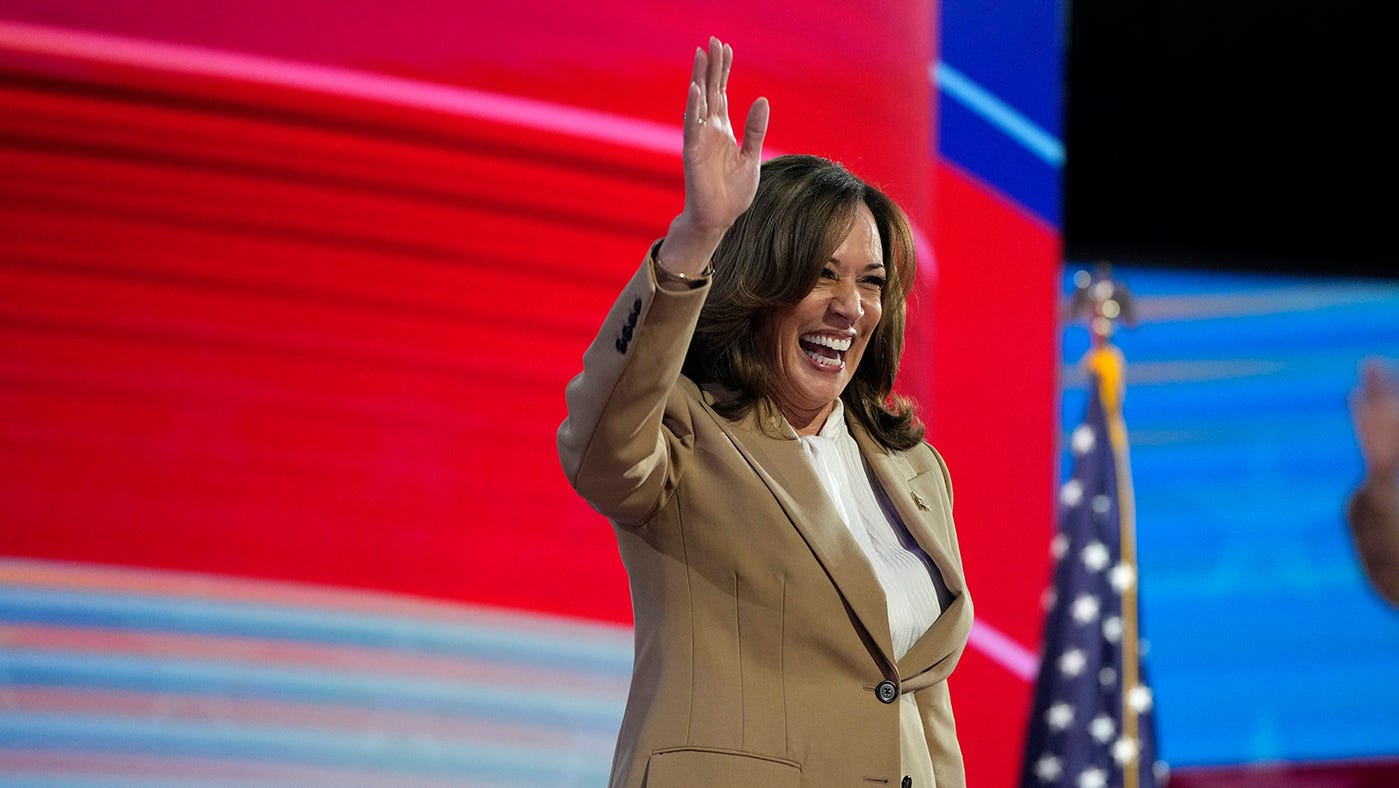

Jerry Preston argues that Donald Trump’s electoral success against female candidates Hillary Clinton and Kamala Harris, both of whom received roughly 227 electoral votes, suggests a societal resistance to electing a woman president. He posits that this resistance mirrors similar biases against women in religious leadership roles. Preston concludes that while women have made significant progress, the US is currently not prepared to elect a female president. A rebuttal linked within the letter disputes the central claim, suggesting other factors contributed to Harris’s loss.

Read the original article here

Americans should admit that we rejected Kamala Harris because she’s a woman; this assertion, while seemingly simplistic, deserves a nuanced examination. Many factors contributed to her electoral performance, and reducing it solely to gender overlooks the complex tapestry of political realities.

However, to dismiss the role of gender entirely is to ignore a significant element within the broader context. The persistent presence of sexism in American politics cannot be ignored, and its influence on voter perceptions, whether conscious or unconscious, is undeniable. A woman, even a highly qualified one, faces unique challenges navigating a system historically dominated by men.

Furthermore, the narrative surrounding Kamala Harris’s candidacy frequently emphasized her identity before her policy positions. This disproportionate focus on her gender, rather than her qualifications and political platform, suggests a deeper societal bias at play. It’s not just about individual voters; the media landscape, political discourse, and even campaign strategies themselves often contributed to this narrative.

The argument that she was a “bad candidate” is itself often colored by this bias. What constitutes a “good” or “bad” candidate is subjective and shaped by expectations that often differ based on gender. A woman might be held to a higher standard of competence or perceived likability than a male counterpart, leading to harsher judgment.

It’s also important to acknowledge that the reasons for her lack of popularity were multifaceted. Her association with a beleaguered administration, the economic anxieties facing many Americans, and her struggles to connect with voters on key issues all played significant roles. These factors, however, cannot exist in a vacuum; they interacted with existing prejudices that impacted how voters perceived her.

Some argue the Democratic Party’s strategic choices contributed to her defeat. The late entry into the campaign, lack of a strong primary challenge, and limited time to build a robust grassroots movement all hampered her ability to gain traction. These strategic failures exacerbated the pre-existing challenges she faced as a woman candidate.

Dismissing the impact of gender as insignificant is not only inaccurate but also prevents meaningful self-reflection within the Democratic Party. The party needs to address the systemic issues that impact female candidates, as well as broader problems of voter engagement and messaging.

The claim that focusing solely on gender ignores other factors is true, but those other factors frequently operate within a framework shaped by gender dynamics. To fully understand the outcome of her candidacy, we must analyze the interplay of all these elements.

In conclusion, while attributing Kamala Harris’s electoral performance solely to her gender is an oversimplification, ignoring the role of sexism in American politics is equally misleading. A candid assessment requires acknowledging the multifaceted factors involved, including the persistent presence of gender bias, the party’s strategic choices, and the broader political and economic environment. Only through such a comprehensive analysis can the Democratic Party learn from the past and strive for a more inclusive and successful future.