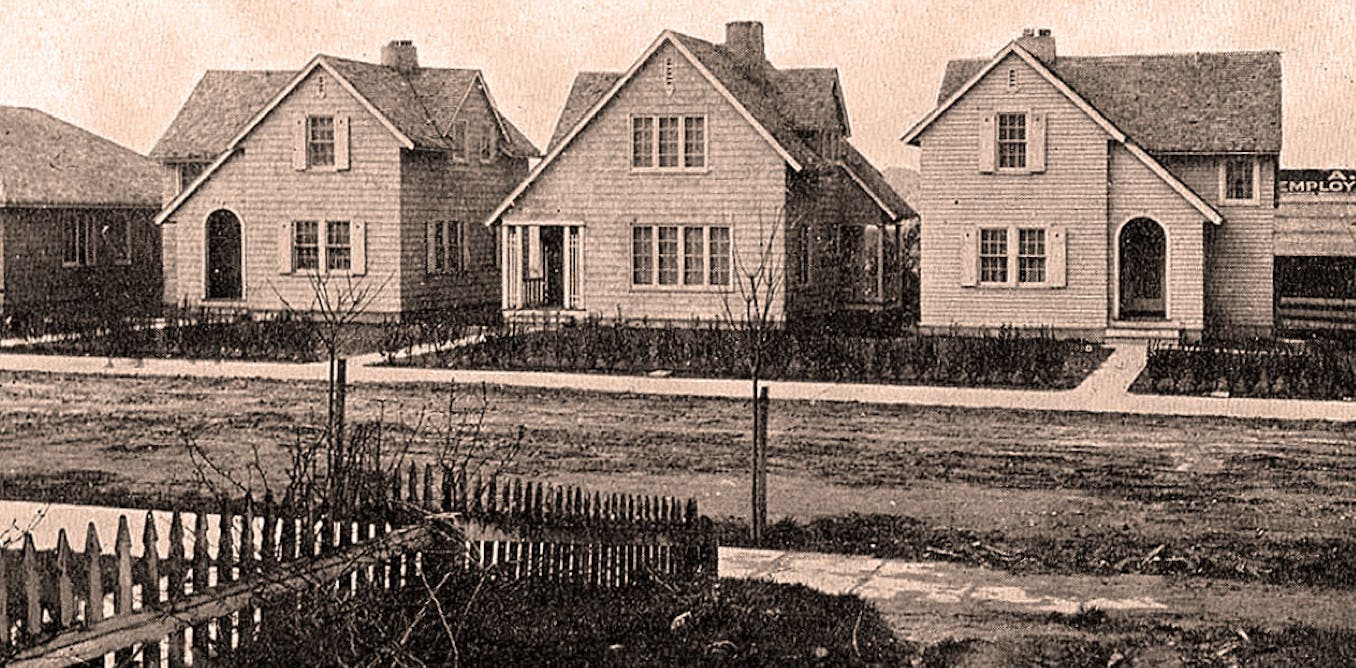

In response to World War I, the U.S. government created the United States Housing Corporation, which, between 1918 and 1920, built over 80 planned communities across the nation to house nearly 100,000 workers. These developments, incorporating principles of the Garden City movement, prioritized not just shelter but also community design, including parks, schools, and shops, and emphasized single-family homes, many of which were eventually sold to residents. The Corporation also established national planning and design standards, influencing subsequent housing projects and urban planning practices. Despite its short lifespan, the initiative’s impact on American housing and urban development remains visible today.

Read the original article here

Believe it or not, there was a time when the US government actively built homes for working-class Americans, and these weren’t just any homes; many were considered beautiful and functional. This wasn’t a fleeting moment, but rather a significant period reflecting a different approach to national priorities and the role of government in citizens’ lives. It was a time when addressing a housing crisis wasn’t a partisan issue, but a shared national concern demanding a governmental solution. The scale of the undertaking was enormous, encompassing entire neighborhoods and communities built to accommodate the needs of a growing workforce, especially evident during and after World War II.

Believe it or not, these government-funded housing projects were not only successful in providing shelter, but also in shaping communities. Some of these neighborhoods, built to house shipyard workers and other essential personnel, still stand today, a testament to the durability and quality of the construction. These homes weren’t just places to live; they represented a sense of community and stability, fostering a shared identity among residents. The impact extended beyond mere bricks and mortar; the government’s investment fostered a sense of optimism and national purpose that resonated with the working class.

Believe it or not, the government’s involvement in housing extended beyond simply constructing homes. Programs like the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) played a crucial role in making homeownership more accessible to working-class families, providing mortgages and loan guarantees that otherwise would have been unattainable. This enabled veterans returning from war and other deserving citizens to secure their own homes, representing a significant step towards the American dream of homeownership. The impact was widespread, reaching numerous communities across the nation and contributing to a sense of prosperity and national progress.

Believe it or not, the historical precedent of government-led housing initiatives points to a stark contrast with the current situation. The nostalgic reflection on this era reveals a desire for a renewed commitment to affordable housing initiatives. There’s a yearning for a time when the government played a more active role in solving societal problems, a role that many believe has been diminished in recent times. The memories of these homes are deeply ingrained in the collective memory, often associated with a feeling of security, community, and opportunity.

Believe it or not, the success of past government-led housing initiatives isn’t just a matter of historical interest; it’s a crucial lesson for the present. Many believe that the decline in affordable housing options and the widening gap between the rich and poor are directly linked to the diminished government role. They advocate for a return to policies that prioritize affordable housing and social well-being, rather than purely economic growth. The argument suggests that a government focused on the needs of its citizens, rather than the interests of corporations, is essential for creating a more equitable and just society.

Believe it or not, the narrative surrounding these past housing initiatives isn’t without its complexities. While some laud them as models of effective government intervention, others point to the discriminatory practices that marred many of these programs. Redlining, for instance, systematically denied access to housing based on race and ethnicity, perpetuating racial inequality. The historical context reveals a deeply flawed system, one that, despite providing housing for many, failed to deliver on its promise of equal opportunity for all. This serves as a crucial reminder that the mere existence of government programs isn’t enough; fair and equitable access is critical for true success.

Believe it or not, the longing for the “good old days” when the government built beautiful homes for working-class Americans is not simply a romanticized view of the past. It reflects a genuine desire for a more just and equitable society, one where the government plays a proactive role in addressing fundamental needs like housing. The lessons learned from both the successes and failures of past initiatives are invaluable in shaping future policies. Addressing the current housing crisis requires a multifaceted approach that learns from the past, confronts its shortcomings, and prioritizes equity and inclusivity. The dream of affordable, quality housing for all should not remain a nostalgic memory but a tangible goal for the future.

Believe it or not, the echoes of the past continue to resonate in the present-day debate on affordable housing. Many current proposals for affordable housing initiatives seek to learn from past successes while avoiding past mistakes. The focus on scattered-site housing development, rather than large-scale projects, is a notable shift. This strategy aims to integrate affordable housing into existing communities, preventing the creation of isolated and potentially marginalized neighborhoods. The renewed focus on equitable access and anti-discriminatory practices underscores a commitment to creating truly inclusive housing solutions. The past serves not as a blueprint to be blindly followed, but as a guidepost, pointing toward a future where housing is viewed not as a commodity, but as a fundamental human right.