Hundreds of Nazi-related documents and membership cards, including propaganda materials and photographs, were recently discovered in Argentine Supreme Court archives. These items, shipped from Tokyo in 1941 and initially flagged by customs officials, were part of a case investigated by a congressional commission concerned about potential threats to Argentina’s neutrality during World War II. The materials, which include membership booklets from the “Unión Alemana de Gremios,” have been secured for preservation and analysis to determine their relevance to Holocaust investigations and the post-war influx of Nazis into Argentina. Supreme Court Chief Justice Horacio Rosatti has ordered a full inventory of the newly found archive.

Read the original article here

Nazi documents, hundreds of them in fact, have recently been unearthed in the Argentine Supreme Court archives. These documents, discovered during the relocation of files for a planned museum, were tucked away in boxes in the basement of the Palace of Justice. The find itself is remarkable, highlighting the enduring presence of Nazi influence, even within the seemingly unlikely setting of a national judicial archive.

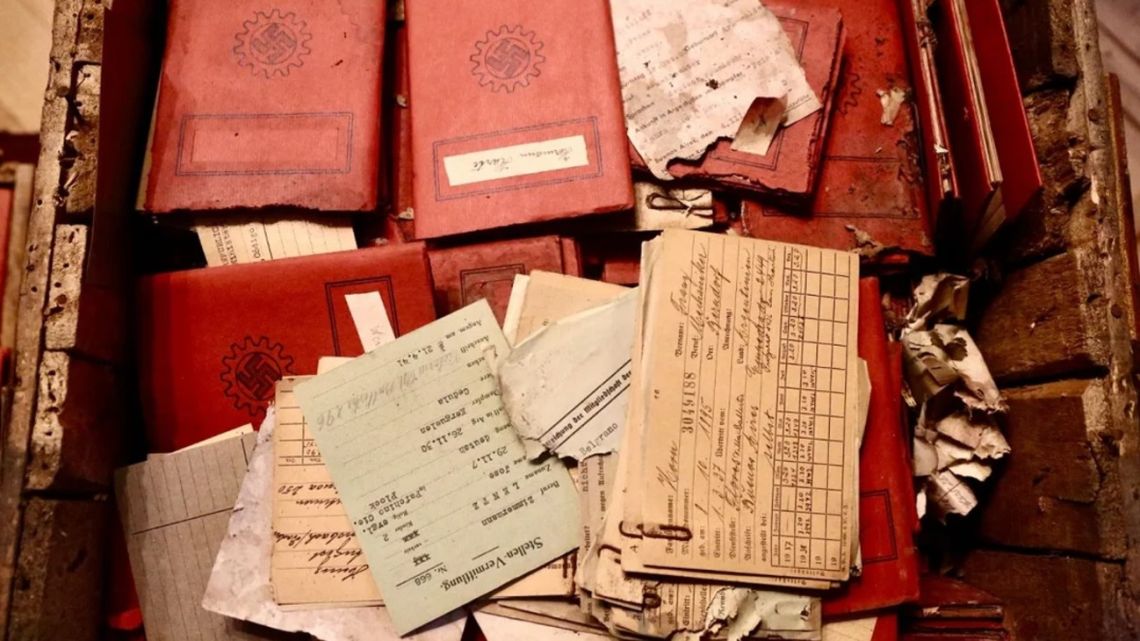

The discovery, made last Friday, May 9th, has led to the immediate securing of seven boxes containing the materials. The Supreme Court has ordered their classification, documentation, and preservation. This careful process underscores the significance of the find and the Court’s recognition of its potential historical importance. Initial assessments suggest the materials consist of propaganda from Hitler’s regime, designed to disseminate Nazi ideology within Argentina.

Among the items discovered are photographs and hundreds of membership booklets from the “Unión Alemana de Gremios,” clearly bearing swastikas. The condition of the documents varies; some are severely deteriorated, while others are remarkably well-preserved. The initial inspections, conducted in the presence of key figures including the Supreme Court Chief Justice, a Chief Rabbi, and Holocaust museum director, hint at the gravity of the situation and the multi-faceted expertise brought to bear on the evaluation.

The provenance of these documents is equally compelling. Records indicate the materials arrived in Argentina on June 20, 1941, aboard the Japanese ship Nan-a-Maru, sent from the German Embassy in Tokyo. Although initially declared as “personal effects,” customs officials rightly flagged the shipment and alerted the then-foreign minister. The subsequent investigation by a special congressional commission suggests an early understanding of the potential implications of the material’s presence.

This commission, now defunct, intervened to examine whether the contents posed a threat to Argentina’s wartime neutrality. Their investigation, conducted in 1941, uncovered membership booklets, postcards, and photos bearing Nazi propaganda. A subsequent attempt by the German Embassy to reclaim the shipment was thwarted by a federal judge who ordered its seizure. The documents’ subsequent transfer to the Supreme Court in September 1941 reflects their judicial significance, even then.

Remarkably, the boxes remained in judicial custody for over eighty years until their recent discovery. The Supreme Court Chief Justice has ordered the preservation of these materials and the creation of a comprehensive inventory to determine if they shed new light on the Holocaust or Nazi financial networks. This initiative reflects a commitment to fully understanding the historical context and potential implications of this remarkable find.

The discovery holds significant implications given Argentina’s historical role as a refuge for numerous Nazi criminals after World War II. Figures like Josef Mengele and Adolf Eichmann, along with countless collaborators, sought sanctuary within Argentina’s borders. This historical context lends even greater weight to the potential significance of these newly discovered documents.

The recent declassification of other files earlier this year by the Argentinian government, aimed at aiding the Simon Wiesenthal Center’s Holocaust investigations, suggests a concerted effort to confront Argentina’s complex past. The sheer estimated number of Nazis who passed through or settled in Argentina after the war underscores the magnitude of the task. This discovery adds another significant piece to this complex historical puzzle. The recent discovery underscores a need for a thorough examination of what these materials might reveal about the period and the extent of Nazi influence in Argentina. The long-term preservation of the documents and the subsequent research will hopefully illuminate a significant part of Argentina’s past, and potentially reveal new aspects of the Holocaust and the activities of Nazi fugitives in the post-war years. The careful and comprehensive approach taken by the Supreme Court suggests a commitment to transparency and a desire to confront the difficult aspects of this history.