The African Union (AU) is supporting a campaign to replace the widely used Mercator map with the Equal Earth projection to more accurately reflect Africa’s size and counter the false impression of its marginalization. The Mercator map distorts sizes, making areas near the poles appear larger while shrinking Africa and South America, influencing perceptions in media, education, and policy. The Correct the Map campaign, spearheaded by advocacy groups, is urging organizations to adopt the Equal Earth map, with the AU endorsing this effort as part of its goal to reclaim Africa’s rightful place on the global stage. This initiative calls for the adoption of the Equal Earth map by global institutions, with other regions like the Caribbean Community also supporting the move as a rejection of the Mercator map’s representation of power and dominance.

Read the original article here

The African Union, it seems, is joining a chorus of voices calling for a shift away from the Mercator map projection, a move that highlights the inherent distortions in representing a three-dimensional world on a two-dimensional surface. It’s a fascinating debate that touches on issues of perception, historical context, and even a little bit of geopolitics.

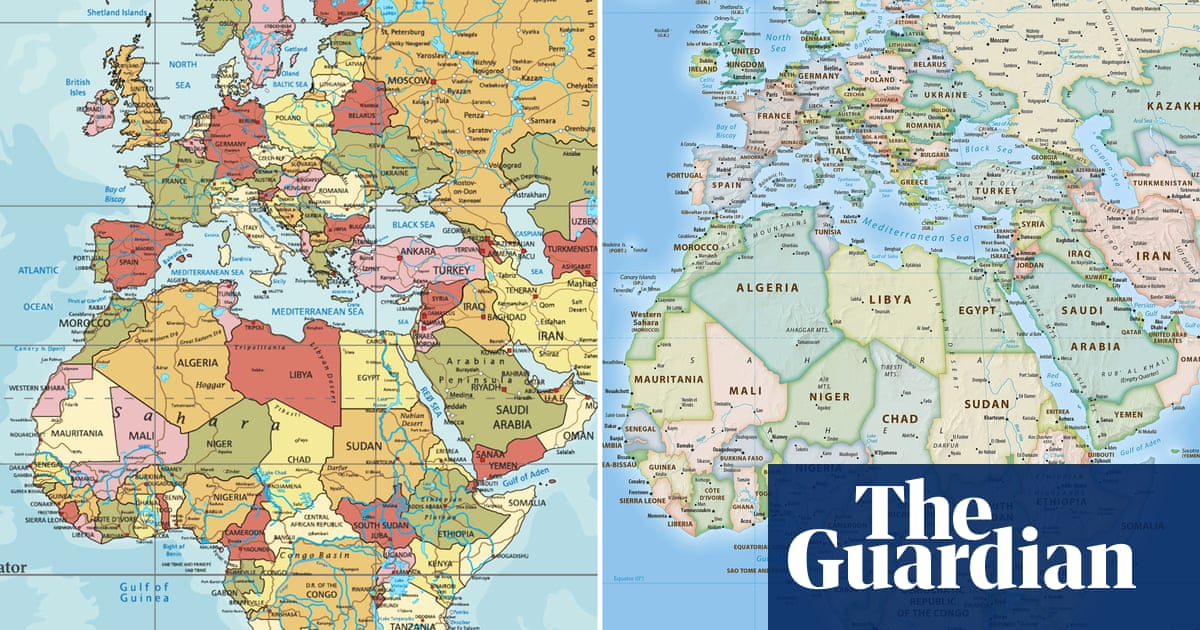

The Mercator projection, born from the needs of seafaring navigation, has been a standard for centuries. Its strength lies in maintaining accurate bearings, making it invaluable for charting courses at sea. However, this focus comes at a cost: a significant distortion of landmass sizes, especially in areas far from the equator. Greenland, for instance, appears far larger than it actually is, while Africa is comparatively diminished. This isn’t a malicious design; it’s a consequence of the mathematical process of flattening a sphere. It’s akin to trying to peel an orange and lay the peel flat—some stretching and distortion are inevitable.

There’s a common misconception that the Mercator projection was created with a deliberate bias to make certain regions appear larger than others. While the effect is undeniably present, the primary motivation for the projection’s design was practical, not political. Its prevalence in navigation solidified its place as the default map, but this doesn’t mean that it’s the most suitable for all purposes. Today, with advancements in mapping technology and a broader understanding of global geography, the limitations of the Mercator projection are becoming increasingly apparent.

The African Union’s call is, in essence, a request for a more balanced and accurate representation of the world. It’s not that Africa is “shrunk,” as some might put it. Rather, other landmasses, particularly those closer to the poles, are inflated. This distortion can lead to a skewed perception of relative sizes and potentially influence how we understand global power dynamics. Replacing the Mercator projection wouldn’t magically solve any problems, but it is an important step to achieve greater equality and understanding.

Of course, there are many other map projections to choose from, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. The Azimuthal Equidistant projection, which the UN flag uses, is one option, although it too presents its own distortions, particularly in the southern continents. Some maps prioritize preserving area, while others focus on maintaining shape or distance. The “Equal Earth” projection, for example, is gaining popularity, offering a more realistic depiction of relative landmass sizes. The Robinson projection strikes a balance between shape and area, making it another possible contender.

This push for change shouldn’t be dismissed as trivial. Maps are not just tools for navigation; they’re also powerful instruments of communication and influence. The way the world is presented can shape our perceptions and attitudes. Changing the map projection can be a symbolic act of asserting a more equitable perspective. It challenges the historical dominance of a projection designed for a specific purpose and invites us to consider a more inclusive representation of our world.

The debate has also sparked some humorous reactions, with some people joking about what this might mean for Trump and his perceived fascination with Greenland. In all seriousness, it serves as a reminder that maps, like all representations of reality, are constructed and can be subject to bias, even if unintentional.

Ultimately, the African Union’s stance highlights the importance of critical thinking and awareness of the choices involved in mapmaking. While the Mercator projection served its purpose for centuries, the time may have come for a change that reflects a more balanced and representative understanding of the world.