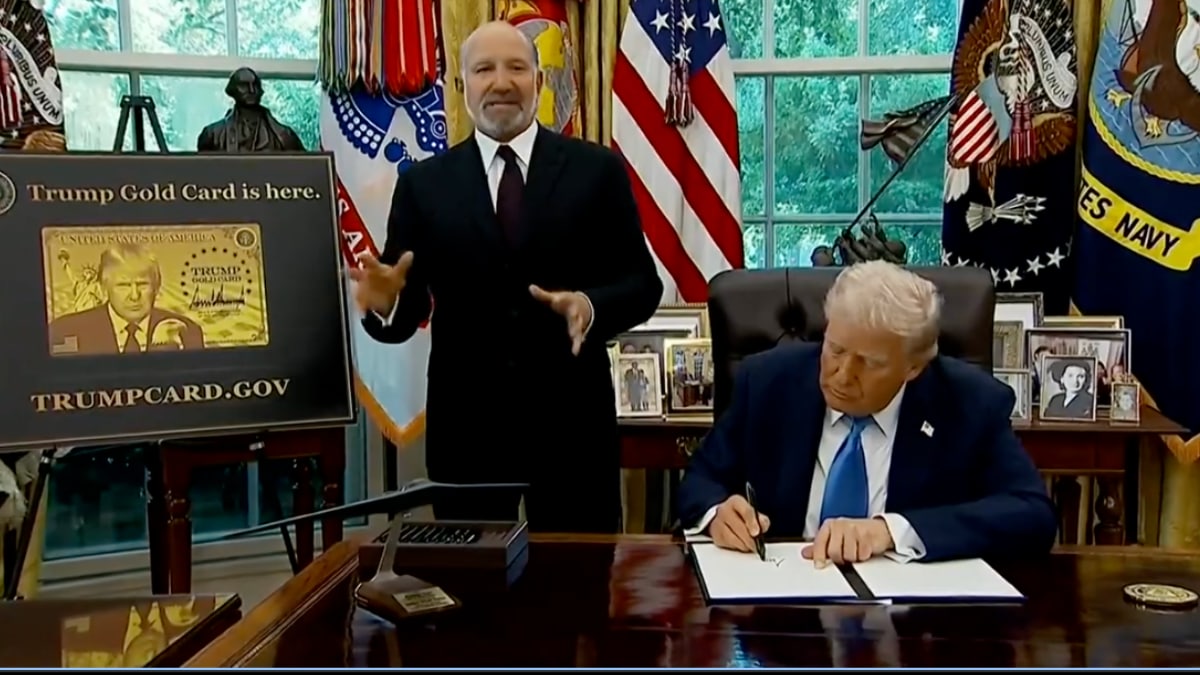

US Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick has publicly stated that India is among the countries the US aims to rectify within its trade agenda, urging them to adjust their trade practices for better access to the American market. He cited high US trade levies on Indian goods and stated that these nations must “react correctly” to the US by opening markets and ceasing actions deemed harmful. Lutnick has set specific conditions, including discontinuing purchases of Russian oil and withdrawing from BRICS, or face consequences. Trade negotiations between India and the US have resumed, but the US is looking for major changes in India’s trade and geopolitical approach.

Read the original article here

‘We have to fix India’: Howard Lutnick says New Delhi must ‘open market, stop harming’ America. It seems like someone is stepping into the ring with some strong opinions about India, and the response is, well, pretty mixed, to say the least. The idea that India needs “fixing,” specifically by opening its markets and stopping whatever “harming” they’re allegedly doing to America, has ignited a firestorm of commentary. Let’s break it down.

The immediate reaction, it appears, is a healthy dose of skepticism and a pointed question: Who appointed this person, Howard Lutnick, to “fix” anything? Many voices are saying, “Fix your own house first,” a common sentiment when another nation points fingers. The US is repeatedly asked to address its internal issues – healthcare, school shootings, political divisions, and the erosion of freedoms – before taking on the role of international fixer. This sentiment highlights the disconnect many feel between what the US preaches and what it practices.

The phrase “open market” is frequently highlighted as a call for India to change its trade policies. Some view this as thinly veiled pressure, potentially driven by specific American economic interests, such as oil and gas. There’s a suspicion that this isn’t about altruism but about securing advantages for certain US businesses, potentially at India’s expense. The history of Western powers and trade with Asia is also brought up as a cautionary tale, bringing up the British East India Company as an example to consider.

There’s a strong current of resistance to the whole idea. Some are even more direct in their criticisms, using very strong language. The core argument is that India, as a sovereign nation, has the right to determine its own course. The implication is that any attempt to force India’s hand, whether through tariffs or threats, is a misguided and potentially damaging move. The US is accused of a sense of entitlement, where it believes other countries should automatically bend to its will, which is seen as a throwback to a particularly problematic style of business and diplomacy.

A significant portion of the commentary calls out the double standard, questioning why the US is focused on India while seemingly overlooking its own flaws. The argument is that the US’s internal struggles, from economic issues to social divisions, render its attempts to “fix” another country hypocritical and ineffective. This sentiment ties into the broader critique of US foreign policy, which often faces accusations of prioritizing its interests at the expense of others.

Another common theme is the changing geopolitical landscape. The rise of China and Russia as major players complicates the picture. There’s a sense that the US pushing India could drive it into stronger alliances with these other nations, potentially backfiring and diminishing the US’s influence. The US is perceived as being alone, possibly miscalculating its impact on India’s trade practices, particularly in the face of pre-existing economic relationships.

Furthermore, the discussion delves into the practicalities of trade. Some question whether US products are even competitive in the Indian market, given factors like price and suitability. This points to a potential misreading of the Indian market. The argument is the US approach is out of touch with the realities of consumer preferences and existing trade partnerships.

Ultimately, the reaction to this idea of “fixing” India is a complex mix of cynicism, resistance, and calls for self-reflection. The article highlights skepticism of the motives, the perceived hypocrisy, and the potential negative consequences of such an approach. This reaction reflects a growing awareness of the complexities of international relations and a pushback against simplistic narratives of fixing or controlling other nations. This is a snapshot of the world’s current perception of how the US does business.