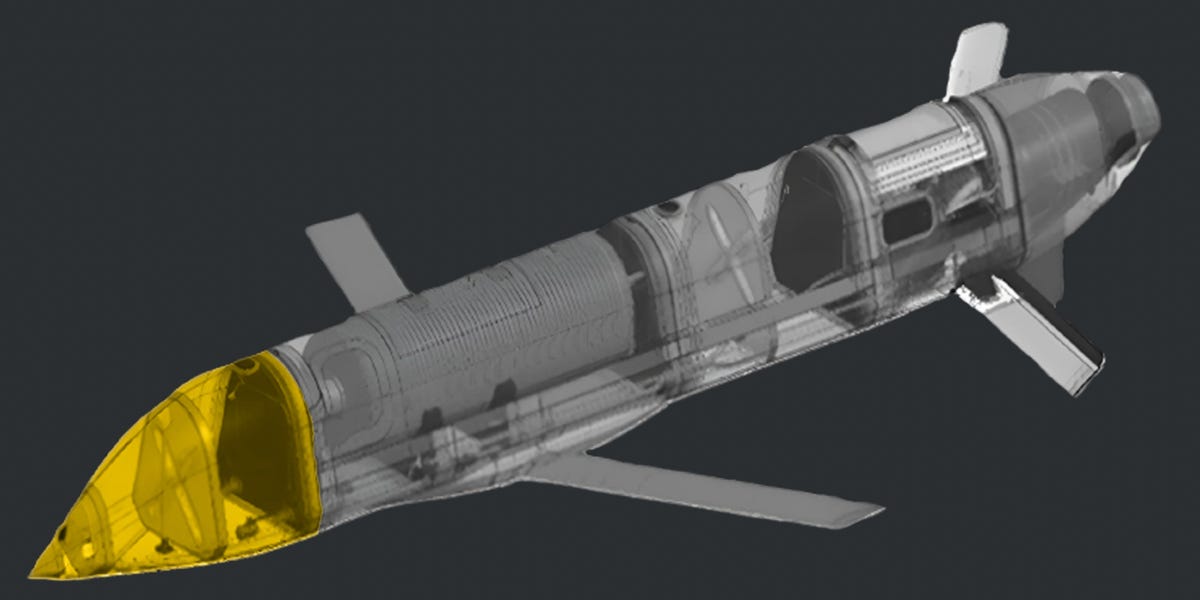

Ukraine’s Defence Intelligence agency (GUR) revealed the components of a new Russian S8000 “Banderol” cruise missile, identifying parts from the US, Japan, South Korea, and potentially Australia. This discovery highlights Russia’s circumvention of sanctions imposed after its invasion of Ukraine, despite these countries’ export controls and aid to Ukraine. The missile, launched from an Orion drone or Mi-28N helicopter, boasts a 310-mile range and unique maneuverability. GUR’s analysis underscores the need for increased scrutiny of parts exports to prevent their diversion to Russia’s military industry.

Read the original article here

Russia’s new drone-launched cruise missile, dubbed the “Banderol,” has reportedly been used in attacks on Odesa. Ukrainian intelligence claims to have recovered and analyzed one of these missiles, revealing a startling discovery: it’s packed with components sourced from countries allied with Ukraine.

This revelation raises significant questions about the effectiveness of international sanctions on Russia. The sheer presence of parts from the US, Japan, and South Korea within a sophisticated weapon system suggests a serious loophole in the enforcement of these measures. It’s not just about a few high-profile, easily identifiable components; it’s about the many smaller parts, the microchips, servos, and other components that are ubiquitous in modern electronics and easily obtainable through various channels.

The claim that the missile contains parts from these allied nations seems to challenge the notion of effective sanctions. While the thought of entire, easily traceable units like “Toshiba missile guidance computer chip 1” being used might seem simple, the reality involves millions of smaller, generic components. A car alone contains hundreds of servos; accelerometers, common in phones, cost mere pennies. Generic ARM chips used in countless applications also find their way into various technologies, including missile guidance systems. This points to the challenges in tracking and controlling the flow of dual-use technology in a globalized world.

The Ukrainian claim underscores the difficulties in preventing the acquisition of these components by sanctioned entities. It highlights the complex web of supply chains and the ingenuity of those seeking to evade sanctions. It suggests that the current approach to sanctions may need to be reviewed, given its apparent ineffectiveness in this high-stakes scenario. While the intention is clear – to cut off Russia’s access to vital components – the reality shows that the flow of parts continues, even when specific items are listed under sanctions.

The response from Ukraine regarding the missile’s origins has sparked debate. While some believe publicizing this information is a strategic move, perhaps to generate greater pressure on allied nations to tighten export controls or to rally international support, others question the wisdom of such a public accusation. Accusing specific countries like Japan and South Korea of directly contributing to Russia’s war machine is a strong step. Such accusations, whether accurate or not, could damage international relations and undermine cooperative efforts to curb the conflict. There’s a valid concern that such pronouncements could even backfire, potentially hindering future cooperation on containing Russia’s military capabilities.

This situation also exposes the inherent challenges in tracing the origins of components used in weapons systems. The sheer volume of parts, the complexity of global supply chains, and the potential involvement of middlemen and shell companies make it extremely difficult to effectively monitor and control the flow of goods. While batch numbers and quality control measures offer potential avenues for tracing, the process is far from foolproof, especially when dealing with large-scale smuggling operations.

The issue highlights a double standard often debated in conflict zones. When a sanctioned country uses weapons assembled from internationally sourced parts, the blame is placed squarely on the sanctioned entity; however, when the opposing side uses weaponry supplied by its allies, the narrative shifts, often focusing on the moral implications or strategic alliances. This inequality in framing further complicates the situation and raises questions about the ethical and geopolitical implications of supplying weaponry to either party during times of war.

Furthermore, the long-term implications of this supply chain vulnerability should not be overlooked. The military-industrial complex’s continuous need for funding, estimated at around $50 billion annually for the US alone, creates an environment where profit often overshadows ethical concerns. This perpetuates a cycle of conflict, undermining efforts to achieve a peaceful resolution, as the financial incentives for prolonging the conflict outweigh those for achieving peace. This underscores the need for a wider, more coordinated international effort to address the root causes of conflict and to establish more robust mechanisms for controlling the flow of dual-use technology. The current approach appears inadequate in effectively preventing its use in conflicts like the one unfolding in Ukraine. The scale of the problem, particularly with readily available, mass-produced components, presents a massive challenge that will require a more comprehensive and nuanced strategy to address.