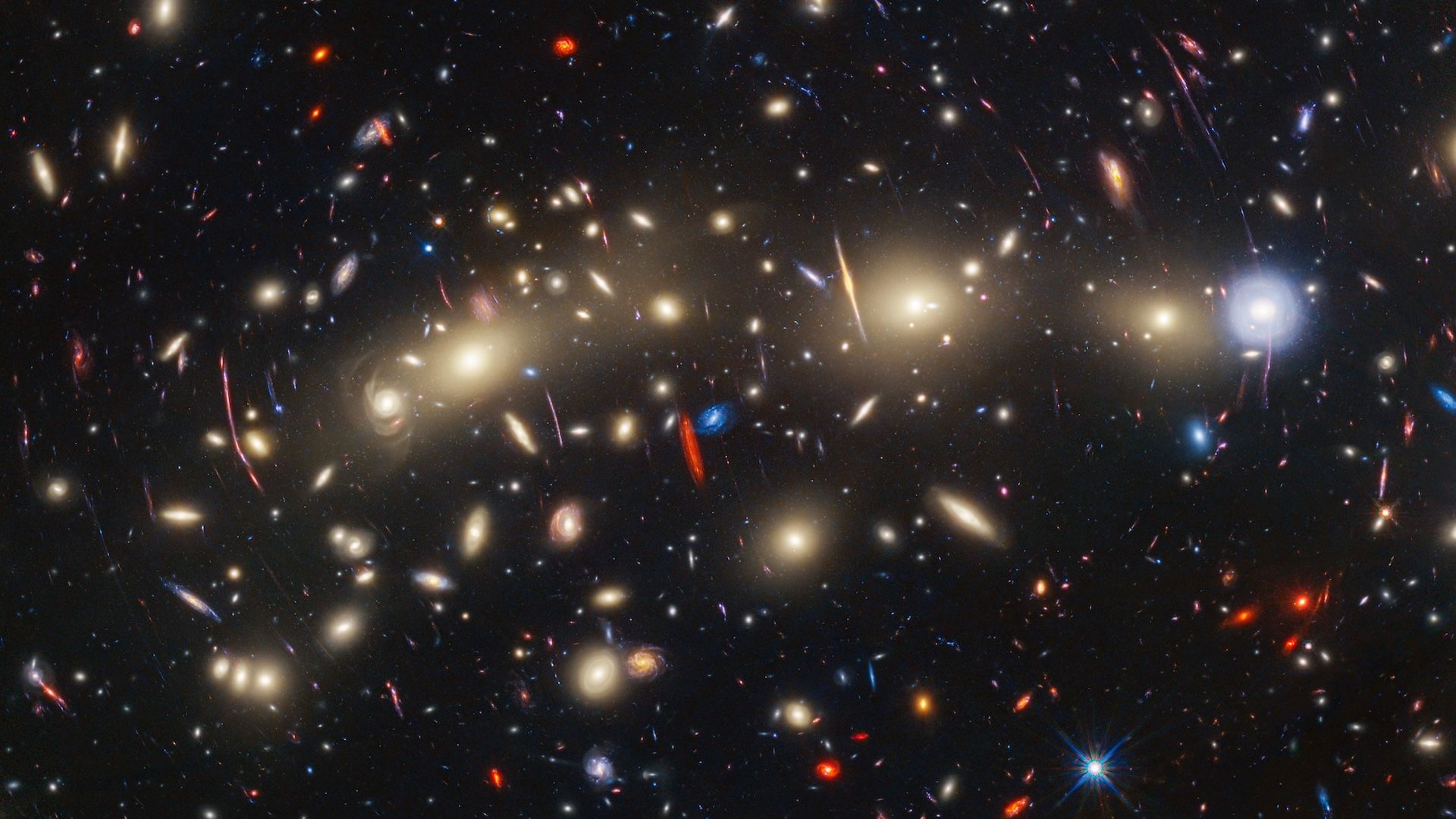

Astronomers, utilizing the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), believe they may have discovered Population III stars, some of the universe’s earliest stars, within the distant cluster LAP1-B. These stars, theorized to have formed shortly after the Big Bang, were observed thanks to gravitational lensing, where the foreground cluster MACS J0416 magnified and distorted the light from LAP1-B. The observed spectra and other characteristics of these stars align with predictions for Population III stars, suggesting the stars formed in a low-metallicity environment and had unique initial mass functions. This discovery provides insights into the early stages of galaxy formation and evolution.

Read the original article here

James Webb telescope may have found the universe’s first generation of stars, and it’s truly a mind-blowing concept. We’re talking about Population III stars, stars that likely formed shortly after the Big Bang, essentially the first lights in the cosmos. The fact that we might be getting a glimpse of these ancient objects, which have eluded us for so long, is incredible. It’s like finally finding the lost treasure of the universe’s infancy.

The implications are huge. Population III stars were made of the very first elements: hydrogen, helium, and a tiny bit of lithium. Unlike the stars we see today, they lacked the heavier elements forged in the hearts of later stars through nuclear fusion. These early stars were gigantic, incredibly hot, and burned through their fuel at a rapid rate. Their existence provides vital information about how galaxies formed and how the universe evolved from its initial state to the complex cosmos we observe now.

The hunt for these stars has always been a challenge because they are so distant and faint. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), with its unprecedented sensitivity to infrared light, is perfectly positioned to capture their faint glow. Because the light from these early stars has been stretched by the expansion of the universe, it has shifted into the infrared part of the spectrum, where JWST excels. This makes it possible to, hopefully, observe them and answer some of the fundamental questions about the universe’s earliest epochs.

It’s exciting to think about what the JWST might reveal about these stars. It’s even more exciting to think of the possibility of seeing something even more extreme. Imagine, for instance, catching a glimpse of a “Quasi-Star,” a truly bizarre theoretical object. These hypothetical objects, powered not by nuclear fusion but by a black hole at their core, are mind-boggling in their scale and properties. The idea is that these massive objects could have existed in the early universe, fueled by matter spiraling into a black hole at their centers.

The sheer size of a Quasi-Star is almost incomprehensible. Some estimates suggest they could have been so vast that the orbit of Pluto would have been contained within them! In the scenario where the core collapses, creating a black hole, the remaining stellar material wouldn’t be blown away by the energy of the explosion. Instead, the surrounding layers would absorb the blast, allowing the “star” to continue shining, albeit powered by the black hole within.

While the concept of Quasi-Stars is theoretical, they offer a glimpse into the extremes of what is possible in the universe. They represent a wild and speculative possibility of how the earliest massive objects formed. It is a bit mind-boggling how the accretion of matter around the black hole within a Quasi-Star provides the energy to power the star. This is a crucial distinction. It’s the infalling matter itself, being compressed and heated as it heads towards the black hole, that releases the energy we’d see as light and heat. It’s an incredibly efficient process, like a turbocharged version of the accretion disks we see around black holes today.

Interestingly, this whole subject also reveals how we name and categorize things in science. While “Population III” stars is the technical term, it might be more accessible and engaging to use something like “Elder Stars” to describe the first generation. It’s about more than just the name, however. It’s also important to get the definitions correct because that makes it easier for people to understand and remain interested.

The search for these stars is a testament to the power of human curiosity and our relentless pursuit of knowledge. It also reveals the scale of the known universe, which is so massive that it is often difficult to imagine. The fact that we are able to reach out and observe these objects is a remarkable feat of engineering and scientific endeavor. The universe, in all of its vastness and complexity, is a source of unending wonder.