Following 150 days of imprisonment in Greenland on an Interpol red notice issued by Japan, Paul Watson was released after Denmark rejected Japan’s extradition request. The Danish justice minister cited insufficient assurances from Japan that Watson’s pre-trial detention would be credited towards any future sentence. Watson, a prominent anti-whaling activist, faces charges related to a 2010 incident involving a Japanese whaling ship, but maintains his innocence. His release allows him to reunite with his young sons for Christmas.

Read the original article here

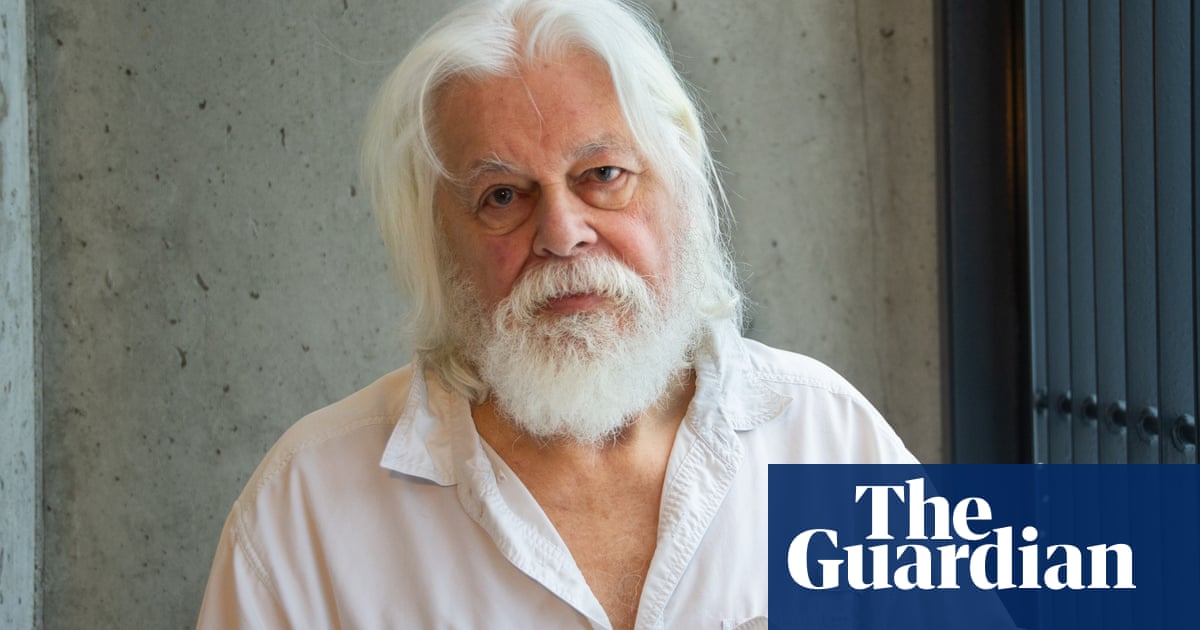

Paul Watson, the renowned anti-whaling activist, recently celebrated his release from a Danish jail after Denmark refused Japan’s extradition request. His relief is palpable, given his prior statement that he didn’t believe he’d survive a Japanese prison sentence. This fear wasn’t simply dramatic hyperbole; there’s considerable evidence suggesting his apprehension was well-founded.

The Japanese prison system, unlike many Western models focused on rehabilitation, is notoriously harsh and unforgiving. It operates with an almost military-like rigidity, controlling every aspect of a prisoner’s life, from sleep posture to the minutest daily actions. Even minor infractions can lead to severe punishments, including beatings and strangulation. This highly structured, unforgiving environment would be especially challenging for someone like Watson, accustomed to a very different lifestyle and culture.

His age further complicated matters. At 74, facing a potential 15-year sentence, the likelihood of him dying in prison before completing his term was very real. This isn’t simply a matter of his age impacting his ability to endure the rigors of imprisonment; the harsh conditions of Japanese prisons would drastically accelerate the deterioration of his health. He wasn’t exaggerating when he expressed concern about not returning home.

Further fueling his anxieties are the experiences of others. Anecdotal accounts highlight the Japanese system’s tendency to manipulate evidence and even make prisoners “disappear.” Considering Watson’s prominent role in exposing Japan’s illegal and brutal whaling practices, it’s unsurprising that he found himself targeted by a system notorious for its high conviction rate. This high rate, often touted as a sign of efficiency, is also interpreted by many as a sign that due process and fairness aren’t always guaranteed. Many believe a 97% conviction rate isn’t achievable without some level of manipulation or fudging of evidence.

While some argue his statement of “I’m not coming home” is an overreaction—claiming that after serving a sentence he would be released—the reality is his age and health made this a legitimate fear. His time would be spent in an extremely demanding and unforgiving environment. It’s easy to see why he felt his chances of survival in a Japanese prison were slim.

It’s important to remember the context of Watson’s activism. He’s a long-time opponent of Japanese whaling, famously confronting their whaling fleets for decades. His actions, often controversial, are born from a strong belief in the need to protect whales and other marine animals from unsustainable and inhumane practices. While some label him an “eco-terrorist” for his aggressive tactics, his methods are driven by a deeply held commitment to conservation.

It is worth remembering that Watson was not only a significant figure in environmental activism. He was a founding member of Greenpeace, later parting ways to establish the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, where he continued his crusade against whaling and other harmful practices. While his actions might be considered extreme by some, his dedication and bravery cannot be denied. He risked his life and freedom to defend his beliefs.

Denmark’s decision to deny Japan’s extradition request was widely celebrated, seen as a victory not only for Watson, but for the cause of marine conservation. This decision highlights a growing global awareness of Japan’s whaling practices. Regardless of individual opinions on Watson’s methods, it’s impossible to ignore the moral and ethical questions raised by Japan’s actions and the conditions within their penal system. The sheer relief at his release underscores the deep-seated fear, not just of imprisonment, but of the potential for irreversible harm within the Japanese justice system. Ultimately, Watson’s case highlights the intense clash between environmental activism and the practices of a nation fiercely protective of its whaling industry.