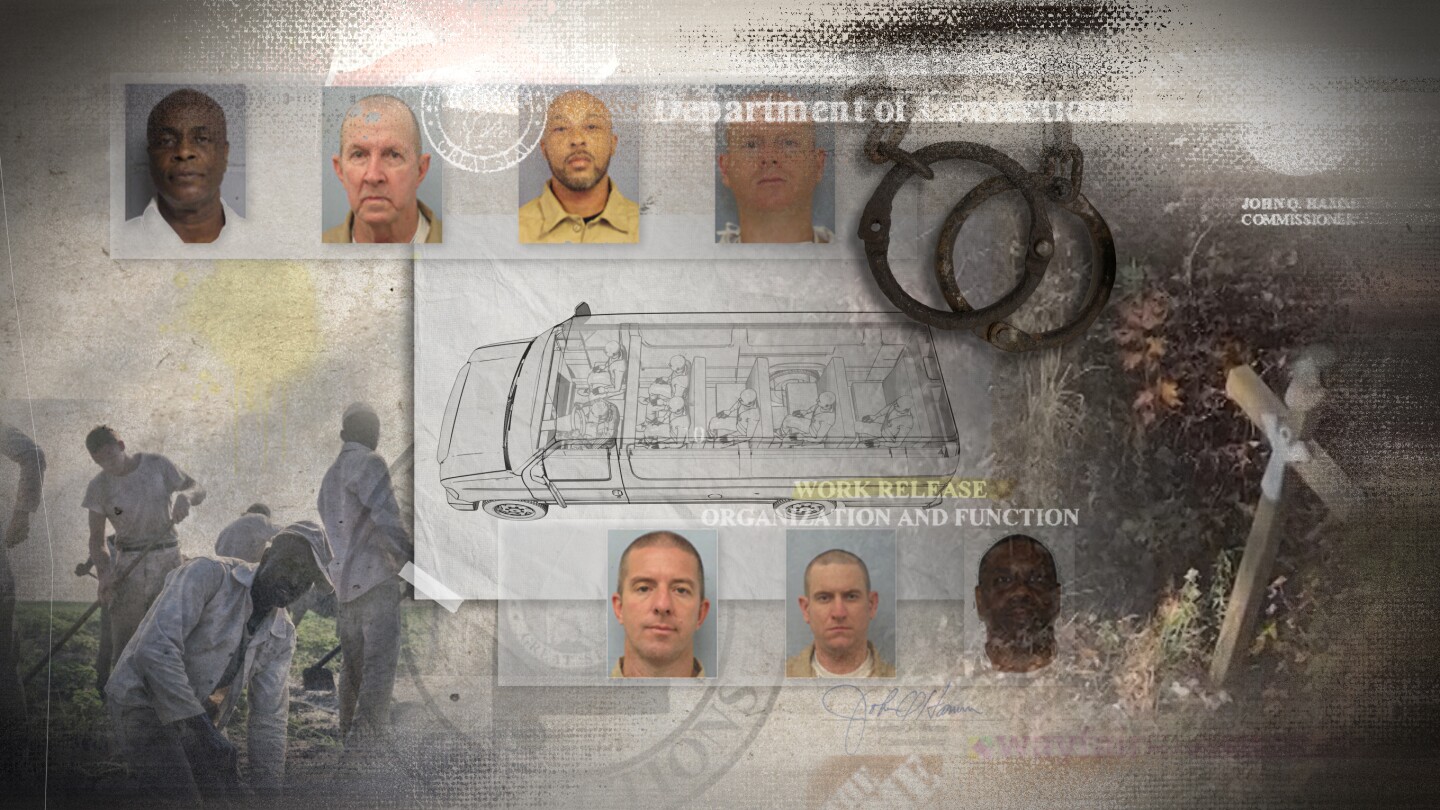

A deadly van crash in Alabama, involving a work-release inmate driving six other prisoners, highlights the state’s extensive and controversial use of prison labor. The driver, with a history of escape and failed drug tests, was unsupervised and responsible for transporting inmates to jobs at private companies like Home Depot and Wayfair. Two prisoners died in the crash, raising concerns about the safety and ethical implications of Alabama’s profit-driven system of contracting out prison labor. This system, with roots in the convict leasing era, generates millions for the state while inmates face harsh conditions and low pay, often with little oversight. The incident underscores the broader issues of forced labor and exploitation within Alabama’s prisons.

Read the original article here

Alabama’s prison system presents a stark and unsettling paradox: it profits handsomely from the labor of incarcerated individuals working in businesses like McDonald’s, yet simultaneously deems these same individuals too dangerous for parole. This juxtaposition reveals a deeply troubling system that appears to exploit vulnerable populations for financial gain, while simultaneously perpetuating a cycle of incarceration.

The state’s long and problematic history of using prison labor, dating back over 150 years and even rooted in the convict leasing system that followed the abolition of slavery, highlights a continuous pattern of utilizing incarcerated individuals as a cheap and readily available workforce. This practice, which has generated hundreds of millions of dollars for the state, raises serious ethical questions about the fundamental principles of justice and rehabilitation. The system generates significant revenue not only through direct payment for prison labor but also through considerable cost savings achieved by avoiding the hiring of civilian workers for various governmental tasks.

Many jobs are located within prison walls, but thousands of inmates are also employed in outside facilities, contributing millions of hours annually to various private sector enterprises, ranging from major corporations to smaller local businesses. This widespread use of incarcerated labor raises concerns about worker exploitation and fairness. While some argue that these outside jobs offer a benefit to prisoners by providing a respite from the often-violent conditions inside, this hardly mitigates the inherent ethical concerns. The crucial point is that these workers are not paid fairly, they lack the choice to work without facing repercussions, and they are denied the same basic workplace rights afforded to all other Americans. This points toward a system that prioritizes profit over the human rights and dignity of its prisoners.

The sheer scale of the problem is striking. Millions of dollars are generated through “work release fees” alone, with some estimates suggesting that the overall financial benefits to the state from prison labor are vastly higher, encompassing considerable savings in operating costs. This financial incentive appears to significantly outweigh any genuine consideration of rehabilitation or reintegration into society.

The claim that these prisoners are deemed “too dangerous for parole” while simultaneously considered safe enough to work in public-facing roles highlights a significant hypocrisy within the system. This contradiction raises questions about the true reasons behind the denial of parole; is it a matter of public safety, or is it merely a convenient justification to maintain a readily available and exploitable workforce? The argument that these jobs are “voluntary” rings hollow in the context of a system where prisoners face potential punishment for refusing to work and lack any meaningful bargaining power.

The parallel to historical systems of slavery is impossible to ignore. While the explicit language of slavery may not be present, the core dynamics—forced labor, minimal compensation, and the lack of basic human rights—are strikingly similar. This raises fundamental questions about the interpretation and application of the Thirteenth Amendment, which ostensibly abolished slavery except as punishment for a crime. This exception has been interpreted broadly, and its use in the current context clearly needs a critical reevaluation.

Furthermore, the disproportionate representation of Black individuals within Alabama’s prison system adds another layer of complexity to this issue, suggesting that systemic racism may play a significant role in both incarceration rates and the subsequent exploitation of prison labor.

In conclusion, the practice of profiting from prison labor while simultaneously denying parole to the same individuals highlights a profound ethical failure. This is not simply a matter of economic policy; it is a matter of human rights and social justice. A thorough reform is needed to address the systemic issues driving this exploitation, ensuring that fair wages, meaningful choices, and basic worker protections are extended to all, regardless of their incarceration status. The current situation, however profitable for the state, reveals a deeply flawed and unjust system that necessitates fundamental change.