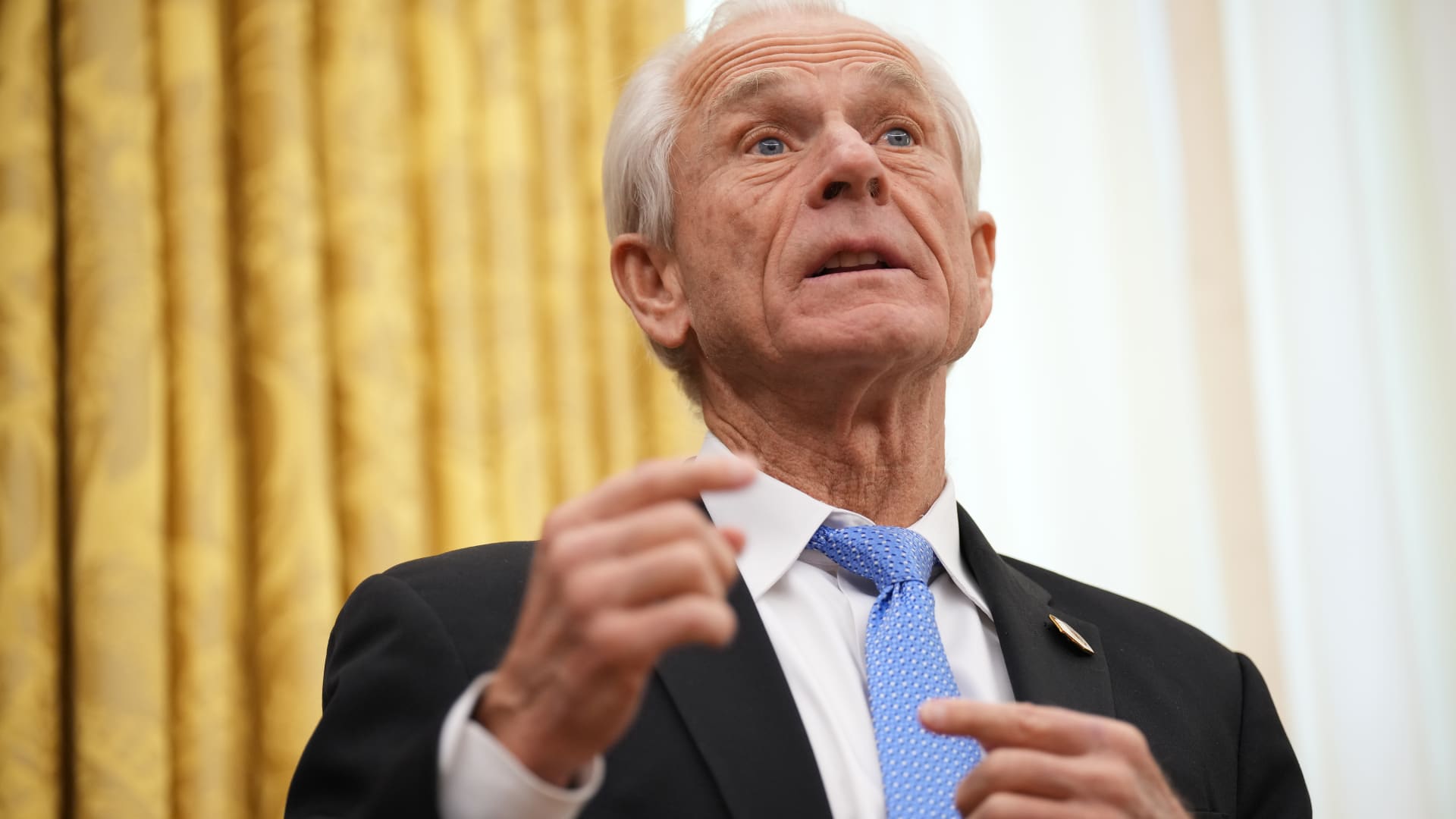

Despite Vietnam’s offer to eliminate tariffs on U.S. imports, White House trade advisor Peter Navarro stated this would be insufficient to lift recently imposed levies. Navarro cited concerns over non-tariff barriers, including the rerouting of Chinese goods, intellectual property theft, and Vietnam’s value-added tax, as key obstacles. He later clarified that the zero-tariff offer would be a “small first start,” but significant trade issues remain. These tariffs, announced by President Trump, caused a stock market downturn, and further negotiations are anticipated.

Read the original article here

Peter Navarro’s assertion that Vietnam’s 0% tariff offer is insufficient highlights a deeper issue: the focus on non-tariff barriers. He argues that even eliminating tariffs wouldn’t address what he perceives as unfair trade practices. This perspective suggests a belief that trade deficits are inherently negative and require a more forceful approach than simply lowering tariffs.

This focus on non-tariff barriers shifts the discussion away from traditional trade negotiations. Instead of focusing on the explicit costs of tariffs, the emphasis moves to regulations, subsidies, and other less visible aspects of international commerce. This perspective implies that these less visible elements are being manipulated to create an uneven playing field.

The claim that Vietnam’s 0% tariff isn’t enough suggests a broader dissatisfaction with the current state of trade relations. It implies a need for more fundamental changes to how trade is conducted. It’s not simply about the price of goods but about the overall structure and fairness of the agreements.

This viewpoint casts trade deficits as a sign of unfair practices, rather than a natural outcome of different economic structures and consumer preferences. It implies a belief that countries are actively manipulating trade rules to gain an advantage, a viewpoint that may be overly simplistic.

The assertion that “it’s the non-tariff cheating that matters” suggests a desire for a greater level of control over international trade. This might include stricter enforcement of existing regulations or even the imposition of new ones. It represents a rejection of free-market principles in favor of a more interventionist approach.

This perspective raises questions about the practical challenges of addressing non-tariff barriers. Identifying and quantifying such barriers is far more difficult than simply examining tariff rates. It also necessitates international cooperation and agreement, which can be challenging to achieve.

The overall implication of this statement is a desire for a more aggressive and protectionist trade policy. It suggests a willingness to use trade as a tool to achieve other geopolitical goals, potentially at the expense of economic efficiency. This aggressive stance is not solely focused on tariffs but on a wider range of trade practices.

This approach to trade negotiations may lead to unpredictable outcomes. The lack of clarity regarding specific goals and the reliance on broad accusations of “cheating” make it difficult for other countries to engage in meaningful negotiations. Such a strategy may lead to further instability and reduced global cooperation.

The perception that trade deficits are inherently negative, independent of other economic factors, is a flawed premise. Trade deficits are not necessarily an indicator of exploitation or unfair practices. Instead, they often reflect factors such as consumer preferences and exchange rates.

Moreover, the proposed focus on non-tariff barriers presents a significant challenge in terms of implementation. Pinpointing and addressing specific non-tariff issues requires detailed economic analysis and international collaboration, which may be difficult to achieve in the current political climate.

In summary, the claim that Vietnam’s tariff offer is inadequate because of “non-tariff cheating” represents a shift away from traditional trade negotiations. It reflects a broader, more protectionist and interventionist approach to international commerce, raising concerns about the potential for conflict and economic instability. Such a strategy runs the risk of hindering global trade and economic growth. The focus on undefined “cheating” provides little basis for constructive engagement with international partners.