Readers are encouraged to submit news tips to The Daily Beast. The submission process is streamlined for ease of contribution. This allows readers to actively participate in journalistic endeavors. All tips will be considered and investigated. Help shape the news by sharing your information.

Read the original article here

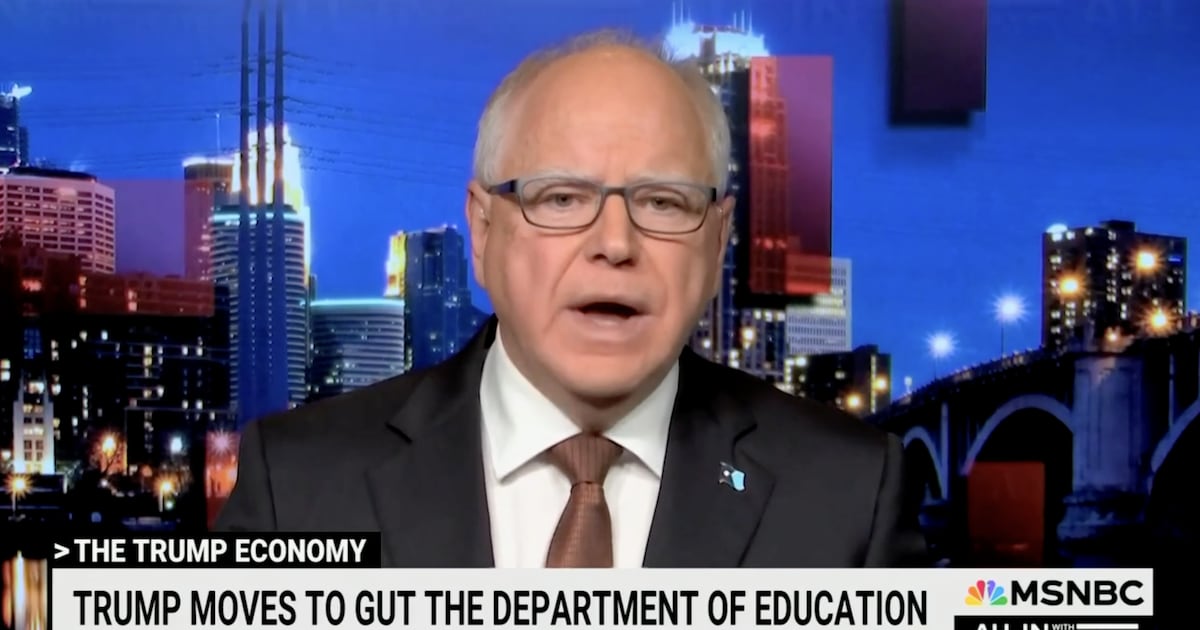

Tim Walz’s statement, “I own this,” regarding the outcome of the election and the subsequent political and economic turmoil, presents a fascinating case study in leadership and accountability. While his declaration of responsibility is commendable, a deeper look reveals a complex interplay of factors that extend far beyond the actions of a single campaign.

His willingness to accept a share of the blame for the campaign’s shortcomings, particularly the perceived fumbling of their closing argument, showcases a refreshing honesty often lacking in political discourse. This suggests a leader who prioritizes self-reflection and a desire for improvement, qualities undeniably valuable in public service.

However, assigning sole responsibility for the widespread consequences of the Trump presidency to the Walz/Harris campaign risks oversimplifying a deeply rooted issue. The election’s outcome was shaped by a multitude of factors, including widespread disinformation campaigns, the influence of partisan media, and the deeply entrenched divisions within the electorate.

The argument that the campaign should not have had to rely on a compelling closing argument because of the apparent flaws of the opposing candidate is compelling. Indeed, the opponent’s alleged actions and public image might seem to present a near-unbeatable position. But ultimately, elections are decided by voters, and the campaign’s failure to connect with enough of them remains a key factor.

It is crucial to recognize the significant influence of factors beyond the control of any single campaign. The American electorate’s choices played a defining role. Many voters’ actions reflected deep-seated biases and beliefs, rather than a rational assessment of candidates’ platforms or qualifications.

While praising Walz’s accountability, many argue that the blame should be far more widely shared. The responsibility should fall on those who actively propagated misinformation, on those who supported candidates with deeply problematic pasts, and even on those who chose not to participate in the democratic process by abstaining from voting. A significant portion of the blame undeniably rests upon the voters themselves.

There’s a crucial point about the electorate’s role. It highlights a fundamental problem in American politics: the influence of misinformation, the polarization of the electorate, and the declining civic engagement of many citizens. The lack of informed participation in democratic processes ultimately contributed to the outcome, and its consequences extend far beyond the realm of a single election.

Nevertheless, Walz’s willingness to accept responsibility, while possibly misguided in terms of its scope, underscores the importance of leadership that prioritizes accountability, even when circumstances may appear unfavorable. This kind of transparency fosters trust and encourages a more productive national dialogue, focusing on the necessary improvements in how political discourse and democratic processes function. It is a quality that should be valued highly in political figures, regardless of whether they ultimately bear the greatest responsibility for the outcome.

In the end, Walz’s “I own this” is a complex statement, inviting a broader discussion about the responsibility of candidates, the role of the electorate, and the overall state of American democracy. The statement itself acts as a catalyst for examining multiple dimensions of culpability and fostering a deeper understanding of the factors that shape election outcomes and their ramifications. The issue isn’t solely about who is to blame, but rather, how to prevent similar situations from occurring in the future.