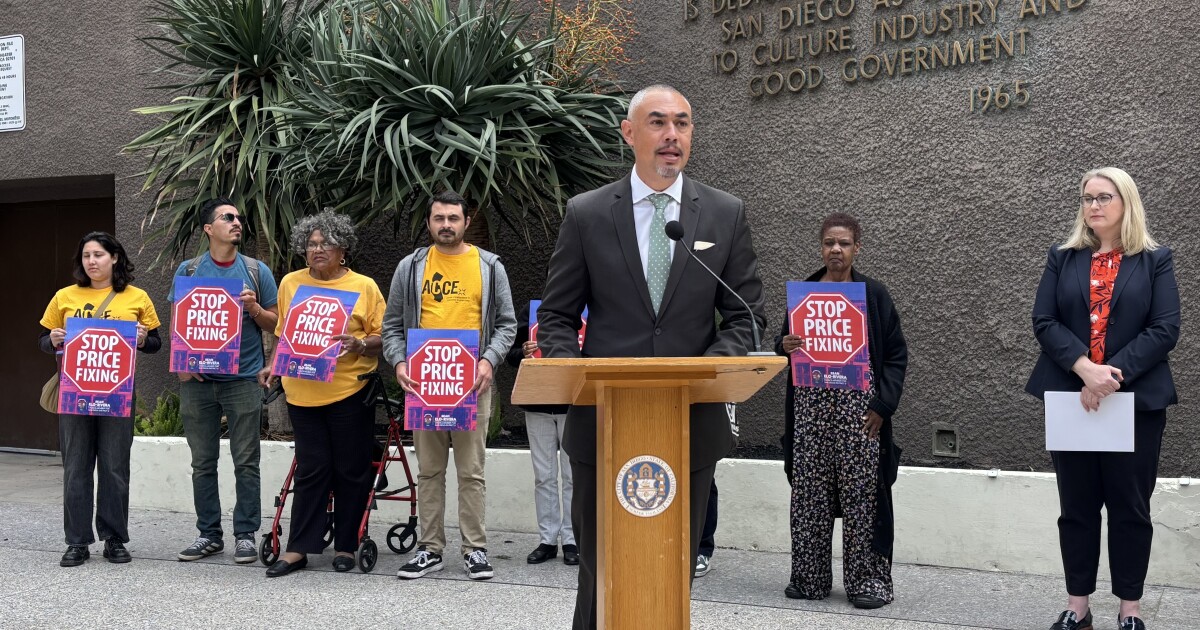

San Diego’s City Council passed an ordinance, 8-1, prohibiting landlords from using private data-driven algorithms to determine rental prices. This measure, targeting companies like RealPage, aims to prevent potentially anti-competitive practices currently under legal challenge. The ordinance, while excluding algorithms using public data, intends to protect tenants from unfair rent increases and is enforceable through tenant lawsuits. However, opponents argue the ordinance is overly broad and could hinder the development of new housing.

Read the original article here

San Diego City Council’s recent ban on landlords using algorithms for “price fixing” presents a complex issue with significant hurdles to enforcement. While the intention—to prevent landlords from colluding to artificially inflate rents—is laudable, the practical application faces considerable challenges.

The ordinance grants tenants the right to sue landlords for violations, but proving the use of a banned algorithm will be incredibly difficult. Landlords could easily revert to pre-AI methods of informally gathering competitor pricing information, whether through social gatherings or direct calls, making it nearly impossible to distinguish between algorithmic and manual price setting. The sheer effort required to prove that price setting was algorithmic rather than manual would be substantial and perhaps impossible.

The ordinance’s exclusion of algorithms using publicly available data like Zillow listings further complicates matters. Landlords can easily replicate the functionality of any banned algorithm by simply using publicly available information and manually entering it into a spreadsheet. This renders the ban essentially unenforceable against landlords who are determined to circumvent it.

The underlying issue of housing affordability transcends algorithmic price-setting. Many argue the root cause lies in insufficient housing supply due to restrictive zoning laws and NIMBYism (Not In My Backyard) attitudes. Restricting the density of housing through restrictive zoning policies, for example, exacerbates scarcity and drives up prices, irrespective of whether algorithms are involved. While an increase in supply might not completely resolve the issue, it is crucial to consider that the problem exists on a much larger scale than the mere use of an algorithm.

The argument that landlords simply replicate prior practices is valid. Before AI-driven pricing software existed, landlords frequently informally shared pricing information, either directly or indirectly. The AI tools largely automated this process and even helped reduce manpower. The ban, therefore, may simply shift the burden back to manual labor, potentially increasing operating costs for landlords, who may pass those increases on to renters. The net outcome remains essentially unchanged. Alternatively, landlords might use external mystery-shopping services, which can be expensive and would also lead to increased costs and rents.

The definition of “price fixing” itself is vague and ambiguous. Merely checking competitor prices, a common business practice, could be interpreted as price fixing, regardless of whether it uses an algorithm. Furthermore, the lack of specific enforcement mechanisms and auditing procedures raises concerns about the ordinance’s practical efficacy. The ordinance leaves room for subjective interpretation and offers little guidance on how to effectively determine when illegal collusion is happening.

The potential for loopholes and unintended consequences is also significant. A clever landlord might instruct employees to review the algorithm’s output and manually adjust prices, adding a layer of supposed randomness to obfuscate the algorithm’s influence. Or they could simply pay a person to collate data and then adjust prices based on that. This would effectively render the ban useless.

The focus on AI algorithms seems to miss the larger picture. The real issue lies in a market where there is a vast imbalance between supply and demand, combined with an absence of sufficient rent regulation. While curbing collusion is important, addressing the systemic problems related to scarcity and market manipulation requires a more holistic approach that goes beyond simply banning algorithms. Even if the algorithms were banned, the underlying issues of scarcity and market mechanisms would remain.

The underlying issue appears to be the combination of scarcity and the market structure. The scarcity of housing contributes greatly to price increases, and the current market structure allows a small group of people and/or companies to dominate the market, creating a situation where price manipulation is easy. A combination of market manipulation, and not enough housing is the problem. There is insufficient regulation in place to combat this imbalance.

In short, while the intent behind San Diego’s ban on landlords using algorithms for price-setting is understandable, the ordinance’s practical enforcement and its potential impact on the overall housing market raise serious questions. Addressing the deep-seated issues of housing scarcity and market manipulation through a more comprehensive approach, rather than focusing solely on the algorithmic tool used, seems a more promising strategy for tackling the problem of unaffordable rent. The core issue is not the algorithm itself, but rather the lack of effective rent control and the limited supply of housing options. Therefore, any solution must also address these underlying factors.