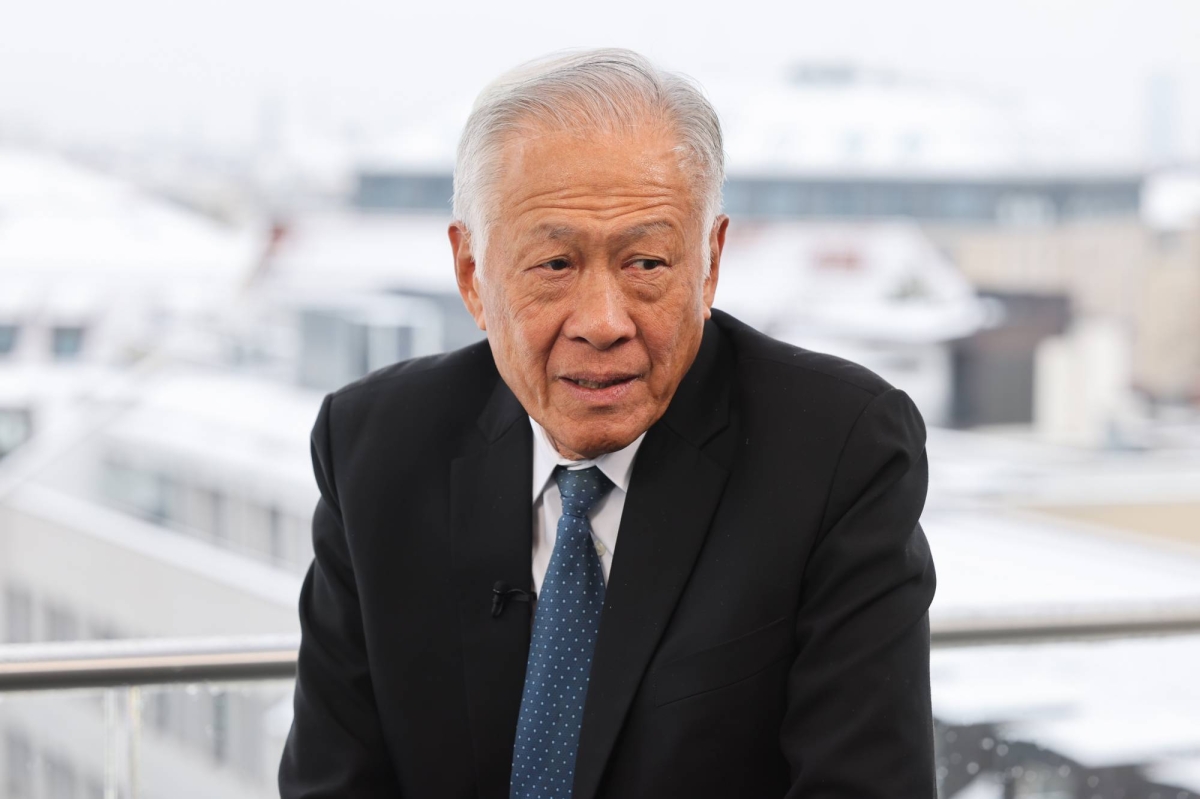

In a shift from its post-World War II image, the United States is now viewed by some in Asia less as a moral force and more as a self-interested power. This change, highlighted by Singapore’s defense chief Ng Eng Hen at the Munich Security Conference, reflects a fundamental alteration in perceptions since the Kennedy era. The U.S. is now seen as a “landlord seeking rent,” rather than a liberator, contrasting sharply with its historical role. This altered perception stems from a reassessment of US actions and their impact on the region.

Read the original article here

Singapore’s recent assertion that Asia now perceives the United States as a “landlord seeking rent” is a potent metaphor reflecting a significant shift in international relations. This perception isn’t simply about financial transactions; it encapsulates a deeper disillusionment with the US’s role on the world stage. The shift from a perceived era of goodwill and collaborative engagement to one characterized by transactional relationships and perceived threats has left many feeling betrayed and resentful.

The image of a “landlord” demanding payment, or worse, a “slumlord” threatening eviction, aptly describes the feeling that many nations now harbor towards the United States. This sentiment suggests a move away from the collaborative partnerships that once defined US foreign policy towards a transactional approach that prioritizes immediate self-interest. This shift is seen by some as a fundamental betrayal of previously established trust, leading to the erosion of decades of soft power.

This perception isn’t simply the result of a recent change in leadership. While the current administration’s policies may have exacerbated the issue, making the transactional nature of their approach far more explicit, the underlying shift towards a transactional foreign policy is far more fundamental. Decades of diplomatic efforts to build alliances and promote cooperation have been overshadowed by a growing sense that the US’s engagement is primarily driven by its own economic and strategic interests. The feeling that the U.S. engages in an unbalanced exchange where benefits aren’t equally distributed fuels this resentment.

The feeling is that the US demands continued support, military access, and economic concessions, without reciprocating the same level of commitment and respect for the sovereignty of its partners. This is not a new problem, but it has been amplified recently by the overtly transactional approach taken by the current administration. This creates an imbalance of power, where less powerful nations feel forced to comply with US demands for fear of repercussions.

The comparison to a mafia boss extorting “protection money” is another evocative image. It highlights the fear that if nations don’t meet the U.S.’s demands, they will face negative consequences, emphasizing the coercive nature of the relationship. This perception threatens not only established relationships but also casts a shadow over future collaborations, making it increasingly difficult for the US to build and maintain trust with other countries.

The suggestion that the U.S. is “seeking rent on houses it doesn’t own” speaks to the growing perception that its influence is waning. The sheer number of US military bases overseas, once a symbol of its global dominance, is now viewed by some as a symbol of unwarranted encroachment. The prospect of a reduction in this footprint only underscores this concern. The question is raised whether the US still has the economic and military leverage to impose its will globally, as its actions have not been consistently effective in achieving its objectives.

Furthermore, the feeling that the US is increasingly prioritizing its own domestic concerns over its international commitments also contributes to this perception. This prioritization is felt to have resulted in a disregard for the concerns and needs of its allies, contributing to a sense of abandonment and fueling the resentment that now characterizes many international relationships. The previously dependable ally is now seen as an unreliable and self-serving partner, leading to a reevaluation of long-standing alliances.

This shift in perception raises serious concerns about the future of global stability. The loss of trust in the U.S. could lead to the fracturing of established alliances, creating power vacuums that authoritarian regimes might seek to fill. The previously unquestioned position of the U.S. as a global leader is being challenged, making the future of international relations uncertain and potentially unstable. The implications of this shift for countries that once relied on the US for support are especially concerning. It opens the door to a new geopolitical landscape, one where multilateralism is threatened and where power dynamics are in flux. The question now becomes, how will the US respond to this changing perception, and what will be the consequences of its response?