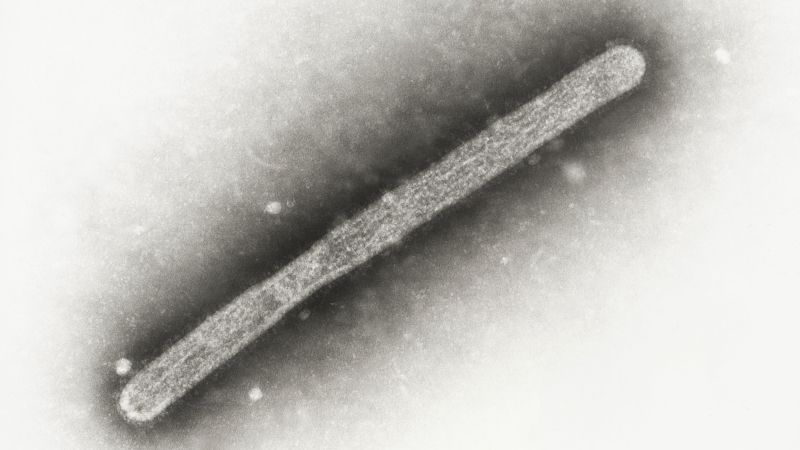

A new avian influenza variant (H5N1 D1.1) has infected dairy cattle in Nevada, exhibiting a mutation enabling more efficient replication in mammals. This mutation, unseen in other D1.1 strains, raises concerns about increased human transmission risk, particularly for those working with livestock. A farm worker has already tested positive for H5N1 in Nevada, displaying symptoms including conjunctivitis. The virus’s origin is currently under investigation, with theories suggesting transmission via wild birds or another intermediary animal.

Read the original article here

Bird flu, specifically a variant found in Nevada cows, is exhibiting concerning signs of adaptation to mammals. This development is alarming because it represents a potential leap in the virus’s ability to infect and spread among humans. The strain identified, 2.3.4.4b (B3.13), acts as an intermediate between strictly avian and strictly mammalian influenza viruses. While currently showing a preference for avian-type receptors, it demonstrably *can* infect via human-type receptors. This dual capability is unusual and significantly raises the risk of further mutation and adaptation.

The fact that this strain is already infecting cows, a mammal, is inherently worrying. Cows represent a significant intermediary host. The potential for widespread transmission within the densely populated livestock industry is substantial. The sheer scale of industrialized agriculture, with animals often kept in close proximity under potentially unsanitary conditions, creates a perfect breeding ground for rapid viral spread and evolution. This high-density environment significantly increases the risk of further mutation and the potential for more dangerous strains to emerge.

Adding to the concern is the simultaneous presence of another strain, 2.3.4.4b (D1.1), in wild birds. This strain has already been linked to severe illness and even death in humans. Should these two strains co-infect a cow, or even a human, the potential for genetic reassortment is extremely high. This process, called antigenic shift, could lead to entirely new viral variants. Such variants could combine the pathogenicity (disease-causing ability) of the deadly D1.1 strain with the mammal-infecting capability of B3.13. The resulting virus could prove far more transmissible and virulent in humans.

The segmented nature of the influenza A virus genome allows for this rapid evolution. The potential for a new, highly pathogenic pandemic strain combining with existing seasonal flu is a very real threat. While there’s a possibility this could all “blow over,” the risks are simply too significant to ignore or downplay. The potential for a new pandemic, particularly given existing political and societal factors, is a sobering reality.

The existing bird flu vaccine provides a crucial starting point, but ramping up production and ensuring widespread vaccination would be crucial in a significant outbreak scenario. However, historical vaccination rates against other diseases raise concerns about the potential challenges in achieving sufficiently high immunization levels across the population. Public health infrastructure is essential, yet current discussions surrounding healthcare funding and resource allocation raise serious questions.

Beyond vaccination, preventative measures are key. These include basic hygiene practices such as diligent hand washing and sanitization, as well as masking in public settings. Avoiding raw dairy and poultry products is a wise precaution given the known transmission pathways. Maintaining awareness of the situation and staying informed through credible news sources is also crucial. Advocating for improved biosecurity measures in both the agricultural and wildlife sectors is vital.

The situation underscores the importance of continued research into influenza viruses, improved surveillance systems, and rapid response capabilities. The potential consequences of underestimating or ignoring this threat are immense. This emphasizes the crucial role of effective public health systems and collaborative international efforts to mitigate such risks. The interconnectedness of the global food supply and wildlife populations highlights the need for a proactive and globally coordinated approach. The time for complacency is long past.

The situation warrants serious attention and proactive measures to prevent a potential widespread outbreak. Ignoring the problem or prioritizing economic concerns over public health carries unacceptable risks. The future health and safety of populations worldwide hinge on a swift and coordinated response to this emerging threat. This includes not only medical interventions, but also addressing the underlying societal factors that can either facilitate or hinder effective pandemic preparedness and response.