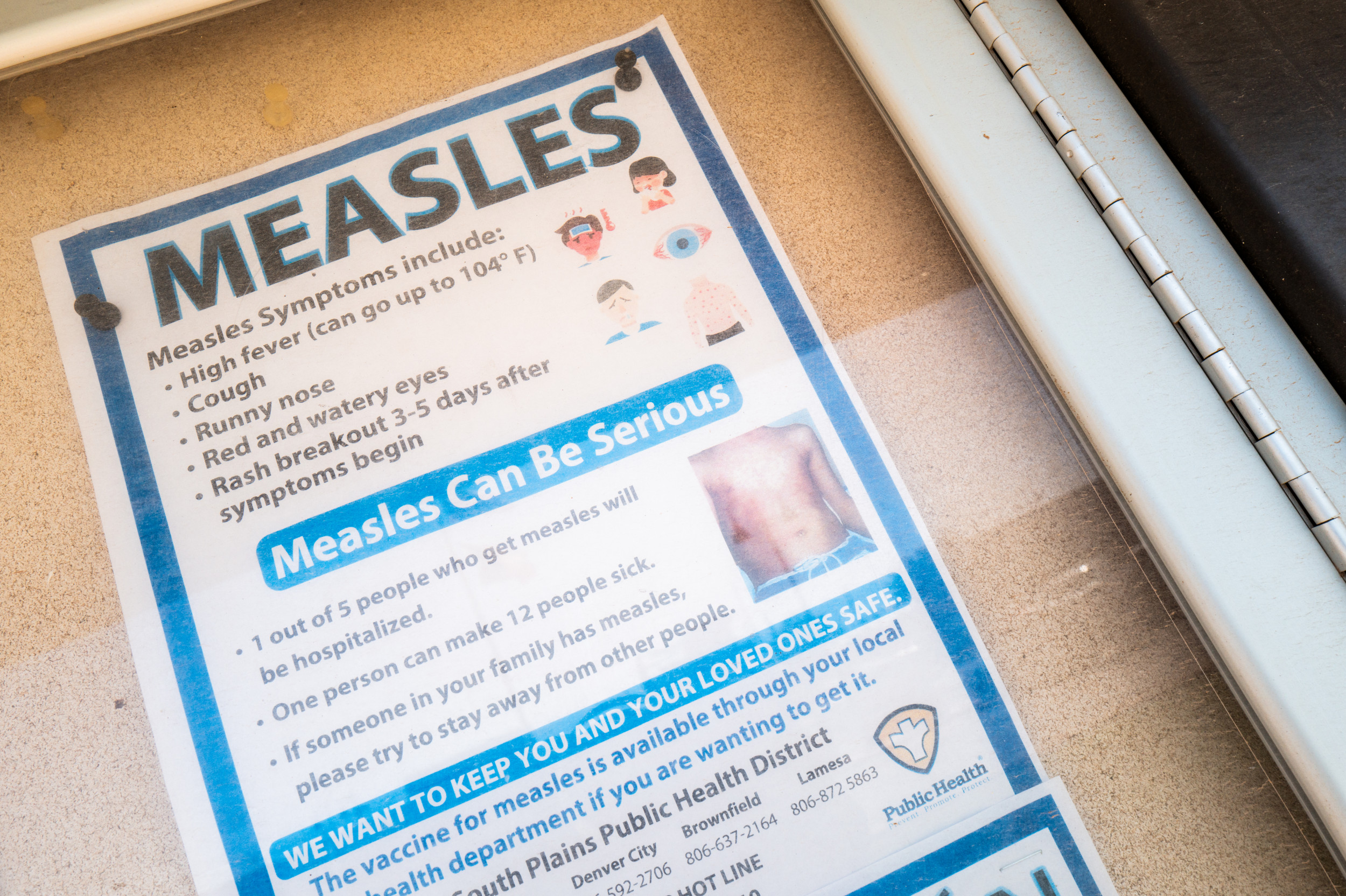

The United States is experiencing its worst measles outbreak since the disease was declared eliminated in 2000, with over 1,277 confirmed cases reported by early July. This figure surpasses the peak year of 2019, leading to increased hospitalizations and putting a strain on health care systems. The majority of cases are concentrated in West Texas, originating from an undervaccinated community, and are occurring amid declining childhood vaccination rates nationwide. Public health officials are implementing intensified vaccination campaigns and contact tracing to combat the spread, while monitoring international travel patterns to prevent further outbreaks.

Read the original article here

US measles cases at an all-time high after disease “eliminated” – Well, isn’t this a pickle? It’s a bit jarring to hear that measles cases in the US are spiking, especially after we thought we’d essentially kicked the disease to the curb. The whole situation feels like a bad rerun of a history lesson we really shouldn’t need to revisit.

The root of the problem, as I gather, seems to stem from the rejection of vaccines. It’s the same story you hear about other public health issues, playing out again: a combination of misinformation, distrust in experts, and a general skepticism towards science. It’s a bit like watching a slow-motion train wreck, where you know the outcome but can’t quite stop it.

And the irony is almost too much to bear. We’re talking about a disease that was once a major cause of illness and death, and we had a safe and effective way to protect ourselves. But here we are, with parents choosing not to vaccinate their children, and now we are seemingly paying the price. There’s a feeling of helplessness and frustration because we have the tools to prevent this, yet we’re not using them effectively.

The implications reach far beyond just the individual cases of measles. When vaccination rates drop, it compromises what’s known as “herd immunity.” It means that vulnerable individuals, like infants too young to be vaccinated or people with certain medical conditions, become more susceptible to the disease. It’s not just about personal choice anymore; it’s about a community’s collective health.

One of the more striking things is the political aspect to this. The issue of vaccinations, and science in general, has become strangely politicized. Certain ideologies seem to align with distrust in scientific consensus, and the consequences of this are now, sadly, visible. It makes it all the more challenging to have a rational, science-based conversation about public health when it’s mixed up with political agendas and misinformation.

It is also important to note that in some cases these issues can come from people who we respect. We may see that people who are in charge of important information are not sharing factual information, which can be very frustrating. When you have influential figures spreading false claims about vaccines, it creates a breeding ground for doubt and skepticism.

Of course, it’s not just about politics. It’s about the spread of misinformation. The internet has become a wild west of health information, with all sorts of unverified claims circulating. It can be tough for people to distinguish between credible sources and those promoting dubious ideas.

Another concerning part is the rise of “alternative cures” and skepticism towards modern medicine. It’s almost as if people are more afraid of the “chemicals” in vaccines than they are of the diseases themselves. It’s worth mentioning here that our health care systems may not be great, with lack of resources and no universal health care. However, that should not stop us from vaccinating our children, or ourselves, to stop the spread of dangerous diseases.

Then there’s the feeling of anger and frustration. The level of scientific ignorance and conspiracy theories can be truly astounding. The idea of having to revisit a disease like measles because of these beliefs is disheartening.

Looking ahead, there is a need for a serious reevaluation of how we communicate about public health. It’s crucial to promote accurate information, address vaccine hesitancy, and build trust in medical professionals. We need to find ways to bridge the divides and find common ground in a shared commitment to public health.