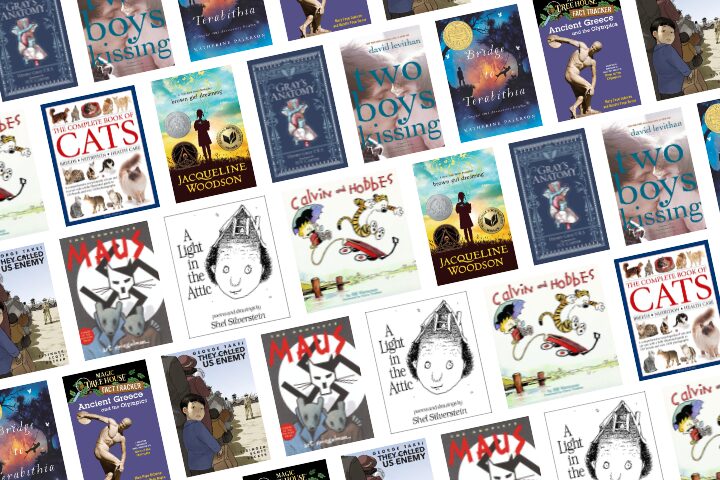

Hundreds of books have been removed from Tennessee school libraries due to an amended “Age-Appropriate Materials Act,” leading to the purging of titles across multiple counties. The law’s broad definition of inappropriate content, including nudity or depictions of sexual conduct, allows for the removal of books based on excerpts without considering context. This has resulted in the banning of diverse works, ranging from children’s literature to Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novels and historical accounts, impacting students’ access to a wide range of perspectives and educational materials. The inconsistent application of the law across districts highlights the challenges and concerns surrounding this widespread censorship.

Read the original article here

Fahrenheit 451, a novel exploring the dangers of censorship and book burning, is not actually banned everywhere, but attempts to remove it from libraries and schools are causing quite a stir. The irony, of course, is that banning a book about banning books seems profoundly counterintuitive.

This situation highlights a broader issue: the increasing attempts to control access to literature, often driven by ideological agendas. Many see these actions as a direct threat to freedom of thought and expression, values that underpin a democratic society. The sheer absurdity of banning such books is a point consistently raised. For instance, the idea of banning a children’s book like *Calvin and Hobbes* is met with disbelief and outrage. It’s seen as evidence of a regressive mindset, one that actively seeks to limit access to information and critical thinking.

The debate also sparks reflection on the role of literature, especially in education. High school students reading *1984* or *Brave New World* in the current political climate is considered especially pertinent. These novels provide valuable context for understanding the power structures and societal pressures that shape our world. The removal of such texts from curricula is viewed as a severe disservice to young people.

The reactions to these book removal attempts are not uniform. Some view them as examples of curation, a necessary aspect of library management. However, many strongly disagree, arguing that removal from libraries, especially when driven by political pressure, constitutes de facto censorship. The debate centers on the difference between curation and suppression. Is simply not stocking a certain title the same as a government-enforced ban? The distinction is crucial to understanding the implications of this issue.

The idea that banning books makes them more popular is frequently mentioned. The very act of trying to suppress a book often generates significant interest and increases its readership. Parents are proactively buying books they feel might be banned next and gifting them to friends’ children. This creates a cycle: banning books ironically fuels their popularity, making the attempts at suppression self-defeating.

The arguments often take a strongly partisan tone. Many believe that the individuals advocating for book removals are not true conservatives, but rather fascists or white Christian nationalists, intent on shaping societal narratives to conform to their own views. The perceived hypocrisy of such actions, particularly given their claims to valuing freedom, is a frequently mentioned point of contention.

Beyond the specific titles mentioned, the broader discussion touches on the chilling effect of censorship. The fear of future bans creates a climate of self-censorship, where authors and publishers might avoid controversial themes for fear of reprisal. This stifles creativity and the free exchange of ideas, a critical element of a healthy society. The long-term consequences of such actions are viewed with considerable concern.

The availability of books online offers a potential countermeasure. Websites like the Internet Archive provide access to countless books, making them harder to completely suppress. This underlines the difficulty, perhaps impossibility, of completely controlling access to information in the digital age. Yet, the attempt itself remains a cause for deep concern. The ongoing tension between preserving freedom of access to information and managing what materials are made available in public libraries remains a significant challenge to be addressed.