Tulsa, Oklahoma, is allocating $105 million in reparations for the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, a sum raised by a private trust. The “Road to Repair” plan, spearheaded by Tulsa’s first Black mayor, focuses on community redevelopment, including housing and cultural preservation, rather than direct payments to descendants. Funding will be managed by the Greenwood Trust, named after the destroyed Black Wall Street. This initiative marks a significant step toward addressing the lasting economic and social harms of the massacre, a largely hidden chapter of American history.

Read the original article here

Tulsa, Oklahoma, is planning to allocate over $105 million in funds aimed at addressing the lasting consequences of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. This significant investment, spearheaded by Tulsa’s first Black mayor, Monroe Nichols, is focused on community redevelopment initiatives within the city.

The plan intentionally avoids direct financial compensation to descendants of the victims or the two surviving witnesses of the horrific event. This decision reflects a prioritization of community-wide improvements over individual payouts. The rationale behind this approach warrants further consideration; perhaps a broader impact was deemed more effective than individual reparations.

Many question the wisdom of labeling this significant investment as “reparations,” arguing that the term could generate unnecessary backlash. A less controversial label, such as “community revitalization effort,” might have garnered more widespread support. This highlights the politically charged nature of the word “reparations” and the careful consideration needed when selecting such terminology.

The omission of the Tulsa Race Massacre from many Oklahoma history curriculums underscores the historical suppression of this tragic event. This deliberate lack of inclusion in educational materials has contributed to a widespread unawareness of the massacre among younger generations, showcasing a systemic failure in accurately representing the full history of the state. It’s a stark reminder of how easily painful chapters of history can be buried, leaving future generations uninformed.

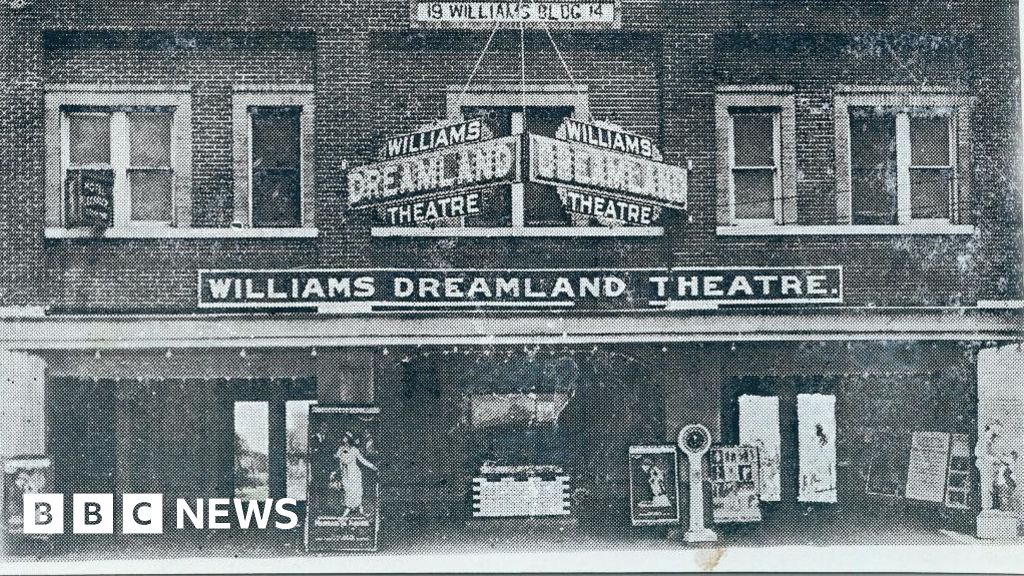

The scale of the tragedy, often termed America’s “hidden” massacre, compels a critical evaluation of the proposed $105 million allocation. This amount represents a substantial investment, but some argue it’s insufficient given the economic devastation inflicted upon the Greenwood District, also known as Black Wall Street. The complete destruction of an entire economy and generations of accumulated wealth cannot easily be measured or quantified. A full accounting of the long-term economic losses would likely dwarf this figure, leading to the question of whether the investment, while significant, is truly commensurate with the damage done.

The deliberate suppression of the Tulsa Race Massacre, the intentional underinvestment in the affected area, and the calculated practice of redlining all represent historical injustices that continue to reverberate through the generations. This systemic discrimination illustrates how economic and social policies can be weaponized to disenfranchise and impoverish entire communities.

The city’s plan to invest $60 million in rebuilding and revitalizing the north side of Tulsa represents a significant step toward rectifying the past harms. However, the issue also brings forward discussions on the broader implications of historical injustices and the appropriate mechanisms for redress. The sheer scale of the destruction and its systemic nature is beyond mere monetary compensation; it requires a comprehensive approach that not only addresses economic disparity but also the deep-seated trauma experienced by the community.

The absence of the Tulsa Race Massacre from widespread knowledge highlights the necessity for comprehensive historical education. The deliberate omission of this significant event from mainstream narratives suggests a pattern of selective historical recollection, prioritizing certain events while minimizing others, which often mirrors existing power dynamics. This raises important concerns about the accuracy and completeness of historical narratives generally.

Discussions about the Tulsa Race Massacre often bring up the concept of reparations. Some believe that this term is essential to acknowledge the historical atrocity, while others view it as unnecessarily inflammatory. The choice of terminology itself becomes a point of contention, revealing the inherent complexities involved in navigating conversations about historical trauma and societal redress.

The significant financial awards in some recent civil cases highlight the perceived value of human life in legal contexts. Comparisons to settlements in other wrongful death cases highlight the complexities of assigning monetary value to historical injustices, especially considering the far-reaching and multigenerational consequences of the Tulsa Race Massacre. It’s not simply a matter of replacing lives lost, but accounting for the generational wealth destroyed, the stifled opportunities, and the ongoing psychological trauma.

Despite the passage of over a century, the two surviving victims of the Tulsa Race Massacre, Viola Fletcher and Lessie Randle, are still alive, adding a profound dimension to the reparations discussion. Their continued existence serves as a stark reminder of the ongoing legacy of this tragedy, demanding not just economic but also emotional and social reconciliation. Their advanced age only underscores the urgency of addressing this historical injustice. The fact that these individuals are still alive adds a layer of urgency and poignancy to the ongoing discussion surrounding reparations.